Residents Frustrated by Dioxane Decision

About 50 residents gathered at Ann Arbor’s Abbot Elementary School late last month to get an update – and raise concerns – over a new consent judgment that changes the cleanup requirements of 1,4 dioxane contamination caused by the former Gelman Sciences manufacturing plant in Scio Township.

Matt Naud, the city of Ann Arbor's environmental coordinator, points to his home on a 3D map of the Pall-Gelman 1,4 dioxane plume. The map was constructed by Roger Rayle, a leader of Scio Residents for Safe Water, who brought it to the March 30 public meeting about a new consent judgment related to the plume. (Photos by the writer.)

Mitch Adelman, a supervisor with the Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality’s remediation division, began the March 30 meeting by acknowledging the crowd’s reaction to the new agreement, which was issued earlier in the month without opportunity for public input. “I don’t expect anything I say or do tonight to alleviate your anger or frustration,” he said.

But Adelman noted that if a company like Pall – which owns the former Gelman Sciences site – proposes a remediation plan that complies with state law, “we’re obligated to accept it.”

For nearly three hours, Adelman and Sybil Kolon, MDEQ’s project manager for the Pall site, gave an update and answered questions about the new consent judgment, the history of the cleanup, and what residents might expect in the coming years. They were challenged throughout the evening by people who’ve been following this situation closely – most notably by Roger Rayle, a leader of Scio Residents for Safe Water and member of the county’s Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD). Rayle has been tracking the dioxane plume for many years, and presented his own graphical renderings of data to the group.

The meeting was attended by several elected officials: Ann Arbor city councilmembers Stephen Rapundalo (Ward 2) and Mike Anglin (Ward 5); Ann Arbor Township supervisor Mike Moran; county commissioner Yousef Rabhi (District 11); and Sarah Curmi, chief of staff for state Sen. Rebekah Warren, whose district covers a large portion of Washtenaw County, including Ann Arbor and Scio Township, where the plume is concentrated.

1,4 Dioxane Plume: 40+ Years

In the 1960s, Gelman Sciences – a firm founded by Charles Gelman that manufactured medical filters and other microfiltration products – began pumping industrial wastewater into holding lagoons behind its factory at 600 Wagner Road in Scio Township. Some of those wastewater releases were permitted by the state. Contaminated groundwater leeched into underground aquifers, and by 1985, tests showed some local residential wells were contaminated with 1,4-dioxane, a substance that’s considered a carcinogen.

In 1988, the state filed a lawsuit against the company to force a cleanup. A consent judgment in the case was issued in 1992 by the Washtenaw County Circuit Court, setting out terms for handling the cleanup. The consent judgment has previously been amended twice – in 1996 and 1999. In addition, the court has issued several other cleanup-related orders, including a 2005 order prohibiting groundwater use in certain areas affected by the dioxane plume. The city of Ann Arbor filed a separate lawsuit in 2004, which was settled.

Building 1 at the Pall Corp. facility in Scio Township. No manufacturing is done now at the former Gelman Sciences plant, but a water treatment facility is located on the site to remediate 1,4 dioxane groundwater contamination.

Meanwhile, in 1997 Gelman Sciences was sold to Pall Corp., a conglomerate headquartered in East Hills, N.Y. – the local operation became part of a subsidiary, Pall Life Sciences. In 2007, Pall closed the manufacturing plant on Wagner Road, where the contamination originated. However, a groundwater treatment facility continues to operate there, as part of the court-ordered cleanup effort that’s directed by the state Dept. of Environmental Quality.

In late 2008, Pall asked to revise terms of the consent judgment. A proposal was brought forward by the company in 2009 – in May of that year, the state held a public meeting to discuss the proposal. That was the last time the state has held a public meeting on the topic, until the March 30, 2011 meeting at Abbot Elementary.

The MDEQ rejected Pall’s proposal in June of 2009. But later that year, Washtenaw County Circuit Court judge Donald Shelton ordered the two parties to work together and present a proposal for a third amendment to the consent judgment.

