Column: Book Fare

A chief function of the book review “industry” is to give new books a sales push – the “latest” is the point. But today, let’s hear it for the backlist – otherwise known as those books you took note of months (or years) ago and intended to read, or brought home, placed on the shelf and have noted with good intentions ever since.

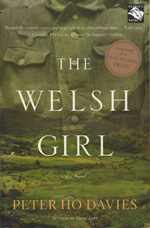

Two works of fiction by University of Michigan creative writing teacher Peter Ho Davies spent way too much time on my “gotta get to” list. And “The Welsh Girl” (2007) and “The Ugliest House in the World” (1997) were fine company when I finally claimed for them a couple of snowy weeks in February.

“The Ugliest House in the World” (Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin) is a collection of deftly composed short stories that are tragic, comic and often a dead-on blend of the two. They take us from colonial southern Africa to anti-colonial Kuala Lumpur, from Wales to – hilariously – Welsh-speaking Patagonia. (“Butch should have known it would come to this when the Kid started shooting ostriches again.”) And while we know things won’t end well for the British in Natal, the officers’ dining-table tales of heroism in the face of Zulu savagery are a ripping good time.

Davies’ tragicomic pitch is perfect in “The Silver Screen.” Meetings of the central committee of the Fourteenth Branch of the Kuala Lumpur Communist Party also serve as life-study sessions for Lee, an aspiring local artist who paints posters to advertise Hollywood films (the operator of the local movie theater is a comrade):

There was an unwritten law that during meetings Lee would be ignored, while the serious business of world communism was conducted. Yet on certain evenings – the night that Lee was sketching his poster of Henry Fonda in The Grapes of Wrath, for instance – the communists would argue longer and more passionately, with more sweeping strokes of the hand, their heads held higher and their brows creased deeper.

On the other hand, no one would look up from his food the night that Lee was trying to get a likeness of Sydney Greenstreet. They all held their bowls of rice that much closer to their lips and waved their chopsticks before their faces as they talked.

The branch is eventually ordered into the jungle to join the fight against British occupation, and Lee finds himself with the platoon, documenting the drama with his sketchbook and pencil.

There is little to relieve the poignant sorrow in some of the stories. In “Union,” striking Welsh quarrymen struggle to hold their families together and to hold out against the English mine owners who employ starvation and Cornishmen as strikebreakers. In the title story and “I Don’t Know, What Do You Think?” Davies is stealthy in sliding a revelation in here, slipping the tissue off another there, until he’s laid the full, sad state of affairs before you.

He exhibits an unsentimental compassion for human frailty, and there are recurring allusions to what ordinary people risk when they choose to claim simple pleasures. And his narratives are marked by quick bursts of horror – a new lamb is untangled from fence wire, but not before it has lost an eye to a patient crow; a machete-wielding rebel commander gives a fearful villager a swift lesson in the paramount importance of the present moment; a dragoon sergeant crushes a defiant Welshman’s fists with a rifle butt: “The sound of breaking bone could be heard all the way down High Street.”

The centrality and illusoriness of ethnic identity is the unifying theme of Davies’ work (little accident – he was born in Britain to a Welsh father and Chinese mother) and at the heart of “The Welsh Girl.” Outside a village in the hills of North Wales, unwelcome English soldiers have finished a camp that is to house German prisoners seized after D-Day. Many of the villagers are indifferent or feign to be – the English are the real enemy – but the foreigners behind the fence are irresistible to the boys in the village.

Jim, a child evacuee from the Blitz, at first calls them “nasties.” One prisoner in particular – Karsten, whose “smattering” of English gives him the power to choose whether his unit will surrender or burn – fascinates Esther, the Welsh girl of the title and the literal embodiment of cultural ambiguity. A parallel story – that of a German refugee whose language skills are of use in the British interrogation of the captive Rudolf Hess – adds another layer of profound complexity to Davies’ novel, which was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize.

“The Welsh Girl” is a remarkable meditation on nationalism as both the impetus to destructive power and a bunker for the powerless. When is a sense of place a curse instead of a comfort? What kind of powers do captives hold? What happens to innocents caught on the fence?

Davies, who is on the faculty of the MFA program in creative writing at UM, says he is at work on a novel and a new collection of stories, “but they’re a couple of years away as yet.” In the meantime, delve into Davies’ backlist. And after you finish “The Welsh Girl,” check out “Deleted Scenes” in the Odds, Ends & Outtakes section of Davies’ website. Yes, there’s more.

The Steads at Nicola’s Books

Ann Arbor’s Erin Stead, who won the 2010 Caldecott Award for her illustrations in “A Sick Day for Amos McGee,” will visit Nicola’s Books with her husband, Philip, the book’s author, at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, March 8. The store is located in the Westgate Shopping Center, at the corner of Jackson and Maple. And check out a very charming profile of the couple in February’s Ann Arbor Observer.

A book group that I belonged to in 2007 read The Welsh Girl and loved it. Oh, we didn’t all agree on its strengths and weaknesses, of course, nor on why it appealed to us, but we loved discussing it. “What is said in book group stays in book group,” so I can only share here what I wrote in my own book journal at the time:

“The stories of three main characters entwine beautifully: 1) a young man whose German father was Jewish, his mother Canadian, now in Britain trying to figure out his place in the world, 2) a German prisoner of war trying to overcome his shame at surrendering, 3) a 17-year-old Welsh barmaid trying to figure out how to help her father run their sheep farm without her mother, who died recently. The language is beautiful, too.”

Some day I would like to read the rest of Peter Ho Davies’ work. Thanks for including this thought-provoking review in the Chronicle.