In the Archives: Women’s Underwear

Editor’s note: The Chronicle winds up March, which is Women’s History Month, with a column from publisher Mary Morgan about Jean Ledwith King, and Laura Bien’s regular local history column, which takes a look at women’s underwear.

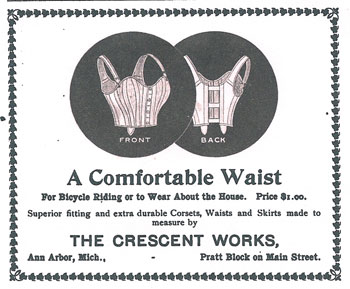

In 1894, Ann Arbor's Crescent Clasp Works at 39-41 North Main employed 13 women making corsets, waists, and hosiery. They included machine operators Clara and Lillie Scheffold, Minnie and Anna Schneider, Emma Tenfel, Kate Saunders, Eugenia Gauss, Ida Kuebler, Lilly Biermann, Ida Oesterlin, Dora Walz, Jennie Jacobus, and Anna Kuster, plus stenographers Clara Markham and Mary Pollock.

This time last year, census canvassers were going door-to-door, asking their 10 questions about each home’s residents, their individual sex, race, and age, and whether the property was mortgaged.

Imagine if they’d asked each woman about her style of underwear.

Thirteen thousand women were asked that question in 1892 by Michigan state officials.

The officials were male, but oddly enough it was women who were responsible for inserting the undergarment question into the state-funded survey.

The winding road to this naughty quiz began with an 1880s state governor who was concerned about the working class.

In his 1883 inaugural address, Michigan governor Josiah Begole proposed the creation of a state bureau to collect information about labor conditions. “Paupers and criminals,” he said, “the fish that swim in our rivers and lakes, and the cattle that graze in our fields, are cared for by commissioners appointed by the State. A large class of our citizens … have no one whose especial duty it is to investigate their condition … I refer to the laboring class.”

He had reason for concern. The following year’s report by the new Bureau of Labor and Industrial Statistics summarized data from 14 major manufacturing cities. It was found that the average workday was 10 hours long. Sawmill, salt mill, and shingle mill employees worked 11 to 15 hours per day, and streetcar drivers up to 17.

Worker accommodations at many job sites were deplorable. The 1884 report mentioned “the appalling poverty and squalidity of the poor [Wayne county] brickyard laborers. The destitution and wretchedness of life is rendered much more apparent … by reason of the filthy, dilapidated, little hovels into which the laborer is crowded. These usually consist of one room and a shed, and are built of ten-foot boards, standing on end, with the floor raised about two feet, making a room about eight feet high, by about ten feet square.” The average family, said the report, consisted of six people living in those 100 square feet.

The not unsympathetic report continued, “Unorganized, untaught, uncared for, seemingly unambitious, [immigrant] strangers in a strange land, with every waking hour devoted to satisfying the needs and desires of the physical man, these people seem scarcely to realize their humanity.”

The 1884 report took a cursory look at women in the workplace. It noted the daily wages of 502 women across the state. The average was 74 cents [$18 today], compared to $1.77 for men [$42 today]. The three women’s professions whose wage range offered a chance to earn up to $2 per day included clerks, dressmakers, and laundresses. The report also examined the wages of 500 domestics, or house servants. Most domestics earned between $2 and $3.50 per day (their pay included a stipend for personal expenses), but, if living at their employer’s home, were on call around the clock.

Despite low wages and a limited variety of “appropriate” jobs on the distaff side, women entered the workforce in ever greater numbers. In 1892, the state’s nine-year-old Bureau of Labor decided to focus on this growing trend, and devoted most of the yearly report to an analysis of women’s work.

Among the Bureau agents’ survey questions were two that had been included at the request of progressive women’s societies concerned about working women’s welfare.

In the working world, the well-meaning questions proved offensive. “A great many of whom the questions were asked thought no one had any right to receive any answer to them, not comprehending the statistical purposes in view,” groused the report’s writer.

One question asked which church the women attended (with the assumption that they were Christian) and whether they belonged to a ladies’ or community society. It seems probable that the forward-thinking women who’d campaigned to include this question viewed church and society membership as marks of a wholesome spiritual and moral condition. Of the 13,436 women surveyed, however, 10,729 didn’t respond.

The other question – pity the poor male Bureau official asking this of hundreds of female strangers – asked whether the lady wore a corset.

The report noted, “This question was requested to be asked of the women wage-workers by ladies interested in the welfare of their sex with a desire of ascertaining, if possible, the effect of the wearing of corsets upon women workers, and also to get an expression from the women themselves as to their effect upon health.”

The text continued, “An interesting feature of this report [is that] comparing the health of those who report not wearing corsets with the health of those [that] do, the percentage of good health we find largely in favor of those who report no.”

Taken in the context of the era’s Dress Reform Movement, which sought healthier, less restrictive clothing norms for women, and of a growing women’s rights movement in general, the question is less intrusive than radical. Progressive women sought greater freedom for their sex, and a safe place to begin reform was where it couldn’t be seen and jeered – namely, among the 19th century’s complicated and restrictive undergarments, hidden under outerwear.