There was no opportunity for public input during the period when Pall, MDEQ and the court were discussing possible changes to the consent judgment, and those discussions were not held in public. Roger Rayle, a Scio Township resident and leader of Scio Residents for Safe Water, has been speaking out against this process for months. Rayle, who is also a member of the county’s Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD), alerted county commissioners about the situation at their Feb. 3, 2011 working session. At the time, he told commissioners, “If it doesn’t involve your district now, it will.”

In early March of 2011, Shelton ordered a change in the terms of the consent judgment, including some aspects that had previously been rejected by the state. [.pdf file of March 2011 amendment to the Pall-Gelman consent judgment. Additional related documents are available on the CARD website. The MDEQ also maintains a website specifically for information related to the Pall-Gelman site.]

Pall Consent Judgment

Much of the March 30, 2011 meeting was spent providing background on cleanup efforts and describing elements of the amended consent judgment.

Mitch Adelman of the Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality’s remediation division told the crowd that the basis for making amendments to the consent judgment stems from Part 201, Section 2a of the state’s Natural Resources & Environmental Protection Act (NREPA). The relevant part of Section 2a states:

(3) Notwithstanding subsection (1), upon request of a person implementing response activity, the department shall approve changes in a plan for response activity to be consistent with sections 20118 and 20120a.

What this means, Adelman said, is that the MDEQ is required to approve changes to legal agreements that meet the requirements of Part 201, as amended. When the MDEQ rejected Pall’s proposed changes in 2009, he said, the company went to court to get it approved, claiming that its plan met state requirements. Adelman said the court has made several rulings in connection with this particular cleanup effort, and “frankly, some of the rulings haven’t been favorable to us.”

The MDEQ had rejected the plan in 2009 for several reasons, Adelman said. The proposal lacked an adequate monitoring plan and contingency plan for dealing with the plume’s possible spread, and there was uncertainty about both the plume’s migration pathways and its current location.

The state’s primary concerns related to protecting of Barton Pond – where the city of Ann Arbor gets 80% of its drinking water – as well as protecting nearby residential wells. There was also the potential that dioxane standards might be changed. Adelman said there’s information from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that might result in lowering the state’s current standard of allowing up to 85 parts per billion (ppb) of 1,4 dioxane in drinking water – which in turn could result in a stricter cleanup requirement. [By way of comparison, when the local 1,4 dioxane contamination was first discovered in the 1980s, the acceptable level in Michigan was just 3 ppb.]

Other concerns cited by Adelman were: the general protection of public health, safety, welfare and the environment; the proposal’s enforceability; and financial assurance from the company that they’d be able to carry out the cleanup to completion.

Adelman and Sybil Kolon, MDEQ’s project manager for the Pall site, described some of the changes made in the amended consent judgment. They include:

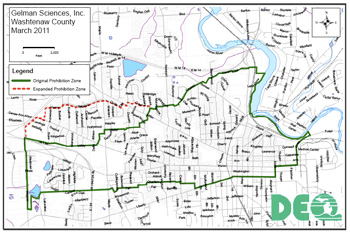

Map of expanded prohibition zone, where residents are prevented from drinking well water that might be contaminated by 1,4 dioxane. The green line indicates the previous area in which residents are prohibited from drinking well water. The red dotted line indicates the expanded zone. (Links to larger image.)

- Expansion of the so-called “prohibition zone.” This is an area where higher levels of 1,4 dioxane are allowed – up to 2,799 ppb – and where property owners are banned from using wells for drinking water. Because property owners in the zone can’t use their wells, they are required to hook up to the city water and sewer system, if they aren’t already connected. Pall covers only part of that expense. The zone is expanded to the north of the current boundary into the Evergreen subdivision area in Ann Arbor. [.pdf of expanded prohibition zone]

- Negotiation of deed restrictions on properties in certain areas outside the prohibition zone, in locations where 1,4 dioxane has been detected. The deed restrictions, to be negotiated between Pall and the property owners, would prevent the use of well water on those properties.

- Installation of additional groundwater monitoring wells by Pall to define and monitor the plume.

- A reduced rate of groundwater extraction by Pall at several locations, but with continued treatment and discharge to the Honey Creek tributary. The groundwater extraction can be terminated with MDEQ approval. Five active extraction wells east of Wagner Road will be decreasing their extraction rate from 500 gallons per minute (gpm) to 300 gpm. Twelve extraction wells west of Wagner will decrease their rate from 675 gpm to about 400 gpm.

