Domenica Trevor

Start with some quick history: Josef Stalin’s campaign in the late 1930s to consolidate his control of the Communist Party spun into a terror that counted both old Bolsheviks and a new generation of party faithful among its victims. The leadership of the Red Army was decimated. Intellectuals were seized and interrogated and, like so many others under torture, falsely denounced others.

Inevitably, the masses caught on to the madness; pointing the finger at a neighbor could suddenly open up that three-room apartment next door. By the time the rampage was reined in, some 1.5 million people had been arrested and imprisoned; half again as many were executed or perished in the gulag.

Fast forward to the present: You’re a 29-year-old with an MFA, in Moscow to do research for your first novel. Lev Mendelevich Gurvich, himself caught up in the purges, has welcomed you into his apartment and has agreed to tell you his story. Gurvich, in his 90s but still with a sharp mind, had in the 1930s been editor of the literary magazine of the Komsomol, the Communist youth movement of the U.S.S.R. He was arrested, interrogated, sent to a labor camp.

You tell him about your novel, the story of a disgraced teacher of literature who now works as an “archivist” at Moscow’s infamous Lubyanka prison. Pavel Dubrov’s guilt and sorrow threaten to deaden him into numbness until a brief, official encounter with the prisoner Isaac Babel stirs him to rescue the condemned writer’s last manuscript from the prison’s furnace. Pavel smuggles it out of Lubyanka under his coat.

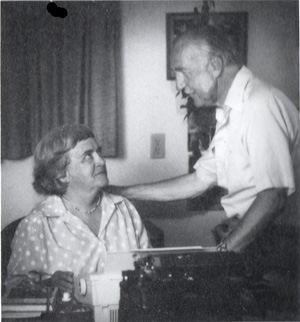

I met Babel, this survivor of the gulag tells you. I was at Stalin’s rallies; yes, I heard Stalin speak. But at one point the old man stops to ask, pointedly if not unkindly: Who are you to write this book?

“I wasn’t insulted,” Travis Holland says. “It was a question I asked myself.”

A more than fair question. But Holland’s answer, “The Archivist’s Story,” proved that his audacity was matched by his gifts. [Full Story]