Many working-class women agreed with dress reform. “I know from extensive observation that the wearing of corsets is very injurious to the health of women,” said one woman worker quoted in the Bureau’s survey. She continued, “[I] have been deeply interested in the ideas as promulgated by the Chautauqua dress reform ladies which this year [have] attracted more popular attention than ever before … the principal motive [of the movement is] to give greater freedom of motion to women, to dispense with the health-breaking corset, and to shift the weight of clothing from the waist … to the shoulders, where it ought to be. It is a serious matter, this dress reform idea … ”

“I advise no one to wear them. I think them injurious to working people,” said another working woman survey respondent. “In winter,” said another. “Sometimes when not working,” said one.

Echoing the sentiments of many, however, one woman snapped, “It is a personal affair.”

Of the 13,000 women surveyed, around 3,400 said they wore corsets; 232 said they didn’t. Nearly 10,000 did not respond. (No figures on the number who slapped the questioner’s face.)

After completing and turning in the report, Bureau officials likely felt relief to be free of the troublesome, embarrassing work and the indignant women.

But one final feminine sally blasted forth from the December 1892 issue of the Journal of the American Statistical Association. Statistician Laura Salmon had pored over the Bureau’s report.

“It is a matter of no small moment,” she began approvingly, “to stimulate among working women themselves a discussion concerning the sanitary conditions under which they work, the unhygienic features of women’s dress, the possibility of saving wages … ”

Salmon, however, took a dim view of the published report. After criticizing the Bureau’s ramshackle methodology, she excoriated its mangling of English.

Valuable information, she said, should be presented in a readable form for the public. “[I]nasmuch as the general public has yet to be educated to consider statistical reports interesting and valuable reading,” she said, “the presentation of statistical material in … [an] interesting manner is scarcely second in importance to [facts].”

“The majority of readers whose interest in statistics has yet to be won,” she said – perhaps with exasperation at the statistics-oblivious public – “are repelled by … ‘data’ used uniformly as a singular noun, the not infrequent use of a plural subject with a singular verb and the reverse, [the antique term] ‘widow lady,’ … and a score of inaccurate expressions too long to quote.”

“But far worse than this slovenly use of English – bad as it is,” she continued, building up a good head of steam, “is its undignified use. ‘Grass widow,’ ‘gents,’ ‘a hustling city,’ savor of the street corner rather than suggest the highest industrial authority in a great commonwealth.”

In closing, Laura blew the whistle. “Accuracy of mathematical work and grasp of statistical principles ought not to be incompatible with the presentation of a subject, if not in elegant, at least not in slovenly English.”

The gavel had fallen.

From that day to this, the State of Michigan has never again dared to question women about their undies.

Mystery Artifact

Last column’s Mystery Artifact seemed to suggest gruesome possibilities to more than one commenter … not without reason.

The 1924 medical device is an amputation retractor for pulling back a severed section of, say, leg flesh so as to obtain access to the bone. This device’s use is illustrated in its stomach-roiling patent drawing.

This column we venture from the professions to the trades with this odd item from the Ypsilanti Historical Museum’s tool room. What might it be? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and the upcoming “Hidden Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

Laura,

This article goes quite nicely with the one you did awhile back on riding bicycles in bloomers. The mystery item appears to be an early wooden and iron clamp. The threaded wood dowel could be turned to adjust for the thickness of the item being clamped.

After closer examination, the mystery item appears to be made entirely from wood. The shading on the clamps appeared to be iron, but I can see they are not.

That is an interesting observation Dave; as you know, bloomers were arguably the first dress reform garment, when Libby Miller/Cady Stanton/Amelia B. premiered them around 1850.

Interesting guess on the item. A relatively big artifact.

Re: [1] That’s not the same Dave as me who makes this observation: “This article goes quite nicely with the one you did awhile back on riding bicycles in bloomers. ” But I wish I’d made the connection myself in the editor’s note that starts off the piece. Here’s a link to the bicycles and bloomers column: [link]

“state governor who was concerned about the working class.”

How refreshing. Can we resurrect this guy and elect him?

No one’s guessing, so I suppose I’ll take a stab at it…

Looks like a harness vice that got detached from a saddle-makers bench. If it’s not for that exact purpose, it’s certainly made to hold leather while it’s being punched and stitched; you can even see the grooves where the awl rubbed the wood.

Dave A.: Thank you for excavating that bike-bloomers link: gosh, that seems like a long time ago! And strangely enough I’d write that story differently today. The stories do complement each other though, as the first Dave noted.

TeacherPatti: He did see genuinely concerned from what I read. But as noted, conditions in some places were pretty horrifying by modern standards. I can’t imagine trying to get through a winter in a 10 by 10 wooden box, no insulation, door directly to the frigid outdoors. Pretty grim.

Incidentally, though I didn’t look too deeply into it, it appears on the surface that Josiah Begole was not closely related to the onetime well-known local Begole/BeGole families in Ypsi and Dixboro.

Cosmonican: Now, that is an interesting guess. This item from the tool room is in very good condition; no broken/replaced parts &c.

The featured ad for the Corset Works is from 1896 or later since the Pratt Block, located at 306 S. Main (and just getting its cornice restored)was built in that year.It currently houses the WSG Gallery, Le Dog and other shops. The building was formerly part of the Kline’s complex and had its 1950s facade removed about 10 years ago.

Susan: Sorry, didn’t see your comment till now. The ad is from 1899; 1894 refers to Bureau of Labor and Industrial statistics I had for the workers at the company for that year. I should have clarified that; thank you for pointing it out.