In the Archives: Two Worlds

Editor’s note: The new University of Michigan North Quad residential hall, which is opening this fall at the corner of State and Huron, will house the Global Scholars Program among various other initiatives. The goal of the program is reflected in a quote from a participant: “I learned to understand differences as diversity, not strangeness.” Historically, that attitude did not always serve as this country’s educational approach to other cultures – as this edition of Laura Bien’s bi-weekly history column shows.

Eighteen-year-old George Moore boarded the eastbound train on a chill November day in 1898. Several of his schoolmates climbed on. The boys sat near Mrs. Lizzie McDonald, their guardian.

It would be a long journey.

Four days and three nights over the clacketing steel rails lay between his Idaho birthplace and a Pennsylvania boarding school.

Built in 1879, the Carlisle school was led by its founder Richard Henry Pratt, a former Civil War volunteer who after the war served as an officer in the 10th Cavalry. Its members included Buffalo Soldiers and Native American scouts. In western Indian Territory, Pratt’s group was in charge of enforcing reservation borders to protect settlers’ lands; Indians left the reservation to seek food.

Pratt was also put in charge of a group of Native American prisoners whom he treated humanely, comparatively speaking, even giving them sketch pads in which to draw their experiences. Years later in his book “Battlefield and Classroom,” Pratt wrote, “Talking with the Indians, I learned that most had received English education in home schools conducted by their tribal government. Their intelligence, civilization, and common sense was a revelation because I had concluded that as an Army officer I was there to deal with atrocious aborigines.”

However, in his later role as schoolmaster, he also said, “In Indian civilization I am a Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.” Pratt had firm beliefs about how and why to educate his Carlisle students. In his era, Pratt’s assimilationist ideas were progressive.

George Moore, who had taken the train and attended the Carlisle School, eventually returned part-way back west – to Ypsilanti.

Pennsylvania: Carlisle School

Carlisle’s main building was a tumbledown abandoned army barracks. The year it opened, students spent much of their time cleaning and repairing the buildings. The curriculum consisted of industrial arts training for the boys, domestic arts training for the girls, academic classes, and language classes – not all of the students could speak English. It was the nation’s first off-reservation boarding school. One scholar called Carlisle “the flagship of the American Assimilation Era’s education program.”

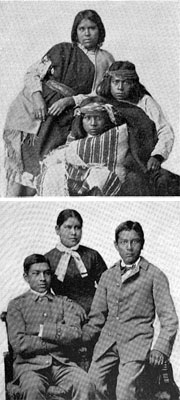

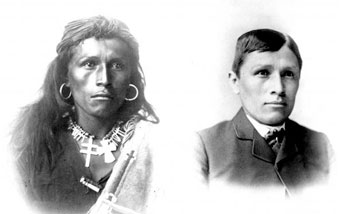

Top: Three students upon arrival to Carlisle Indian School. Bottom: The same students three years later.

George Moore arrived at Carlisle on November 21, 1898 and was placed in a boys’ dormitory. George was a full-blooded Nez Perce. The other students came from the Lakota, Oneida, Pueblo, Menominee, Shoshone, and numerous other Native American nations. The nation with the greatest number of representative students was the Iroquois; with the fewest, Klamath.

George could already read, write, and speak English. He’d previously studied at the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon. “George Moore” was not his real name, but likely the English name Chemawa had given him, as the school’s first enforced step to assimilation.

At Carlisle, the process of assimilation was enforced without accommodating the students’ diverse customs, beliefs, and cultures. As one small example, male students who had not previously attended a school such as Chemawa upon arrival received haircuts. This act deeply distressed those students for whom hair was cut only when a relative died.

Carlisle taught students ranging from grade school to high school age. George was placed at the high school freshman level. He made it to sophomore year and in addition to his academic subjects and industrial arts classes, began to learn how to play the oboe. The May 5, 1899 Indian Helper school newspaper said of one concert, “Thomas Morgan and Ralph King gave Saxophone solos, in a manner that pleased all, and Geo. Moore who plays the Oboe, made some merriment with tones on his new and peculiar instrument.”

As a junior, George attended two summer “Outings.” Carlisle’s “outing” program consisted of placing students in local homes to work and become more Americanized. The school deposited their earnings, however meager, in individual student accounts. George worked for a week in early June in Rushland, Pennsylvania, and then switched for a two-month stint in Langhorne.

George was slated for a five-year program at Carlisle and scheduled to graduate in late spring of 1902. He did not graduate. Most Carlisle students did not; historians estimate that only about one in eight students did.

Ypsilanti: Normal College News

However by October, George was a student at Ypsilanti’s State Normal School, taking a business course. He occasionally may have read the school’s newspaper.

Around this time the Normal College News ran an article written by Normal alum and former Ingham County resident Mary Fanson Lawrence. Mary graduated in 1887 and taught Latin and German in Aurelius, a town just south of Lansing. She married Glen Lawrence and the two traveled West, to a small day school at the base of one of the three mesas in the Moqui (Hopi) Reservation in Arizona. Glen taught a class of about 45 Hopi per day in Polacca school.

