In the Archives: Edward Israel’s Polar Sky

Editor’s note: Now that we’ve settled into our season of cold, it’s fitting to remember that Michigan played a role in the polar exploration of the late 1800s.

In this week’s edition of her biweekly local history column, Laura Bien offers what could be considered a beautiful, if belated, obituary of Edward Israel, a University of Michigan student who perished on a polar expedition.

It was no surprise in the spring of 1881 when a University of Michigan senior was offered the prestigious post of astronomer on a federally-backed polar expedition.

Edward Israel was one of the brightest students in his class, and one of the youngest. He accepted. “The expedition will be absent two years,” reported the April 30, 1881 University of Michigan Chronicle, “so that Mr. Israel hopes to be present at the reunion of his class in ’84.”

He wasn’t.

Edward was the son of Kalamazoo’s Mannes and Tillie Israel. Born in Germany’s onetime duchy of Waldeck-Pyrmont, Mannes emigrated to America in 1841. In 1843 he arrived in Kalamazoo and opened an upscale dry goods store. It was so successful that he moved into larger quarters twice before constructing his own immense brick building on Main Street at Rose. “M. Israel & Co.” brought the Israels wealth and social prominence.

Largely self-educated, Mannes read voraciously. “He stored his mind with the thoughts of the best writers of the past and present,” said one biographer. “[H]is historical research was extensive, and he was remarkably well-informed upon the political history of Europe and America.” Mannes’s library at the family’s large, comfortable home on Burdick Street also contained volumes of poetry and tales of exploration.

Edward was born on July 1, 1859. He would grow up to have two elder siblings, Ann and Joseph, and three younger: Lillie, Gottwalt, and Mollie. Edward excelled at school, especially at math. He finished high school at age 16. The following fall, in 1877, Edward enrolled at UM. His father had been the first Jewish man to settle in Kalamazoo, and Edward was the only Jewish man in his class.

Edward was by now a handsome young man. He stood 5 feet 9 inches tall with a slender frame and dark hair. His brown eyes held a look of reflective reserve, and his manner was gentle and deliberate.

As in grade school, Edward distinguished himself as a brilliant student, at or near the top of his class. UM math professor Edward Olney regarded Edward as one of the best mathematicians he’d ever taught.

UM astronomy professor Mark Walrod Harrington said of Edward, “He read with me Watson’s Theoretical Astronomy, a work so advanced as to be beyond the range of most college students, and even to offer in places serious difficulties to the professional mathematician or astronomer.”

UM astronomy professor (and Observatory director) James Watson’s book included such chapters as “Investigation of the Differential Formulae Which Express the Relation Between the Geocentric or Heliocentric Places of a Heavenly Body and the Variations of the Elements of Its Orbit.” Continued Harrington, “Edward Israel not only read the entire book in a half year, but he seemed entirely unconscious that he was doing anything extraordinary.”

While Edward studied in Ann Arbor, Senator Omar Dwight Conger of Michigan introduced a bill in the U.S House of Representatives “to authorize and equip an expedition to the Arctic Seas.” It was the Lady Franklin Bay expedition led by Adolphus Greely. The expedition was not an anomaly; six other American federal polar expeditions were underway at the time. It was an era of polar romance and adventure – as well as horror and tragedy. Voyages made front-page news, and popular magazines published engravings of icebergs and auroral lights.

Conger’s bill passed. When it came time to assemble a crew, UM was solicited: did the faculty know of a good meteorologist-astronomer? Harrington recommended Israel, and the other faculty agreed.

Edward was thrilled and accepted. There was only one problem: to join the crew, he’d have to leave school before graduation. UM regents agreed to award him his degree in absentia. In April, Edward took leave of his professors and friends and went to Kalamazoo. After saying goodbye to his family he traveled to Washington D.C. and enlisted as a sergeant in the Signal Corps, then went to the expedition’s departure point, St. John’s, Newfoundland.

There, on June 29, 1881, Edward wrote a letter to his mother. “I was greatly surprised to-day on examining our supplies; there is nothing which could possibly be carried of which we have not a great abundance. As far as safety and comfort are concerned, no expedition was ever as well-equipped as ours.” The 22-year-old sailed on the 4th of July.

The expedition’s ship Proteus sailed north along Greenland’s western coast and battled pack ice in order to land at its destination, Ellesmere Island, on Aug. 13. Greely christened the place “Fort Conger” after the senator and the men built a barracks. The Proteus sailed away, scheduled to return in two years. At the 1-year mark, the relief ship Neptune was to resupply the party.

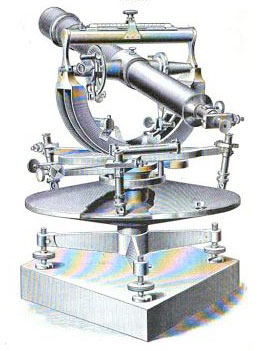

Edward faithfully took a range of daily measurements with his magnetometer, pendulum, theodolite, Perry transit, and sidereal chronometer. He slowly amassed immense tables of meteorological and astronomical data. In a later report, Greely wrote, “The records and computations made at Fort Conger by Sergeant Israel bear witness to his carefulness and conscientious performance of his duty.”

