In the Archives: Forgotten Phones

Editor’s note: Owners of new phones nowadays are as likely to think about the first photograph they’ll take with it as they are to contemplate the first words they’ll say into it. But Laura Bien’s local history column this week serves as a reminder that sometimes first words spoken into a phone get remembered in the historical archives. Given what she’s unearthed from the archives this time, it’s not clear why Chicago is known as the “city of broad shoulders” instead of the “city of big-footed girls.”

Quiz a friend or two about who popularized the type of electricity we use today – go ahead, get your geek on – and a few would correctly name Nikola Tesla. Then ask who invented long-distance telephony.

Probably no one would answer correctly.

It wasn’t Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, or any other celebrated name from the late 19th century’s feverish and fertile age of invention.

Like his renowned contemporary, Tesla, the inventor of long-distance telephony was an electrical engineer. Unlike Tesla’s numerous, sophisticated, and lasting inventions, his were few, crude, and transient.

But they worked – and brought him temporary fame.

Just as Tesla’s brilliance and legacy weren’t fully appreciated until long after his death, so too should be remembered the legacy of his humbler brother inventor whose name once graced the New York Times: Ypsilanti engineer Webster Gillett.

Born around 1840, Webster and his older brother Charles and younger sister Alma grew up on their parents’ 80-acre farm just east of Ypsilanti. Webster’s father Jason kept a few milk cows and pigs and a small flock of sheep. He raised wheat, Indian corn, and oats. Jason was a hard-working farmer. Between 1850 and 1870, his farm grew in size from 80 to 135 acres and its value rose from $1,000 to $10,000 [$170,000 today]. He was one of the more successful farmers in his neighborhood.

Around 1870, Jason’s 29-year-old son Webster also found success. He was granted the first of what would be nine patents – one for an electric alarm for use on railroad cars. Soon after, he obtained another – for an electrical temperature signal. The device received a mention in the Nov. 9, 1872 issue of The Telegrapher magazine, published in New York.

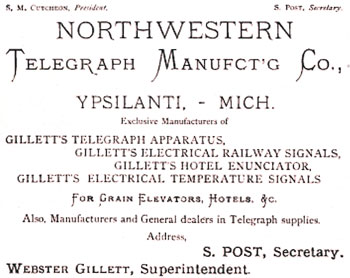

A year later, at age 33, Webster was superintendent of Ypsilanti’s Northwestern Telegraph Manufacturing Co. The company made and sold “Gillett’s Telegraph Apparatus, Gillett’s Electrical Railway Signals, Gillett’s Electrical Temperature Signals,” and “Gillett’s Hotel Enunciator.”

The hotel enunciator, also called “annunciator,” was similar to a hospital call-button system. Hotel guests could use it to summon room service. Webster was not the first to invent an annunciator, but his work on a device for communication over distance presaged his work to come.

Around 1880, at age 40, Webster began his most important and productive period of work. Between March of 1879 and the fall of 1880 he was granted three patents: for a method of adapting telegraph lines for telephone transmission; and for two versions of a speaking telephone (just a few years after Bell’s original telephone patent). Webster assigned one half of one telephone patent to Brooklyn engineer Richard Schermerhorn. He said farewell to his parents on the farm and moved to New York City.

Considering that the telephone is a direct outgrowth of the telegraph, it’s unsurprising that Webster got involved in a telephone equipment company in his new home of Brooklyn. He wasn’t alone in doing so. Telephony was the cutting-edge technology of the day and many inventors were contributing ideas. There was only one technological problem that even Alexander Graham Bell couldn’t solve: long-distance calls.

Telephony works by creating an electrical wave whose shape mirrors the sound wave of a speaker’s voice. At the receiving end, the electrical signal is converted back into a sound wave, producing recognizable speech. The only problem, in Webster’s day, was that the electrical signal was weak, and upon encountering resistance in the wire, soon petered out.

An obvious solution would be to provide a stronger electrical current from the transmitting end to push the signal farther. This wasn’t possible – too much current burned out the delicate needle-and-diaphragm apparatus that converted sound into an electrical wave.

Webster created a mechanical solution to this electrical problem. He simply added more needle-diaphragm pairs, each with its own battery power supply. First he invented a “two-point” (two needle-diaphragms) telephone. This instantly doubled the power pushing the signal down the line. He next created a four-point and a ten-point telephone. His crowning achievement was the twenty-point telephone.

This baroque device contained what resembled a candelabra of twenty needles and diaphragms. A voice speaking into the telephone made all twenty needles quiver. Each needle was wired to its own independent battery. The powerful combined signal surged much farther down the wires than ever before.

“Experiments were made last night on the large wire of the Postal Telegraph Company between New York and Meadville, Penn., a distance of 500 miles, with a telephone devised by Prof. Webster Gillett, of Ypsilanti, Mich.,” reported the Dec. 20, 1883 New York Times.

At the New York end of the wire were Prof. Gillett [and] Judge E. R. Wiggins, of Boston, the President of the Atlantic and Pacific Telephone Company, which owns the patents … Alfred Beal was at the Meadville end … there was little difficulty in carrying on a conversation. The gentlemen here held receivers to their ears, while Mr. Beal addressed them and sang ‘Way Down Upon the Swanee River’ and ‘Old Black Joe,’ which came plainly over the wire. Prof. Gillett asked Mr. Beal for a piece of his wedding cake. Judge Wiggins said he could hear Mr. Beal blush. The provocation for the blush was listening in Meadville.