- Continued monitoring by Pall of groundwater contaminated with 1,4-dioxane that exceeds the generic residential cleanup criterion of 85 parts per billion, until Pall can demonstrate the remaining groundwater contamination does not pose an unacceptable risk to human health, safety, welfare or the environment, now or in the future. There are 120 monitoring wells west of Wagner Road – of those, 88 are tested annually, 19 are tested semi-annually, and 13 are tested quarterly. East of Wagner, 107 monitoring wells are in place – 23 tested annually, 23 tested semi-annually, 53 tested quarterly, and 8 tested monthly. [.pdf map of monitoring well locations]

The previous consent judgment required full cleanup.

Dioxane Plume: Q&A

Over the course of the three-hour meeting, residents who attended asked a range of questions about the contamination and cleanup. Here’s a summary of the Q&A.

What’s the process of identifying wells that need to be “plugged” in the prohibition zone?

Kolon explained that some homes that are now a part of the city, located west of Maple Road, were originally in Scio Township – in the past they were not hooked up to city water. Subdivisions were platted in the 1920s, with homes built in the 1930s. Pall will survey those properties, she said, to check if wells are still in use. It won’t be a forced inspection, she added – they hope people will voluntarily allow the inspections, which Kolon said she would oversee. If property owners in the prohibition zone know of other wells that haven’t yet been plugged, they should come forward. She conceded that the process hasn’t gone as smoothly as they would have liked.

Who pays for wells to be plugged and homes hooked up to city water and sewer?

Kolon said it’s the state’s position that Pall should pay. But the company has asserted that if a well hasn’t been used for a certain period of time, it shouldn’t be their responsibility to plug it. The state will nevertheless ask Pall to pay for plugging all wells, Kolon said. “We hope we won’t have to go to court about that.”

A resident noted that Pall is paying only to hook up homes to city water service – the property owners have to pay for sewer hookup. “So what kind of deal is that?” he asked. “Sounds like Pall’s got us by the balls.” [The properties would also be annexed to the city of Ann Arbor, which means that property owners would pay Ann Arbor taxes – higher than taxes in the township.]

Kolon replied that at some point, those homeowners would have to hook up to the city’s water and sewer system anyway. State law requires that Pall pay only for the water service hookup.

Who’s monitoring the Pall-Gelman site to ensure they aren’t continuing to contaminate the water?

The company stopped using 1,4 dioxane in 1986, Kolon said. Now, there’s no manufacturing at all at that location.

What’s the status of monitoring the plume’s possible migration north, to Barton Pond?

Kolon said the MDEQ believes there will be adequate monitoring wells in place to detect possible migration. If monitoring wells to the north detect water with more than 20 parts per billion of 1,4 dioxane, then the company must investigate the situation, and possibly conduct a feasibility study to determine how to address the contamination.

A crowd gathers at Abbot Elementary School for a March 30, 2011 public meeting on the Pall 1,4 dioxane plume.

When a resident questioned the wisdom of having the company that’s responsible for the contamination also be responsible for monitoring it, Adelman said the MDEQ is overseeing the monitoring process. In the past, when split samples have been analyzed by both the company and the state, the results have matched up, he said. In response to another question, Adelman said there’s been no evidence that Pall has hidden results from a certain monitoring well.

Vince Caruso, a member of the county’s Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD), said that they’ve discussed at CARD meetings the fact that there are competing analyses of the direction of water flow toward Barton Pond. A Michigan State University study leads them to believe the flow could move to Barton Pond – and if it moves too far, it may be too hard to contain, he said. Caruso also was concerned about contaminated groundwater getting into the basements of homes.

Adelman said the state shares that concern about Barton Pond – that’s why there’s a monitoring plan and wells in place, he said. Caruso indicated that it’s not reassuring to see the prohibition zone extended to the north.

Mike Gebhard, an environmental analyst with Washtenaw County, pointed out that not enough is known about the area’s geology to determine how the plume might spread. Originally it was thought that a protective layer of clay would prevent the plume from spreading east, but that didn’t stop the migration of contaminated groundwater.

