Column: Lawsuit Aftermath – 6 Months Clean

At a Jan. 18, 2011 hearing, the 22nd Circuit Court judge Melinda Morris entertained two motions by the city of Ann Arbor in response to a lawsuit filed by The Ann Arbor Chronicle.

The lawsuit alleged that during a July 19, 2010 session held by the city council, the council had violated the Michigan Open Meetings Act – by voting to enter into a closed session to discuss written attorney-client privileged communication, but instead straying from that narrow purpose to reach a public policy decision about medical marijuana businesses.

It’s uncontroversial that the council did make a decision in an open session on Aug. 5, 2010 to develop an ordinance that would ensconce medical marijuana businesses in local zoning regulations, by first establishing a moratorium on establishing additional medical marijuana businesses. What The Chronicle essentially alleged was that the Aug. 5 decision to develop local legislation on medical marijuana businesses had already been determined at the July 19 closed session.

The first motion by the city of Ann Arbor was rejected by Judge Morris. The city had asked her to find that The Chronicle’s suit was frivolous, not managing even to state a claim, and further asked that sanctions and fines be imposed.

However, on the city’s second motion – which asked Morris to find that there was insufficient evidence of an OMA violation to warrant subjecting councilmembers and the city attorney to depositions, and that she should dismiss the claim – Morris ruled in favor of the city of Ann Arbor.

In reaching the conclusion that additional discovery of facts should not be allowed, Morris appeared to give significant weight to councilmember depositions affidavits, which they all signed, asserting that they had voted to go into the closed session on July 19, 2010 in part to discuss a May 28, 2010 legal advice memo written by the city attorney, Stephen Postema. All the affidavits further asserted that the council had not made any decision during the July 19 closed session. Morris also appeared to give significant weight to the idea that even if an OMA violation occurred on July 19, then it would have been “cured” by the council’s deliberations and decision made during their open session at the Aug. 5, 2010 meeting.

In this report, we will review some points of legal interpretation on which we disagree with Judge Morris, including the significance of a surprising omission in the affidavits signed by the city attorney and the mayor.

But we begin with the observation that since being served The Chronicle’s lawsuit six months ago – about a closed session conducted on the claimed basis of attorney-client privilege – the city council has not held a single closed session of that kind. That’s easily the longest closed-session-free span the council has achieved for attorney-client privileged-based sessions in more than two years.

That seems to reflect an implicit acknowledgment by the city attorney and the council that they’d been holding more of these kinds of closed sessions than were actually warranted. We gave serious consideration to filing an appeal in this case. The council’s apparent change in behavior has convinced us that our decision not to allocate additional financial resources to an appeal was the right one. Part of our goal was to rectify a specific pattern of inappropriate behavior on the council’s part, and we appear to have achieved that.

Compared to the possibility of establishing new case law on a specific point, we think a more general approach to reform of the Michigan Open Meetings Act and the Freedom of Information Act, through legislative efforts, is likely to yield stronger and longer-lasting improvements in these open government laws.

The Pattern of Closed Sessions

By way of review, the basic requirement of the Open Meetings Act (OMA) is that all deliberations and decisions of a public body are supposed to be held at meetings that are open and accessible to the public. But the OMA also allows a public body, for a limited set of very narrowly-defined purposes, to conduct a session out of view of the public. Some of the more frequently used purposes for justification of Ann Arbor city council closed sessions include the following, from the statute:

15.268 Closed sessions; permissible purposes.

…

(c) For strategy and negotiation sessions connected with the negotiation of a collective bargaining agreement if either negotiating party requests a closed hearing.

(d) To consider the purchase or lease of real property up to the time an option to purchase or lease that real property is obtained.

(e) To consult with its attorney regarding trial or settlement strategy in connection with specific pending litigation, but only if an open meeting would have a detrimental financial effect on the litigating or settlement position of the public body

…

(h) To consider material exempt from discussion or disclosure by state or federal statute.

In layman’s terms, these exceptions can be summarized as involving labor negotiations, land acquisition, pending litigation, or discussion of attorney-client privileged information.