Though some women worked at two larger schools elsewhere on the reservation, Mary worked as a housekeeper. In 1901, Glen earned 72 dollars a month [$1,830 today] and she earned $30 [$763]. Their combined salaries had the modern-day value of $31,000 per year. Mary composed an essay about her life in Arizona, “Life Among the Indians of the Southwest.” She sent it to her alma mater.

“Friends have written, ‘In what part of Arizona is your town? We cannot find it on any map!’” reported her May 28, 1904 Normal College News article. “ . . . The traveler leaves the Santa Fe R. R. for the Moki Reservation . . . the villages are from 65 to 75 miles north, and about 100 miles from the Utah line. The journey takes one across the Painted Desert and seemingly endless stretches of sand, past great buttes, and around or over mesas, until the weary traveler is awed by the vastness of the desert . . .”

Mary continued, “The towns are seven in number, three of the villages being built upon an almost perpendicular rocky mesa, 6000 feet above the plain. It is known as the First Mesa . . . The villages were built on the high mesas so the Hopi could protect themselves when attacked by the Navajos. The houses are built side by side, like modern flats, of stone; and are from one to three stories high, built in terrace fashion, and entered by ladders on the outside; the roof of one room on the ground will be the front steps or yards of the next story, and so on. The rooms are low and we have to stoop to get around in them. The streets are narrow alleys, and the tourist has to pick his way among burros, chickens, dogs, and turkeys.”

Mary went on to say that some of the students had never attended school. “Of course, as they do not know a word of English when they enter school, and in looks and attainments are mere animals, the progress is necessarily very slow. When a child comes to us we give it an English name, as life is too short to spend in learning and pronouncing such names as Tuvayhongeva, Inowanghoeonsa, or Musaquaptewa.”

The curriculum included Christian instruction. “At Christmas time,” said Mary, “one of our large boys was helping to carry some pies which were being made for their dinner. He began singing, ‘In the Sweet Pie and Pie,’ entirely unconscious of any parody.”

Mary’s essay did not describe the Hopi perspective or belief system. It described such outward appearances as clothing styles and marriage customs. She likely did not know that the reservation’s village of Oraibi was and is one of the oldest continuously occupied settlements on the North American continent, founded before the year 1100.

Mary expressed irritation with other non-Native visitors who disagreed with the school’s mission. “There are many interesting things about these people, and they are visited frequently by sight-seers, ethnologists, and tourists, who are often a hindrance to us in our work, because they want this region to remain a show ground for the future, and talk or use their influence against any change or progress.”

Mary concluded her essay with the remark, “The Hopis are good-natured, light-hearted children, easily led in the wrong way by presents of candy and tobacco. Like children they need disciplining, and do not always regard those whose duty it is as their best friends.”

Coda

The fate of George Moore after his study in Ypsilanti is unknown to the writer. According to Barbara Landis, the Carlisle Indian School biographer for the Cumberland County Historical Society, a note in his onetime school file says that he died sometime before 1918, in his late 30s.

Mary Lawrence died in 1935 around age 72. She and Glen are buried in Maple Grove Cemetery in Ingham County.

On the Hopi reservation, Polacca Day School, the onetime home of Normal graduate Mary Lawrence and her husband Glen, was replaced in 2004 by a new K-6 elementary named First Mesa Elementary School.

The $20 million project, funded mostly with monies from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, was managed by the Hopi Tribe. The building was designed to reflect Hopi culture. Plans were drawn by Dyron Murphy Architects, a Native American-owned architectural firm.

Natural light fills the school, plumbing is super-efficient, no potable water is used for the xeriscaped grounds’ drip-irrigation system, and the structure is designed to minimize heat absorption.

The school reflects Hopi culture and ecological values, which survived the age of assimilation, in a high-tech modern manner: First Mesa Elementary is the first LEED-certified school in Arizona.

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

Last column’s Mystery Artifact elicited some guesses that included sandwich toaster, ashes shovel, and catfish scoop. Here’s what the museum tag says:

Brick baking oven shovel used in the family of George W. Kishlar’s father in 1820 and brought to Michigan by George W. Kishlar of Ypsilanti, who presented it for this collection.

This week’s artifact is an item from deep within a certain file within the Ypsilanti Archives. Can you guess its function? Good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

It appears to be some sort of ribbon for formal wear. The text translates to “German Workers Support Society”. This would probably have been a society similar to Ann Arbor’s Schwabischer Unterstuetzungs Verein (see [link] ).

Interesting guess cmadler. :)

I’m guessing the ribbon was worn on a uniform of some kind, during the German Workers Club “parades”. Most likely, held annually in Ypsilanti, during the late 1800′s.

Could it be a ribbon recognizing German Americans for their help in the civilian war effort during WWII? Those are the colors of the US, not Germany. And the handshake could be for a job well done.

Interesting guess, abc…hmmm.

The article doesn’t indicate the size of this object. I view it as a banner used by the German Society of Workers during their meetings. The joined hands indicates solidarity & support.

Irene Hieber

Oops, you are right, Irene; I should have scanned it with a ruler to indicate length. It’s roughly six inches long and about 2 3/4 inches wide.