Gebhard also noted that the monitoring wells on the northern boundary of the prohibition zone are – at their closest – 1,000 feet apart from each other, and sometimes much farther apart than that. It’s not a tight monitoring network, he said. He also observed that there’s no contingency plan in place if cleanup efforts fail and migration of 1,4 dioxane continues to Barton Pond.

How are residents notified that their homes are in the prohibition zone?

Over 4,000 parcels are located in the original prohibition zone, and neither Pall nor the state were required to contact each residence individually, Kolon said. The same is true for the roughly 400 parcels in the expanded zone. Notices about public meetings are published, but there are no direct mailings to residents.

How are deed restrictions on properties handled?

Deed restrictions, which would prohibit the use of wells for drinking water, will be negotiated between Pall and the property owner, Kolon said. The MDEQ is not involved. If a property owner doesn’t agree to Pall’s offer, it’s possible that the company could take the property owner to court to mandate a deed restriction.

How much 1,4 dioxane is in the plume?

State officials said it’s difficult to say how much wastewater was released over the years, and how much 1,4 dioxane remains underground, or where exactly it’s located. The amount of acceptable levels of 1,4 dioxane has also changed – when the contaminant was first discovered in local drinking water, the state’s criterion for acceptable levels was 3 parts per billion (ppb). That level has been raised to 85 ppb. A much greater geographic area contains 1,4 dioxane in levels below 85 ppb, but the state can’t require Pall to remediate those lower levels. And in the prohibition zone, up to 2,799 ppb is allowed. There are currently pockets where levels are higher levels than that – in the 3,000 ppb range. Those areas are being remediated.

What’s the difference between mass removal and full cleanup?

Full cleanup means decreasing the level of 1,4 dioxane to 85 ppb, Adelman said. For mass removal, there’s no strict standard, he said – Pall will continue to extract contaminated water, treat it, then reinject it into the ground or into the Honey Creek tributary. In the prohibition zone, up to 2,799 ppb of 1,4 dioxane is allowed in the groundwater. Over time, concentration levels have decreased in many areas, Adelman noted.

He clarified that “mass” refers to actual 1,4 dioxane. Kolon added that to date, 64,000 pounds of 1,4 dioxane have been removed from groundwater.

How much 1,4 dioxane remains underground, and how will Pall or the state determine when cleanup is complete?

When asked how much 1,4 dioxane is left, Kolon said they don’t know. Adelman noted that Pall has already removed more 1,4 dioxane than they originally predicted was underground.

There are 17 active extraction wells, from which Pall is removing contaminated water, treating it and reinjecting it into the ground or into a Honey Creek tributary. All extracted water is treated using ozone and hydrogen peroxide to destroy most of the dioxane, according to Kolon. The water that’s discharged to the Honey Creek tributary contains a monthly average of 7 ppb. Extraction wells are tested monthly. However, despite the extraction, the plumes are as big as they were roughly 15 years ago. And under the amended consent judgment, the amount of extraction will decrease.

Pall has cleaned up a lot, Kolon said, but a lot has migrated – “it moves wherever the groundwater takes it.” At some point, though, Pall will determine that they’ve removed enough 1,4 dioxane so that the plume won’t expand, and they’ll ask the state for permission to stop. If the state grants that permission, Kolon said, Pall would still be required to continue long-term monitoring for at least 10 years, and probably longer.

What happens if your property is outside the prohibition zone, but you have water with over 85 ppb?

Adelman said the county wouldn’t permit you to drill a well under those circumstances. “So those people are screwed,” the resident replied.

Why didn’t the state refuse to negotiate a new plan with Pall?

Adelman said that if they had denied the plan again, Pall would have asked the court to force the state to adopt it – and the company could have won. It was the collective opinion of MDEQ staff and a representative from the attorney general’s office, he said, that the court could impose something worse than what the state could negotiate. What they got isn’t perfect, he added, but it’s better than it might have been.

In the worst-case scenario, when will the contamination reach the Huron River?

Mike Gebhard, an environmental analyst with Washtenaw County, calculated that it could take 10-15 years or less. He said there aren’t enough monitoring wells in place at this point to get an accurate picture of where the flow is headed, and how fast.

What happens if Pall goes out of business?

