Column: Book Fare

Where’s a medieval village when you need one?

You know – that place where everyone knows where everyone else lives and everybody knows everybody else’s business and, no matter how insipid or irrelevant, has an idiotic opinion on it all, one generally borne of grinding frustration, depthless boredom and a general, yawning poverty of the spirit …

No. I do not need to get on Facebook.

But maybe somebody out there who is plugged into this dynamic global engine of online communal solidarity-ishness can take a break from investigating what your fifth-grade gym teacher had for breakfast and help us out here.

The mystery opens a few days after Christmas, when my husband and brother-in-law drop me at the Borders in Peoria, Ill., on the way to relive their childhood at a matinee screening of “Tron: Legacy.” Browsing the history section, I come across a paperback edition of “Life in a Medieval Village,” by Frances and Joseph Gies, and settle into an armchair.

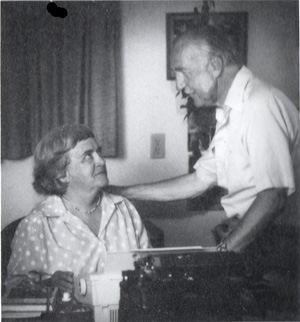

And there I learn, from the back cover, that the Gieses “live on a lake near Ann Arbor, Michigan.” And there’s this dear photo of an elderly pair who appear to be Grandma and Grandpa circa 1948, but they’re also two scholars who’ve spent their lives together researching and writing almost two dozen books about life in the Middle Ages. How cool is that?

Thus intrigued, this MA in history delves into meaty research the very day we get home after the holidays. And what do I learn from Wikipedia? That Mr. Gies, University of Michigan class of 1939, passed away on April 6, 2006, and, with Frances, “collaborated on a number of books” that “are respected amongst historians and archeologists.”

So the opportunity has passed to talk to this gentleman about the prodigious work of a lifetime. But all is not lost. So it is on to the Ann Arbor District Library to collect two armloads of the Gieses’ books in hardback, including “Life in a Medieval Village”:

The modern village is place where its inhabitants live, but not necessarily or even probably where they work. The medieval village, in contrast, was the primary community to which its people belonged for all life’s purposes. There they lived, there they labored, there they socialized, loved, married, brewed and drank ale, sinned, went to church, paid fines, had children in and out of wedlock, borrowed and lent money, tools, and grain, quarreled and fought, and got sick and died.

Tack on “paid dearly to eat sandwiches at Zingerman’s and waste many a fine fall afternoon at Michigan Stadium” and that pretty much sums up Ann Arbor in 2011, no?

Of course not. People come and go so quickly here – as did the Gieses, a progression of book flaps informs us. In 1974, when “Life in a Medieval Castle” was published, they lived in the Chicago suburb of Barrington. When “Women in the Middle Ages” came out in 1978, they had moved in Oakton, Va. The parents of three and grandparents of three more were living on that lake near Ann Arbor when HarperPerennial brought out the paperback edition of “Life in a Medieval Village” in 1991. “Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel” followed in 1994; “A Medieval Family” was published in 1998. Local obituary records show that Mr. Gies was in his 90s when he died in Maine in April 2006.

Then, as always when you’re sleepless at 3 a.m., inspiration seizes you: The go-to guy here has to be über-townie Geoff Larcom, formerly of The Ann Arbor News and now a media guy for Eastern Michigan University. My erstwhile colleague, who is on a first-name basis with every single person in the world born after the Spanish-American War who ever lived in Ann Arbor, can tell me all about the Gieses.

Or not. All Geoff can do is helpfully point out a typo in my e-mail and otherwise show off. As far as he knows,

The only Gies (not Giesn) were the late Tom and Thelma Gies. He was a prominent business prof for U-M. Died about 20 years ago, and Thelma recently. Lovely couple, but likely not related to Frances and Joseph. Tom and Thelma’s son, Chris, has a son named TJ that [sic] works for The Pistons.

When he finds out what TJ had for breakfast on Thursday, Geoff will no doubt fill me in. (In that same e-mail, Geoff told me he was wearing a “grey shirt with black-themed tie” – I did inquire – but here’s a word to the media relations folks at EMU: Don’t be fooled. In a newsroom bulging with competition, Geoffy was the sartorial eyesore. The mere memory of that taxi-yellow shirt with the red golf tie can still bring on the dry heaves.)

If Geoff can’t help, maybe the rest of the world can. So now I’m scattering this on the cyberwaters: Whither Frances Gies?

The Latest Fuss over Huck Finn

The instantly notorious “Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn: The NewSouth Edition” officially hits the bookstores on Tuesday. This is the version “edited” by Auburn University’s Alan Gribben to banish the word “nigger” and replace it with the word “slave.” Gribben says his intent is to secure the novel’s place on school reading lists. Much airtime and print space was given over to outrage. But how many of us merely rolled our eyes when we heard the news?

However well-intentioned, this latest attempt to “cope” with the racially offensive language that makes Twain’s great novel a routine target for censors on school boards is a silly one. But it will take its place in the continuing and decidedly un-silly debate over how to teach “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

Here’s my take: The “S” word describes an abomination that many Americans honestly view as a mere bygone. The history of slavery in the United States is quite a bit more. The “N” word is an abomination that many Americans would prefer be gone from the language. It won’t – and it shouldn’t be gone from Twain’s imperfect masterpiece. And to “cleanse” the novel of it is as dishonest and ultimately pointless as taking to the House floor to recite a Constitution cleansed of the Founders’ tally of one slave as three-fifths of a person.