The closed session that was the subject of The Chronicle’s lawsuit was one for which the city relied on the exception specified in 15.268(h). Specifically, in its response to the lawsuit, the city defended the closed session under 15.268(h) by claiming that it had been held to discuss documents that were subject to the attorney-client privilege.

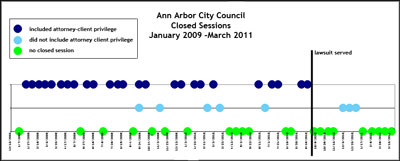

In reviewing the council minutes for more than two calendar years, we were able to identify an apparent change in the pattern of closed sessions held by the council since The Chronicle’s lawsuit was served on Sept. 24, 2010. Before that time, the council routinely held closed sessions based on discussion of attorney-client privileged material. Since our lawsuit was served, not one session of this type has been held. Further, it appears that the overall pattern of closed sessions based on other reasons has also decreased.

In the timeline representation below – of closed sessions held between January 2009 and March 2011 – bright green dots represent occasions when there was a city council meeting, but no closed session held. Light blue dots were closed sessions based only on some reason other than consideration of attorney-client privileged communication. Dark blue dots represent closed sessions that were based on reasons that included attorney-client privileged communication. The heavy vertical bar marks the date that The Chronicle lawsuit was served – Sept. 24, 2010.

Left to right is a timeline starting in January 2009, going through March 2011. Bright green dots represent occasions when there was a city council meeting, but no closed session held. Light blue dots were closed sessions based only on some reason other than attorney-client privileged communication. Dark blue dots represent closed sessions that were based on reasons that included attorney-client privileged communication. The heavy vertical bar marks the date when The Chronicle's lawsuit against the city was served. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Legal Issues

But just because the Ann Arbor city council appears to have stopped holding closed sessions with their city attorney based on attorney-client privileged communications is not an explicit admission they did anything wrong. It does, however, suggest that the city council and the city attorney are finally treating the attorney-client privileged closed sessions with the rigor they deserve.

The Chronicle never challenged the right of the city council, based on the OMA statute, to enter into a closed session to discuss attorney-client privileged information – it would be absurd to do so, because a public body clearly has that right. Yet city attorney Stephen Postema attempted to portray the controversy, in court briefs and to the media, as one about the right of the city council to hold a closed session. In refusing The Chronicle an interview after the hearing, Postema offered only the following written statement:

The Circuit Court properly dismissed this case and recognized that the Ann Arbor City Council did nothing improper in attending a closed session on July 19th, 2010. The Michigan Open Meetings Act specifically authorizes the City Council to attend such closed sessions to discuss attorney client communications.

By setting up a straw man about whether the council had a right to hold a closed session, Postema’s statement distracts from the actual controversy, which was this: Did the council use its July 19 closed session for its stated purpose, or did it instead stray from that purpose in a way that violated the OMA? Postema’s characterization notwithstanding, Judge Morris simply was not convinced that there was sufficient evidence to proceed with discovery, which would have included interviewing councilmembers and the city attorney under oath, and collecting documents that the city attorney may have shared with parties other than the city council, like the Michigan Association of Municipal Attorneys. Lack of discovery will leave history to wonder whether the council actually used that closed session in the manner allowed by the OMA statute.

What counts as the proper use of a closed session?

The OMA statute is clear about the limited set of reasons that can justify a closed session. Postema’s choice of the word “attend” to describe the council’s relationship to a closed session suggests that his concept of an appropriate use of a closed session is still flawed.

So in laying out why we still disagree with the conclusion reached by Judge Morris, we begin by asking: Whose closed session is it?

Legal Issues: Whose Closed Session Is It?

Postema’s description of the city council’s “attendance” at a closed session is somewhat odd, because it suggests that he and the council treat closed sessions as an event that someone other than the council itself convenes. That is, Postema’s phrasing suggests that council may decide to attend a closed session that exists apart from their own decision to vote to hold a closed session during one of their regular open meetings.

