In the Archives: Papered-Over Money Issues

Editor’s note: As municipalities in the state of Michigan start to look ahead to their next budget year, we will likely hear often about the difficult economic times in which we live – and the importance of squeezing every last dime out of the budget. It’s fair to guess, however, that wrangling over Michigan municipal budgets will not include a discussion of who should pay for toilet paper. There was a time, however, when the topic of toilet paper was fair game.

It is wise to choose one’s battles. For one hard-headed 1920 Ypsilanti alderman, the hill he chose to die on was a hill of toilet paper.

In that time, the city was halfway between old-timey days and the modern age. Fewer than a third of its 7,400 residents had telephones. The Ypsi phone directory was nine pages long. Due to a limited supply of electricity, many city factories deferred working hours to the night time. And an ongoing “sanitary sewer” project, viewed as a progressive upgrade from noisome urban septic tanks and privies, emptied directly into the Huron River.

Issues before the city council reflected this time of transition. At its Oct. 4, 1920 meeting, the council weighed the street commissioner’s bill for oats for his horse. The bill had been carried over from a previous council meeting when aldermen had struggled but failed to resolve the issue of a horse’s feed.

One alderman was fed up. “Alderman Worden said he had bought oats about the same time for 85 cents a bushel, while the charge for oats in this bill was $1.35,” reported the Oct. 5, 1920 Daily Ypsilanti-Press.

“Profound silence on the part of the other aldermen.

“Finally it was moved that the bill be paid, and the vote was 9 to 1 in favor.”

Local gardener Frank P. Worden did not approve. A veteran city office-holder and recent candidate for mayor, he took a dim view of those who sought political perks. When, at the same council meeting, the Third Ward election inspectors submitted a bill for election-day refreshments, Worden bristled.

“The amount involved was $2.35 [the equivalent of $25 today] – just the kind of bill that the council had heretofore paid without a murmur,” noted the local paper. “But this particular bill was strenuously objected to by Alderman Worden: ‘The inspectors get $10 [$106] a day; let them pay for their own lunches,’ he said.” The other aldermen conceded, and voted it down.

Another bill was submitted for $500 [$5,300] of park improvements despite an emptied parks fund, said the paper. “‘When a fund is exhausted how can a bill be paid?’ asked Alderman Worden. ‘Nobody has any authority in the charter to pay such a bill.’” His colleagues disagreed and approved the expense.

Worden had been overridden on the questions of parks and oats. He wasn’t pleased. The next bill before council kicked off a two-month saga, led by Worden, that involved one of the city’s most popular and prestigious charities.

Members of the Patriotic Service League included many of the city’s most prominent citizens. The group raised money for wartime charity drives and opened a downtown employment office for returning World War soldiers. The P.S.L. raised funds for the erection of a war memorial plaque, visible today on the southwest side of Cross Street Bridge.

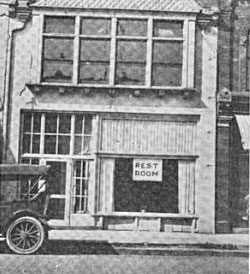

The P.S.L. also sought to refine civic life. In the spring of 1919, the group opened a municipal “Rest Room” at 29 North Huron, on the west side of the street just north of Michigan Avenue. The two-story facility offered an elegant yet comfortable parlor with easy chairs, tables of magazines to peruse, a telephone, and a writing desk with complimentary stationery. Another room contained a fainting couch and basic medical supplies. The Rest Room also had several conference rooms and large and elegant bathrooms. An on-site matron presided over the Rest Room and welcomed downtown shoppers wearied from their labors.

The P.S.L. had originally split the cost of the Rest Room with the city, with the agreement that after a year, the city would assume all expenses. The city had a different understanding, claiming that the 50-50 split was permanent, and it had based that year’s budget on that understanding. At the Oct. 4 council meeting, former mayor Lee Brown spoke up for the P.S.L., lauding its work and claiming that the city should henceforth pay the total cost of the Rest Room. Dissent arose. “[S]omething like 15 minutes were occupied in hearing objections to paying incidental bills connected with the Rest Room, of which toilet paper was an item,” said the paper. The issue was tabled.

At the next council meeting on October 18, the battle continued. “Just who will pay for the toilet paper for the Rest Room is still undecided,” wrote the Press. “‘I don’t see how the city can pay for the Rest Room,’ said Alderman Worden [that] night to Mrs. Brown and Mrs. Quirk, who represented the Patriotic Service League and brought the minutes of their organization with them to show that they had not promised to help support the Rest Room this year, though they had set aside $300 for that purpose.”

Worden did not back down. By December, the issue still wasn’t settled. “What to do with the Rest Room again came before the council,” reported the Dec. 7 Press. “Unless some action is taken soon, the rest room will have to be closed up, for the appropriation is about exhausted.

“It was referred to the Rest Room Committee who will meet the officers of the Patriotic Service League and see if some plan cannot be evolved to keep the room open.”

The issue vanished from subsequent Council proceedings as reported in the paper, suggesting that the P.S.L. quietly yielded to the strictures of the Rest Room Committee. If so, Worden’s stubbornness had paid off.

But the Rest Room’s days were numbered. By 1927, it had moved across the street and designated some of its space as an office for city social worker Inez Graves. Shortly thereafter, the Rest Room closed. The local police force took over the spot as a downtown station.

Gone was the fatigued shopper’s elegant alighting-spot.

Mystery Artifact

Last column’s Mystery Artifact featured a moving part. Lisa Lemble and cmadler guessed correctly that this is a cherry pitter, with two curved claws to force out the pits.

This column’s artifact is also gustatory. This Ypsi-made item is one of several such objects at one time invented, patented, and produced in Ypsilanti. Many such devices could be found in 19th-century Ypsi and Ann Arbor homes.

But what is this approximately 12-by-8 inch vessel? Note: The cylinder assembly with a handle normally rests inside the potlike part at the bottom. Take your best guess and good luck!

It looks like an early version of a deep fryer. You put the base in the pot with oil and heat that up. You pop your marshmallows in the cylinder and immerse the cylinder in the oil on the base. You crank it to get an even brown. Voila, French fried marshmallows.

Mmmmm, deep-fried marshmallows, my favorite! :D Bonus: Atkins-friendly!

Just a W.A.G., but since it’s seasonal, I’ll guess that the mystery item might be a chestnut roaster. I don’t think I’ve actually ever had a roasted chestnut, but I would think that tumbling, to keep them evenly heated and avoid burning, would be important. This looks like it would do that nicely.

Philip P: You are very close! Also, some models of this object could treat 2 types of edibles.

“…2 types of edibles.” Really?

Chestnuts and marshmallows?

Laura,

I think it is a coffee bean roaster.

Irene Hieber