After one year, the Neptune failed to appear. At the two-year mark in the summer of 1883, the Proteus never arrived.

The men fled Fort Conger in five small boats through ice-choked seas. They headed for the southerly Cape Sabine and its food depot. Edward’s data and instruments, including his 100-pound pendulum, were on board. Edward took measurements from the boat to determine latitude, in trying to steer the party towards Cape Sabine. Unable to travel further due to ice, the men climbed onto a floe and drifted with the pack ice for 34 days, finally floundering onto the cape seven weeks after leaving Fort Conger.

There the party found two months’ worth of supplies cached. The eight months that followed rank among the most horrific experiences of polar starvation.

Edward's grave in Kalamazoo's Mountain Home Cemetery. Used with permission from photographer David Habben.

When the emergency rescue ships Thetis and Bear arrived on June 22, 1884, only seven of the original 25 crew members were alive. They were eating their shoes. Edward had died only twenty-six days earlier.

Later, it was said that of the bodies in shallow graves on Cape Sabine, Edward’s had been the only one not cannibalized.

When Edward’s body was returned to Kalamazoo on Aug. 11, city businesses closed. Thousands gathered at the train station. The mayor and city council attended Edward’s burial in the Jewish section of Mountain Home Cemetery. A weathered inscription on his stately grave seems to read “In Life a True Child of God/In Death a Hero.”

Perhaps his best memorial is from a moment of happiness at Fort Conger, when Edward observed a stunning aurora. He called Lieutenant Greely to see it too, who later described it with the words “graceful,” “intricate,” and “beautiful.” Edward’s description hewed more closely to scientific analysis, but one imagines this young man standing on the snow and gazing up, enraptured with delight and wonder.

“The finest display of colors was afforded by the spears of light and streamers darting downward from the auroral curtains. In these the colors were arranged in their spectroscopic order, and an observer, facing east, saw the red … on his right; violet on his left. The colors from green to violet were especially clear and brilliant. They were the last to appear and the first to disappear …”

Mystery Artifact

Last column, Chris, ABC, cmadler, Joan Lowenstein, Jim Rees, Neal Foster, and Edi Bletcher all correctly guessed that the item was an ink blotter.

Evidently Mr. Rees was correct when he commented, “This one was too easy.”

We’ll rectify that situation this week with this Mystery Artifact. Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

I think it’s an early telescope with a camera, one that can rotate to take long exposures.

Interesting guess Fritz. Of course photography was available at this time; one of the photographs of the rescue, taken by a photographer from the 1884 rescue ships, was of prostrated Cape Sabine survivors lying under a collapsed tent, too weak to erect it properly.

Its the theodolite… see [link]

I think that’s a theodolite, perhaps similar to the one Israel would have used on the voyage. I can’t tell from the image if it’s a transit or not, but I’ll guess not; it doesn’t look like you could flip that scope for backsighting.

It does make sense that it is a measuring device (theodolite, transit). And an ‘early’ telescope would date back to the 13th or 14th centuries and would have been far less complex than this (think pirate movie, sort of).

“Of course photography was available at this time”. Laura you seem to be implying that ‘at this time’ was somewhere in the middle to late 1800’s by the statements that follow about the rescue. The photography that was available at the time of the rescue was most probably one of a handful of wet plate processes that followed the daguerreotype; flexible film was invented by Eastman Kodak around 1885 but then took years to be produced and available. Wet plates were metal or glass plates that were treated, or had treated paper, that would react to light to capture the images. These plates were also large, compared to the film that followed, and do not appear to be compatible with the ‘mystery object’.

Trivia – the first photo of space taken with a telescope was in 1880; the birth of astrophotography.

Oh and for the record (if there is a record) I was not correct with my guess on the last ‘mystery object’; I learned from my neighbors. Thank you all.

George Lessard: Hmm, that does look vaguely similar. But of course a lot of measuring instruments also look vaguely similar…

cmadler: “it doesn’t look like you could flip that scope for backsighting”: good heavens, people, I feel like I’ve stumbled into a convention of surveyors here… :)

ABC: That’s neat about the beginning of astrophotography. Didn’t know that.

Photography: One photographer from one rescue boat took his box camera onto the shore of Cape Sabine to document the rescue. To give you an idea about conditions on the island, the large and heavy camera on a sturdy tripod kept getting blown over by the gale-like wind. He ended up only taking 2 pictures, 2 of the collapsed tent and two of the burial ridge, before giving up.

My mother is a relative of Edward Israel (yes, she is up there in age) and was researching the expedition on the internet when she happened on the article that you just wrote. She would love to speak to you about your research. She’s very slow on the computer so it would be easier for her to talk via phone. If you’d be willing to talk with her, please e-mail me.

Gail: I was thrilled to read your note here and have sent you an email.

It does look like a theodolite, and it does seem to have a spirit level, but where are the scales for measuring the angles? That tiny dial to the left of the scope doesn’t seem big enough.