This concept of a closed session as an event that is conceived somehow external to the council – which someone else besides the council convenes and invites the council to attend – possibly stems from the practicalities of allowable closed session subject matter, as we’ve already listed out.

For example, an opportunity to sell or buy land might not be conveyed by a real estate professional directly to city council members. It’s reasonable to contemplate that the city administrator might receive an inquiry about real estate and then ask the council to convene a closed session so councilmembers can discuss it. The impetus to discuss pending litigation in a closed session logically originates with the city attorney, not the city council. Of course, by statute it’s the city council that must convene a closed session – by taking a roll call vote to do so.

So what about closed sessions based on discussion of attorney-client privileged communication – what should the impetus logically be for that kind of session? Based on prior court decisions, it’s clear that the impetus for an attorney-client privileged-based closed session should most naturally come from councilmembers, not from the city attorney. To see this, consider that:

- An attorney-client privileged-based closed session cannot be used just to hear oral advice from legal counsel. (Booth Newspapers v. Wyoming City Council)

- An attorney-client privileged-based closed session must be based on written material that is attorney-client privileged. (Booth Newspapers v. Wyoming City Council)

- The discussion in an attorney-client privileged-based closed session must be strictly related to the meaning of legal advice in the written communication. (State of Michigan v. Whitney)

Based strictly on the case law then, the only legitimate use by a public body of a closed session based on attorney-client privileged communication is for members of the body to discuss the meaning of legal advice in a written document.

As the affidavit of mayor John Hieftje makes clear, the impetus for holding a closed session on July 19 did not stem from a desire on the part of the mayor and other city councilmembers to discuss the meaning of legal advice in the May 28, 2010 memo, but rather was prompted by citizen complaints about medical marijuana businesses in their neighborhood:

4. On July 14, 2010 I received a complaint from a resident about medical marijuana dispensaries and forwarded it to staff at the City and Councilmembers Teall and Higgins. (attached)

5. On or about July 15, 2010, I requested that the City Attorney discuss with the City Council his prior legal advice memorandum dated May 28, 2010 concerning medical marijuana dispensaries and related legal issues in a closed session on July 19, 2010. (I had also initially requested the City Attorney prepare this legal advice memorandum at some point in the spring, 2010.)

Hieftje’s affidavit does not indicate that there was any lack of clarity on his or any city councilmember’s part about the meaning of the legal advice in the May 28 memo. The affidavits of councilmembers show that only two councilmembers spoke during the July 19 closed session – Sabra Briere (Ward 1) and Marcia Higgins (Ward 2) – and that they’d made comments in response to the city attorney, not asked questions. The rest of the time was taken up with the city attorney talking.

But a closed session is not a time for a city attorney to simply recapitulate orally what he’s already written. Assistant city attorney Abigail Elias acknowledged this in her remarks before the court on Jan. 18:

It is not a time for an attorney to read what he or she has written to the council.

And based on prior case law (Booth Newspapers v. Wyoming City Council ), a closed session is also not a time for the city attorney to render oral advice. Based on State of Michigan v. Whitney, a closed session is a time for councilmembers to discuss the meaning of the legal advice contained in a written communication. Indeed, as Elias put it during the Jan. 18 hearing [emphasis added]:

It is a time when there can be consideration and discussion of that written advice and as we all know, discussion requires some give and take, questions, answers. If there are none then there are none.

But if there were no questions from councilmembers, it’s not clear why the city attorney was talking at all. On entering the closed session, if it was apparent that councilmembers had no questions or uncertainties about the meaning of the legal advice contained in the May 28 memo, then the closed session should have ended – it should not have lasted even seven minutes. The council conducted a closed session on May 4, 2009 that lasted only two minutes.

Legal Issues: Was a Decision Made?

Instead of ending, the closed session continued, with the city attorney apparently using the opportunity to ask for and receive direction from the council to proceed down a path that would include developing local legislation regulating medical marijuana businesses. We base that assertion on the statement of Stephen Rapundalo (Ward 2) made at the Aug. 5, 2010 council meeting:

In fact, this was discussed at our last meeting and a directive was given to the city attorney at that time to bring this forward to this meeting tonight and I believe everybody was in the room when that was indicated.