But in a New York Times op-ed piece (“Send Huck Finn to College,” Jan. 16, 2011), short-story writer Lorrie Moore introduces something new to this old fight. Speaking from what she calls “a mother’s perspective,” Moore argues that “‘Huckleberry Finn’ is not an appropriate introduction to serious literature” and that it fails as a tool for encouraging young people – including “the young black American male of today” – to read great literature. So, Moore suggests, why not wait to teach it at the university level, “where the students have more experience with racial attitudes and literature”?

While she doesn’t fully address the controversy – if “Huckleberry Finn” isn’t part of the curriculum, it should still be on the shelves in whatever middle and high school libraries still exist these days – Moore makes important points.

I’m not speaking from a mother’s perspective or a teacher’s perspective. I’m speaking from the perspective of another reader who deeply admires this great novel – complete with its ending, which reduces drama to farce. “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” ends with boys’ play – Tom Sawyer appears on the scene and persuades Huck to make an “adventure” out of rescuing the again-captive Jim – perhaps because to end it with Huck and Jim triumphing on their own would have been farce in another form.

Huck Finn first appears in “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” – which, Twain wrote, “is not a boy’s book at all. … It is only written for adults.” With “Huckleberry Finn,” these two books about boys have been twinned and maybe shouldn’t be. I gave copies of both to my nephew for his ninth birthday last summer. While I hoped he’d be able to enjoy Tom now, I assumed Huck would sit on his shelf, hopefully for “later.” While “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” is a story for children and for adults, “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is not a “boy’s book.”

Local Poets Get National Play

Thomas Lynch of Milford, Mich. – a small town north of Ann Arbor – introduces Argyle the sin-eater in four poems that appear in the February issue of Poetry magazine. All that’s to admire about Lynch’s work is on display as he takes us to Ireland and explores to the pace of a beating heart his themes of death, faith, love and – here in “He Posits Certain Mysteries” – mercy, after a suicide:

… Argyle refused their shilling coin

and helped them build a box and dig a grave.

“Your boy’s no profligate or prodigal,”

he said, “only a wounded pilgrim like us all ….”

Lynch’s “The Sin-eater: A Breviary,” upcoming from Paraclete Press, has us looking forward to autumn. [Editor's note: Lynch's latest collection of poetry, "Walking Papers," was reviewed in the October 2010 Book Fare column.]

“Still Life,” a jewel by the University of Michigan’s Linda Gregerson, was set in an impressive two-page facing spread in the Nov. 29 issue of The New Yorker. And in December, Poetry featured “The Selvage” by Gregerson and a pair of poems by Charles Baxter, whose novel “The Feast of Love” secures him as a permanent local in my book, even if he did decamp for Minnesota. Baxter’s weavings of music and memory are shot with metallic threads of pain in both “Please Marry Me” and “Some Instances.” December was “The Q&A Issue,” and the brief discussions with the poets that follow each work are a real treat.

Local Readings

Deborah Rodriguez, author of the 2007 memoir and book club favorite “Kabul Beauty School,” reads from new novel “A Cup of Friendship” on Saturday, Jan. 29, at 3 p.m. at Nicola’s Books.

University of Michigan’s Nicholas Delbanco reads from “Lastingness: The Art of Old Age,” at the downtown Borders on East Liberty at 7 p.m. on Monday, Jan. 31, and at Nicola’s Books at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, Feb. 8. You might have heard Delbanco talking about late-life creativity on NPR’s “All Things Considered” on Jan. 21 (or read Brooke Allen’s tetchy take on the book and its writer in the Jan. 23 New York Times Book Review). While some artists run out of gas as they run out of years, Delbanco observes, others develop a sharper focus and a deeper intensity in the liberation found in work as its own purpose. Good news for the really, really late bloomers among us.

The UM English Department’s Zell Visiting Writers Series brings National Book Award finalists Mary Gaitskill and Carl Phillips to town next month. Gaitskill, a novelist and UM grad, reads on Thursday, Feb. 10; poet Phillips appears a week later, on Feb. 17. UM grads Suzanne Hancock, a poet, and fiction writer Valerie Laken (“Dream House”) will also read, on Thursday, Feb. 24. The Zell events start at 5:10 p.m. at the UM Museum of Art’s Helmut Stern Auditorium.

About the writer: Domenica Trevor lives in Ann Arbor and sort of enjoys being tetchy, from time to time. Her reviews for The Ann Arbor Chronicle appear on the last Saturday of each month.

No, Huckleberry Finn is not just a boy’s book. It is a book for the ages.

I read it when I was of middle-school age, living in a segregated town in Oklahoma just before the civil rights era came into full bloom. It helped usher me into fully-aware adulthood.

BTW, at that time the N-word was not used only as a pejorative, though it was understood to be not very polite. At Christmastime, I sold a candy at my local five and dime that farmers would come in and ask for by the name “N-toes”. I recall being just mildly scandalized at their lack of class.

This was very fun to read. I think I need to look for the Gies’ books to read; any mention of which lake they lived on near Ann Arbor?