Until this latest amendment to the consent judgment, there were no provisions for that possibility, Kolon said. Now, the state is getting a corporate guarantee from Pall, based on a five-year projection of their costs to operate the cleanup. Pall is doing quite well, she noted, but if things change and the company goes out of business, the state would get funds to run the cleanup. [In early March 2011, Pall reported a 52% increase in second-quarter earnings to $75.7 million, and a 15% jump in revenues to $645.2 million.]

What happens if the state reevaluates and lowers the current acceptable level of 1,4 dioxane, which is set at 85 parts per billion?

Adelman said the new consent judgment has a provision that allows the state to reopen that issue. If lower standards are put in place – when the 1,4 dioxane was originally discovered in this area, the state limit was 3 ppb – then the MDEQ could petition the court to require Pall to clean up groundwater to that new level, Adelman said. However, there’s no guarantee the court would agree to that change.

Could Pall ever be required to install equipment in the city of Ann Arbor’s water treatment plant that would remediate 1,4 dioxane?

Kolon said there have been some discussions of that possibility in the past. Adelman added that the state hasn’t pushed for it because it might be interpreted as accepting a scenario in which the city’s water source at Barton Pond gets contaminated.

As a taxpayer, why should I be happy about this?

Adelman said they weren’t saying that people should be happy. The state had to approve a proposal that complied with the law, he said. “Should you be happy? If I were you, I don’t think I would be.” He said he wasn’t going to try to sugarcoat the changes, but that it was the best they could do, given the constraints.

General Public Commentary

In addition to asking questions, several residents who attended the March 30 meeting leveled criticisms against the company, the court and the state, especially related to the process of amending the consent judgment.

Roger Rayle, a Scio Township resident who's been tracking how the state is overseeing Pall's 1,4 dioxane plume cleanup for many years, videotaped the March 30, 2011 public meeting held by MDEQ staff at Abbot Elementary School.

Roger Rayle, who videotaped the meeting, noted that the last public meeting was held in 2009. Based in part on public input from that meeting, Pall’s proposal was rejected by the state. But this time, he said, public input has been ignored. The county’s Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD) meets regularly – those meetings are open to the public – but their input has been ignored as well, Rayle said. Now, without public process, much of Pall’s proposal has been codified. He said he wasn’t blaming Adelman or Kolon personally, but they are agents of the state. The outcome is not good for the state of Michigan, and that’s not good for protecting the Great Lakes, which contain 20% of the world’s fresh water.

Rayle said the fact that Judge Shelton didn’t see all the facts related to the plume is a problem. “It’s not that the foxes are in charge of the henhouse,” he said. “The foxes are architects of the henhouse.”

Pat Ryan, an Ann Arbor resident, told the group that everyone should know how important it is for the community to be vigilant about this situation. Citizens need to be talking to state officials as often as the company does, she said. She noted that Washtenaw County isn’t at the vanguard of regulatory deterioration – “we’re just joining the rest of the state.”

Yousef Rabhi – a county commissioner who represents District 11, an area covering southeast Ann Arbor – told Adelman and Kolon that at the end of the day, they worked for the public. He said it’s incumbent on citizens to elect people at the state level who’ll represent their interests when it comes to issues like environmental protection. Rabhi, who is the county board’s liaison to CARD, urged people to contact their current state officials – it’s important to hold them accountable. When he noted that he didn’t think his district was affected by the plume, someone in the crowd shouted out, “It will be!”

Coda: April 5 CARD Meeting

Rabhi also was among a much smaller group who attended the most recent meeting of the Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD), held on Tuesday, April 5. CARD is a coalition of citizens and local governments – including the county – that’s focused on addressing the 1,4 dioxane problems.

An April 5, 2011 meeting of the Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD). Clockwise from left: Sybil Kolon, project manager with the Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality; Washtenaw County commissioner Yousef Rabhi; Ann Arbor Township supervisor Mike Moran; Mike Gebhard, Washtenaw County environmental analyst; Vince Caruso of the Allen Creek Watershed project; Matt Naud, city of Ann Arbor environmental coordinator; and Gordon Bigelow, Ann Arbor resident. Obscured from view is Roger Rayle, a leader of Scio Residents for Safe Water, and Rita Caruso, who serves on the Ann Arbor environmental commission.