Later, at the Sept. 7, 2010 council meeting, Rapundalo claimed that his original statement was a misrepresentation. But at the time of his statement on Aug. 5, no councilmember objected to Rapundalo’s characterization – nor did city attorney Postema. Only when threatened with a lawsuit did Rapundalo’s story change, leaving several questions unanswered.

At the Jan. 18 hearing, Elias tried to brush off Rapundalo’s original statement as simple misspeaking in the spontaneity of the moment:

They often have to be much more spontaneous at a council table. So we cannot hold them to every, single minutia of every statement, and if they want to correct a statement, that’s fine. It does not make them a liar. It does not make them untrustworthy. It does not make them an exaggerator or a falsifier.

We have no way of knowing if Judge Morris reviewed the video record we provided for her consideration. But if she did, we don’t think she could have found Elias’ suggestion plausible that Rapundalo appeared to be only guilty of spontaneous misspeaking.

Rapundalo made his remarks not in the context of a spontaneous back-and-forth interaction, but rather in the carefully controlled environment of the council’s parliamentary procedure. Remarks from Carsten Hohnke (Ward 5) and Margie Teall (Ward 4), to which Rapundalo was clearly responding, had come several minutes prior to the mayor’s giving Rapundalo the floor to speak. So there was adequate time for Rapundalo to weigh his remarks well in advance. He had additional time to reconsider the accuracy of what he said between the time he made his remarks and when the council later recessed, during which time he told The Chronicle he’d been talking about the July 19 closed session.

Postema told our legal counsel before we filed the lawsuit that we would have no way of proving that Postema or anyone on the council had even heard what Rapundalo had said on Aug. 5, 2010, or had understood what Rapundalo had meant, even if they’d heard it.

But in fact, the Community Television Network (CTN) local cable footage of that meeting shows Rapundalo’s Ward 2 colleague Tony Derezinski, seated to Rapundalo’s right, clearly nodding along to Rapundalo’s remarks.

Derezinski attended the Jan. 18 hearing. After the judge had ruled, The Chronicle asked Derezinski why he’d nodded in agreement with Rapundalo at the Aug. 5 meeting, if Rapundalo himself had later claimed his own remarks had been a misrepresentation. Derezinski replied, while still standing in the courtroom: “I wasn’t nodding.” Here’s the footage:

Further, after the Jan. 18 hearing, a council source told us that their recollection was that Postema had, in fact, used the July 19 closed session to ask for direction from the council; that he received that direction from Marcia Higgins (Ward 4), who told him she wanted a proposal for an ordinance drafted; and that she said wanted it to come before the council at the earliest possible occasion – the next meeting.

So, more plausible than councilmembers’ conclusory statements that there was no decision made at the closed session is our theory that a decision was made to proceed with a legislative strategy of developing local legislation to regulate, not ban, medical marijuana businesses.

We imagine it was similar to the interaction Postema and Derezinski had during the open session of the council’s Oct. 18, 2010 meeting, when Postema asked for direction on developing a licensing scheme for medical marijuana businesses, and Derezinski gave it to him. The step of getting direction is not a formality – it’s a requirement of the council’s rules, which state [emphasis added]:

RULE 13 – Ordinances, How Introduced

Proposed ordinances shall be introduced by one or more individual members of Council. Ordinances may be referred to any or all of the following: the City Attorney, the City Administrator, appropriate agencies, and Council committees, for study and recommendation.

The council’s apparent consensus, which we believe was reached at the July 19 closed session, thus effectuated the public policy that the city would enact some kind of ordinance to ensconce medical marijuana businesses in a local regulatory framework. In reviewing our arguments made to the court, we think we could have done a better job of identifying this as the public policy that the council effectuated during the July 19 closed session. An alternative policy the council could have effectuated would have been to acknowledge the supremacy of federal law in matters related to marijuana, as some communities in Michigan have done.