The paper continued:

What Prof. Gillett calls a 10-point instrument was used. He uses in his transmitter a needle attached to a rubber disc … Each point, Prof. Gillett says, is like adding another telephone in power… “We feel confident that before we get through we are going to say ‘Hello’ and a good deal more, too, to the people on the other side,” said Prof. Gillett. “What we are aiming at is communication at long distances.”

Webster’s aim was true. Before long, his innovation enabled a call from New York to Chicago’s famed meat-packing titan, Philip Armour. The question that came over the wire to Mr. Armour, according to the Feb. 6, 1885 New York Times, was:

“Is it true that Chicago girls have big feet?”

“With painful deliberation,” reported the Times, “[the caller] spoke this query into a little transmitter of one of Webster Gillett’s long-distance telephones last night. The agitated diaphragm passed the interrogation on to one of the Postal Telegraph Company’s wires, and on the copper highway it sped on to Chicago …”

What the paper called the “eminent pork expert,” Philip Armour, “pondered long, and finally answered sorrowfully, ‘They have.’”

Advances in telephone equipment soon made Webster’s intricate phones obsolete. His name is absent from encyclopedias and telephone histories.

But for a moment in the 1880s, the Ypsilanti inventor, whose sheer brainpower whisked him from a humble farm to a cosmopolitan city and won him momentary fame, was at the forefront of long-distance technology.

Mystery Artifact

Your humble author is completely bumfoozled as to how such a crowd of prescient folks immediately and correctly pegged last column’s enigmatic Mystery Artifact as a toaster.

Matthew Naud, ‘FF’LO, Rod Johnson, Anna Ercoli Schnitzer, and Jim Rees all guessed correctly. My goodness. And here I thought I’d picked a stumper.

So we’re stepping up the challenge this time. This Mystery Artifact comes from an Ypsilanti artifact collector and friend who may have in his possession a greater number of artifacts than even exist within the Ypsilanti Museum. Among his gems is this four-inch-long puzzler. What on earth could it be? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and the upcoming book “Hidden Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

Was the “no small feet” subtitle a joke? Or maybe a secret reference to the mystery object? If so, I didn’t get it. Too large a feat for me.

Vivienne Armentrout: Much as I wish I could step up and claim that wonderful subtitle, I’d be a heel if I did so–my editor has sole credit.

I believe that object is used to help remove boots? So perhaps there is a hint in the article. I’ve seen them in antique stores, and in use. They are heavy, to help the boot be pried off hands free, so especially helpful when muddy.

I’m gonna go with ashtray. I mean, whatever it is, it could be used as an ashtray.

Linda: I think I know exactly what you mean; Ive seen them too. Sort of a big cast-iron cricket with big antennae: you put your boot within the antennae and use them to pull it off. Good guess! However, this item (also cast iron) is small; it would fit nicely in one’s hand. Hmmm….

‘FF’LO: You certainly could use it as an ashtray…but its owner said it has a much different function. :)

It looks like like it could keep some secret stash dry out in the garden.

Do I dare suggest, with Valentine’s Day just past, that the object is a dispenser for capsules of Spanish Fly?

Sebastian: Indeed, you’d never guess that this item has a secret compartment. It’s quite beautiful and detailed too, for what it served as: if you turn it over and look at the fly abdomen, it is beautifully and realistically striated.

Cosmonican: That guess made me smile…but I will say that in this case, unlike previous Mystery Artifacts, the form is divorced from its onetime function.

It’s a match safe. I have one similar to this, only mine is painted. It will hold about a dozen or so small wooden matches.

Barbara: Interesting guess…we shall see. :)

Ahh… the perfect cocktail s’more machine. You know long ago people realized that a s’more was too big for your mouth. That is when the mini marshmallow was invented, followed quickly in very elite circles by the ‘cocktail s’more’. This neat little device eliminates the need for a stick (how gauche!) as well as sticky fingers. Place this simple cast piece on a wood stove to get warm. Assemble your s’more in the fly’s abdomen and lower the lid. It works like a mini Panini maker. Watch the wings, their descent signals that all is melting according to plan. Lift the lid and there you have it; cocktail s’mores.

(Wags finger) Ah ah ah, ABC, have you been chatting with nationally-known culinary historian Jan Longone over at the Clements Library? Because…now, that wouldn’t be quite fair, would it? :)

No fair mounting the wire bread holders sideways on the toaster. That really threw me off.

Finally, a subject I know something about. By 1890, Gillett’s transmitter had been completely displaced by Thomas Edison’s carbon transmitter, which is even capable of amplification. The carbon transmitter was used for a hundred years before being replaced by dynamic and electret mics in electronic phones. The phones at my house are mostly Western Electric sets from the 1960s, and have carbon transmitters.

On a related subject, I was at Hathaway’s a couple weeks ago and was distressed to find that the telephones were missing. I hope they are just out for repair and not gone forever. Those phones are probably 100 years old, and are battery powered with hand crank ringer magnetos.

Jim Rees: Thank you for adding some very interesting info to the story. Gillett’s moment in the sun was short. I did not know that the carbon transmitter was in use for a century (!).

Your collection sounds neat. I also collect old phones, including a working model from the early 1940s which I love. Heavy thing. At one point I had about seven wired in sequence on top of the piano, so when a call came in, they rang ALL AT ONCE! You could hear them from quite a distance! Good times.

I think the mystery object is a whimsical honey pot.

Irene Hieber