This was the first meeting since news that the amended consent judgment had been signed, though members had known it was in the works. Kolon also attended, and many of the questions posed by CARD members dealt specifically with terms of the amended agreement. Some people at the meeting expressed a certain amount of resignation that, since it was a done deal, there’s very little room for input. Mike Moran, Ann Arbor Township supervisor, noted that nearly every item that’s stipulated in the consent judgment also allows for the possibility of dispute resolution – that means whenever Pall wants to change the terms, they can make that request to the court.

Mike Gebhard, an environmental analyst with the county who led the CARD meeting, opened the discussion by saying they hoped to ask questions of Kolon about the consent judgment and its interpretation, and to get a sense of “where we fit in.”

The Chronicle was unable to stay for the entire April 5 CARD meeting. In a phone interview the next day, Matt Naud – the city of Ann Arbor’s environmental coordinator – said the meeting primarily offered CARD members a chance to ask questions about the consent judgment, since MDEQ staff hadn’t previously been able to talk about the agreement while it was being negotiated. He said Rabhi had suggested that CARD compile a list of all the issues they would like to see addressed, if given the opportunity. That’s an action item they’ll pursue.

For example, in 2009 a consultant hired by the city of Ann Arbor proposed putting two additional wells on the north boundary of the prohibition zone, to provide data that could help determine where the plume is flowing. Those wells aren’t required as part of the consent judgement.

Naud noted that historically, another challenge has been that Pall has greater resources on its side, including well-paid attorneys, while the state relies on MDEQ and the attorney general’s office. At the April 5 meeting, some members discussed the fact that the attorney general’s staff hasn’t been well-prepared when in court to argue for tighter regulation of the cleanup.

CARD plans to continue to meet. MDEQ staff and CARD’s technical group are tentatively scheduled to meet next on April 27 at 9 a.m. at the Washtenaw County Western Service Center, 705 N. Zeeb Rd. Check CARD’s website for confirmation of the meeting date and time.

The video of the whole 3/30/2011 DEQ Public Meeting is viewable on this Youtube playlist: [link]

Some other videos about the Pall/Gelman site are at [link]

Also, just to correct a couple of points in this article… The last time Pall did a calculation of how much dioxane was left about 10 years ago when they figured there was about 80,000 pounds of dioxane left in the groundwater. Since then they have removed much more than this… and refuse to calculate how much is left (or maybe the DEQ hasn’t asked them to like we wanted.)

The size of the plume HAS changed significantly in the last 15 years… most notably because of the discovery of the deeper E unit plume that the company (and the DEQ) chose to ignore from 1993 to 2001, when the one well known to be screened at that depth east of Wagner was left unsampled for over 7 years. If that well, MW-30d, had been sampled all along, the dramatic rise in dioxane contamination in the deep E unit contamination would have been apparent… and maybe contamination and shutdown of the City’s Northwest Supply Well could have been avoided.

Some of that deeper plume now may be heading northerly under the Evergreen area towards Barton Pond where Ann Arbor gets 80-85% of its water. It will be interesting to see if Pall asks to curtail sampling of wells that show this.

As a member of the Allen’s Creek Watershed Group I would have to ask why groundwater moving through the city that flows into homes on a regular basis is not a concern for the regulators. This seems very obvious for many who have asked about basement contamination.

Also Judge Sheldon should hire a Court Master (expert in toxicology and geology) to help understand this complex issue. He can use part of the $5M Pall owes him for not meeting a past deadline. Our state attorney’s office has done a very poor job representing the community. We could use all the help we can get in court.

Additionally some issues not discussed at the meeting are: city construction that pumps water in order to put in foundations has gotten a lot more complicated; what about the solvent effect of this plume on river sediment contamination being liberated to contaminate the river water. Both seem unintended consequences not considered in this very simplistic and unrealistic cleanup plan.

Thank you for the detailed reporting. I can’t believe that it has been over 25 years! Nor can I believe the ‘safe’ level (as if–) has been raised from 3 ppb to 85 ppb, let alone the thousands higher permitted in some.areas, and a creek ? A creek ??!!