We think that decision, made out of public view, was a violation of the OMA.

At the Aug. 5, 2010 open session, the council then took a vote to carry that already-established public policy forward – using the mechanism of a moratorium on establishing additional medical marijuana businesses and a directive to the planning commission to develop zoning regulations for such businesses.

Elias argued before Judge Morris that even if there was an OMA violation at the July 19 closed session, the open discussions at the Aug. 5 meeting would have cured that violation:

… that was fully cured by the full open discussion of every possible aspect of the moratorium at the following council meeting.

The Chronicle’s legal counsel argued that subsequent action could not be curative, unless it were acknowledged to be a reenactment of a prior decision, in the context of the lawsuit. The actual paragraph from the OMA statute reads:

15.270 Sec. 10.(5) In any case where an action has been initiated to invalidate a decision of a public body on the ground that it was not taken in conformity with the requirements of this act, the public body may, without being deemed to make any admission contrary to its interest, reenact the disputed decision in conformity with this act. A decision reenacted in this manner shall be effective from the date of reenactment and shall not be declared invalid by reason of a deficiency in the procedure used for its initial enactment.

On the city of Ann Arbor’s interpretation of 15.270 Sec. 10.(5), a public body could routinely enter into a closed session at the start of each meeting, deliberate and vote on each item in a kind of dress rehearsal, then emerge from the closed session and conduct an open session in which all of the closed session violations would be cured, without mentioning that there was any connection at all to the activity in the closed session. That, we think, would an absurd interpretation of the statute.

Judge Morris seemed to be unaware of the existence of 15.270 Sec. 10.(5) when she asked Elias: “Under the statute a violation can be cured by such a subsequent event?” So to the extent that Morris even weighed the possible curative powers of the council’s Aug. 5, 2010 open session decision, she obviously disagreed with our interpretation of the statute.

Legal Issues: Purpose for Closed Session

Morris also apparently disagreed with our position that a closed session must be limited to the purpose that is declared when a public body votes to go into the closed session – even if the way that the closed session activity strays from its purpose might not constitute an OMA violation on its own. For example, all 11 councilmembers might decide they want to plan a birthday party together – they could meet out of view of the public to do that without posting any notice or announcement, or keeping any minutes.

But it’s our contention that planning a birthday party could not legally take place in a closed session of the city council – even though birthday party planning itself, when undertaken by a quorum of the council, would not constitute a violation of the OMA. Birthday party planning is simply not within the set of narrowly prescribed activities that are allowable during a closed session. So if a city council wants to plan a birthday party at one of its meetings, then it must do so during the open session of a meeting.

Morris clearly disagreed with us on that point, by saying she felt agenda setting, for example, would be allowable in a closed session without violating the OMA, even though agenda setting is not delineated in the statute among the set of allowable activities in a closed session. Morris stated at the Jan 18 hearing:

But if it was a resolution or bringing it forward sounds to me like putting it on the agenda. In this Court’s opinion … that by itself is not a violation of the Open Meetings Act …

Legal Issues: Statement of Purpose a Closed Session

If there’s been some improvement in the city council’s conduct regarding closed sessions, then it could be due to the fact that city attorney Stephen Postema might finally be starting to take seriously the idea that the council should at least have a clear understanding of what the purpose of a closed session is planned to be, before voting to go into closed session.

But based on an exchange between mayor John Hieftje and the city attorney at the council’s Dec. 4, 2010 meeting, Hieftje at that point didn’t quite seem to grasp the statutory requirement of stating exactly what the purpose of the closed session will be. A transcription from that meeting:

Hieftje: Are there communications from the city attorney?

Postema: No, mayor.

Hieftje: Other than that we have a closed session.

Postema: Yes, we do.

Hieftje: I was afraid of that.

[clerk's report accepted; opportunity for public commentary offered]

Hieftje: Seeing no one, would someone please move to go to closed session under the Michigan Open Meetings Act including, but not limited to labor neg…

Postema: … Nuh wait, this is on uhhh, pending litigation only, which is the middle one.

Hieftje: Limited to pending litigation. And attorney-client privileged communication.

Postema: No, it’s only under pending litigation, which is under the Open Meetings Act uh 15.268(e).

Hieftje: I was just trying to cover them all there.

Postema: Alright.

For Hieftje, the stated reason to go into a closed session can apparently include whatever grab-bag of reasons is allowable under the statute – without attention to what the actual purpose of the closed session is planned to be. If you “cover them all,” there’s less clarity for everyone about what the actual purpose of the closed session is, and that set of circumstances is more likely to result in violations of the OMA like the one that we believe occurred on July 19.

Legal Issues: Requirement of Written Communication

If the stated purpose of a closed session is to discuss attorney-client privileged communication, then based on Booth Newspapers v. Wyoming City Council, together with State of Michigan v. Whitney, the closed session discussion must pertain only to the meaning of specific legal advice contained in written communication.

So any councilmember voting to enter such a closed session could and should reasonably wonder: What written document will form the basis of our discussion, and do I have a copy of that document that I can refer to during that discussion? Of course, the statute does not explicitly require that members of a public body must be staring intently at a copy of the written communication during the closed session.

But based on the councilmember affidavits, plus statements made to The Chronicle by more than one councilmember, no one at the July 19 closed session had any written documents that were visually accessible to them. Indeed, it’s reportedly never the case that anyone ever has any written material in front of them for Ann Arbor city council closed sessions. Postema’s affidavit claims: “As is my practice, I had in my possession the attorney-client communications provided to the City Council …”

Having communications in your possession is a fairly capacious concept, ranging from (1) having a smart phone in your pocket through which you could download the documents, to (2) clutching a sheaf of papers and referring to them visually while you are speaking.

The fact that Postema had an opportunity to describe specifically how he visually appealed to the communications he was purportedly discussing with the council, but did not offer such a description, we conclude that perhaps he simply had the documents in his briefcase. It strikes us as absurd to think that a group of people could claim to be discussing a complex legal document without anyone in the room having an easily viewable copy of the document.

Of course, neither the statute itself, nor subsequent court cases, demand that a physical copy of the document be present in a closed session based on discussion of attorney-client privileged communication. Elias put it this way, in arguing before Judge Morris at the Jan. 18 hearing:

… there is nothing in any of the cases that says every member of the council must be clutching that written communication in their hands throughout the closed session … I don’t know what law he thinks he’s relying on that says they have to have written communication in front of them while it’s being discussed. It frankly isn’t there, and that is not a requirement of the Open Meetings Act.

While it’s not an explicitly stated requirement to have the document under discussion visible, it’s certainly hard to see how the spirit of the statute is served by members of a public body who use the existence of a written document – somewhere or anywhere in time and place – as a justification to have a closed session conversation based on that document.

We see this situation as analogous to public notice posting requirements of special meetings, as specified in the OMA. The statute only requires that a public notice exist somewhere at a public body’s principal offices. But the Attorney General’s Opinion 5724 introduces a notion of “accessibility” that requires the posting be accessible for the entire 18-hour posting period. It’s not enough for the posting to exist somewhere in the building – especially if the building could be locked. That would not serve the spirit and purpose of the statute.

Extending the reasoning in Opinion 5724 only slightly, we think it does not serve the spirit and purpose of the statute for a public body to be able to hold a discussion in a closed session about the meaning of legal advice contained in written communication, without that communication being accessible to members of the body. So while there’s no “clutching requirement,” any reasonable interpretation of the law and subsequent court cases would suggest there is an accessibility requirement – which the Ann Arbor city council did not meet on July 19. Obviously, Judge Morris did not agree with us on this point.

Legal Issues: Completeness of Affidavits

Because Judge Morris did not grant us reasonable discovery in this case, we did not learn until a few weeks after the hearing that the affidavits submitted by the city did not tell us or Judge Morris the complete story of the May 28 memo.

It had struck us as odd that in the course of communications between our counsel and the city attorney’s office, the May 28 memo was not ever mentioned as the basis of discussion for the July 19 closed session. The time lag between May 28 and July 19 also struck us as odd. And by late January, after the hearing, we’d pieced together substantial evidence that the July 19 closed session was not the first occasion on which the city council used a closed session to discuss the May 28 memo. Confronted with a specific question from our legal counsel on that issue, assistant city attorney Abigail Elias admitted:

… the May 28, 2010, privileged memorandum that was identified in the course of the recent litigation, was discussed at the second of two closed sessions on June 7, 2010;

The narratives in affidavits by mayor John Hieftje and city attorney Stephen Postema mention a specific request made by Hieftje to Postema a few days before July 19 to discuss the May 28 memo at a closed session on July 19. But neither of them mention the fact that the council had already discussed the May 28 memo at the June 7 closed session – for 13 minutes.

Certainly the existence of that previous closed session was relevant for the court’s understanding and evaluation of the issues and claims involved in our lawsuit. For example, Elias could not have made the same argument she made to Judge Morris against allowing depositions to proceed, if Hieftje and Postema had provided affidavits that included the relevant fact of the June 7 closed session. Responding to our legal counsel’s argument that the requested depositions would be short – only 45 minutes – Elias stated:

… he claims that they’re in theory short because they’re only 45 minutes. In this case where the only issue is what happened during the course of seven minutes, forty-five minutes seems to be nine times too long for each of those depositions.

Certainly Elias and Postema might try to argue that the only issue before the court was what happened on July 19, not any other closed session, and that’s why they were not required – by the ethics of their profession and Postema’s sworn statement that his affidavit was complete – to disclose the fact of the June 7 closed session about medical marijuana policy, based also on the May 28 memo, just as the July 19 closed session was purported to be.

For us, however, that argument would not survive a basic straight-face test. We think Judge Morris allowed her court to be misled by Postema and Elias.

Legislative Remedies

One possible path forward would have been to appeal Judge Morris’ ruling in the hope that we could establish as a matter of legal precedent that the way the Ann Arbor city council conducted its July 19 closed session violated the OMA. We ultimately decided that the narrow range of improvements in the behavior of public officials that are achievable with such a strategy would be fairly limited.

Based on a conversation we’ve had with Jeff Irwin – who was elected in November 2010 as state representative for District 53, which covers most of Ann Arbor – we think our best shot to achieve meaningful and lasting reform is to change the way the law is written with updated legislation.

That is, instead of trying to change the law by setting legal precedents in court, we will place our faith in the possibility of legislative change. One could imagine an OMA statute, for example, that simply did not include the attorney-client privileged communication exemption at all.

Irwin has already taken a first step. In his first month in office he sent a bill request to the Legislative Services Bureau (LSB) for legislation that would update the Freedom of Information Act. Each representative is allowed to make 10 bill requests in the first month of a term and five each month after that. So reform of open government laws is high on Irwin’s list of priorities.

Irwin reported that the LSB had advised that what he had in mind would likely need two bill requests – one for the Freedom of Information Act and one for the Open Meetings Act. He indicated that the legislature’s agenda will first handle the budget as a top priority – that’s fitting and proper – but reform in open government laws will get their due later in the year.

We’re counting on Irwin to generate some good news about open government in Michigan, so that we can report about progress in this area. We’ll sure be watching for it.

Thanks for pushing for more openness and transparency in city government. Government is as good as what we accept! If no one protests than nothing will change.

~Stew

This affair shows how a lawsuit can stop a dubious governmental practice even if it is ultimately dismissed.

At least the Chronicle didn’t get a SLAP suit.

I’m heartened that Irwin may take a look at the FOIA and OMA, but given the make-up of the legislature, opening this can of worms might actually produce a result that is contrary to your aims.

Congratulations to the success you apparently made in changing behavior, as shown by the chart. That is impressive.

What exactly were you looking for? If you would have won, what woudl you have asked for?