Column: Ann Arbor Parking – Share THIS!

It’s budget season for the city of Ann Arbor.

Over the last half decade, Ann Arbor’s annual spring budget conversation has evolved to include a discussion of public parking system revenues.

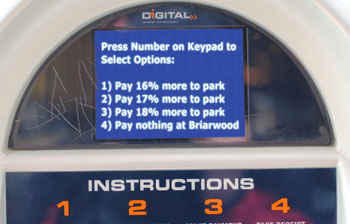

In discussions about parking revenue, it’s been suggested that what the city of Ann Arbor is proposing is the equivalent of a tax on downtown parkers. (Photo illustration by The Chronicle. This is not what Ann Arbor parking meters actually look like. Yet.)

This year is no exception. The city council’s public hearing on the budget takes place at its May 2 meeting, with a vote on the 2012 fiscal year’s budget scheduled for May 16. At that May 2 meeting you’ll also hear the city council discuss revenues from the public parking system. The board of the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority – which manages the city’s public parking system – will meet at noon the same day to ratify its side of a contract renewal.

As likely as any other scenario is an offer from the DDA for the city to receive 17% of gross revenues from the public parking system for each year of an 11-year term. But that offer stands a decent chance of getting rejected by the city council. The city’s last bargaining position was 18% for a 10-year term and multiple three-year renewals.

Public parking revenues were already part of council deliberations at a city council budget work session on April 11, when city administrator Roger Fraser had given a dress rehearsal of his budget proposal. At the work session, councilmembers and Fraser played out a scene, in which councilmembers offered up questions to Fraser to elicit this conclusion: If the city does not extract enough revenue from the city’s public parking system, the city will need to lay off additional police or firefighters – four this year and two the following year.

The scene was reprised on April 19, when the city’s budget was formally premiered. The budget did not appear to depart in significant ways from the department-by-department budget impacts that city managers have presented to the council at a series of work sessions since the beginning of the year.

On April 19, it was the city’s CFO Tom Crawford (later in the meeting to be appointed interim city administrator) who played the role of the “numbers guy.” So it was Crawford who gave the recommendation in response to councilmember prompts: Without sufficient revenue from the public parking system, he would recommend laying off an additional four public safety officers. That’s in addition to the five police officers, three other non-officer positions in the police department, and five firefighters who are already slated for layoff.

Councilmembers Christopher Taylor, Carsten Hohnke, Marcia Higgins, Stephen Kunselman and mayor John Hieftje played starring roles in their portrayal of elected officials that evening. But more to the point of this column, I wonder who the city council’s imagined audience is for this sort of theater? Presumably it’s for an audience that pays the price of admission. But in Ann Arbor, it’s an audience that typically doesn’t pay much attention: the city’s shareholders.

Yes, that’s exactly the word I want. Shareholders.

I want that word in order to give myself some room to think about calling the voting public “shareholders” instead of “voters” or “residents” or “citizens.” It’s not because Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder campaigned on a slogan saying he’d run government like a business, and has continued that kind of talk since taking office.

It’s because I think a different word, “stakeholder” – as it’s used in Ann Arbor’s public discourse – has lost its original contrastive meaning. It was coined originally not as just a shorter way of saying “people who have a stake in this thing.” It was coined almost a half-century ago specifically to contrast with the term “shareholder.” And I think it’s worth reminding ourselves of that contrast.

Shareholders, Stakeholders

Back in 1963, the term “stakeholder” was coined in an internal memo at the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International). Stakeholders included “shareowners, employees, customers, suppliers, lenders, and society.” At the time, elevating those groups in importance was a fairly radical challenge to the prevailing view in business circles that shareholders are the only stakeholders that truly matter when company mangers make choices.

Writing in his 2003 book “Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets of Lasting Value” William George, a professor of management practice at Harvard Business School, describes the stakeholder model of a business and how he learned about it:

… the criterion for measuring the success of our leaders should be how well they serve everyone that has a vested interest in the success of the enterprise. This is known as the stakeholder model. I was first introduced to it by Henry Schacht, the CEO of Cummins Engine, at a 1970s conference on corporate responsibility. Schacht outlined the stakeholder concept of serving all those who had a stake in the enterprise:

- Customers

- Employees

- Shareholders

- Suppliers

- Communities

… Serving all your stakeholders is the best way to produce long-term results and create a growing, prosperous company.

Schacht’s predecessor and mentor, J. Irwin Miller, one of the authentic leaders of this era, initiated the stakeholder model. Miller had a keen appreciation of the importance of building a motivated employee based and a thriving community in the company’s small hometown of Columbus, Indiana, in order to serve its customers, its suppliers and its shareholders. Although Miller was not widely known outside business circles, his picture once appeared on the cover of Fortune magazine during the Watergate era with the caption, “This man should be President,” noting that the values and character Miller represented were precisely what America needed in its leaders.

Many of my elementary school classmates in early 1970s Columbus, Ind. had parents who worked for Cummins – so they were Cummins stakeholders. In 1957 the Cummins Foundation had paid for architect Harry Weese to design the Lillian C. Schmitt elementary school, where I attended kindergarten through sixth grade. So even though my own family did not have a direct connection to Cummins, we lived there – so we were stakeholders, too, and we derived a specific return from our stake in Cummins.

I think it’s easy for progressive Democrats to look at the example of Cummins Engine and conclude that yes, that’s what corporate responsibility should be – decisions should be made by considering not just shareholders, but also stakeholders.

What happens, though, if we try to apply the idea of a stakeholder model of business to our local government? Who are the shareholders? Who are the other stakeholders besides the shareholders in a local government? It makes some kind of sense to think that among the shareholders are property tax payers – but not all of them get to vote. So perhaps it is simply voters who are the best pure analog to shareholders.

If we believe in a stakeholder model of business, and think it’s appropriate to apply a business model to local government, that leads to a somewhat startling conclusion: We should expect city management decisions to be based not just on the short-term interest of voters.

One way to reject that conclusion is to reject the premise that government should be run anything like a business. But here in Ann Arbor, we do appear to believe in government as a business – inasmuch as the term “stakeholder” is sprinkled easily through the talk of residents, as well as our appointed and elected officials.

From the recent resolution adopted by the city council, which tasked the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority with leading a process to explore alternate uses of a limited set of city-owned downtown surface parking lots [emphasis added]:

- Hold meetings with business and community stakeholders to determine professional assessment of the Parcel-by-Parcel Plan

For some folks, that language was not inclusive enough of “the public” and two additional clauses were strengthened with the word “robust” – which provoked some debate among councilmembers. From the resolution that was eventually passed:

- Solicit robust public input and conduct public meetings to determine residents’ Parcel-level downtown vision

…- Solicit robust public input and confirm the extent of community consensus for the Parcel-by-Parcel Plan through public meetings and surveys

A different way of including “the public” or “the people” would be to prefix “shareholders and” anytime the word “stakeholder” is invoked. And once we’re speaking the language of “shareholders and stakeholders,” then we have a way of talking about different points of view that’s closer to neutral than “the people” and “special interest groups.”

So that’s what I’d like to do in considering the question of how revenues from the public parking system should be spent.

Parking System Revenues: Background

The conversation about revenues from the public parking system is one that the city of Ann Arbor has successfully framed as a question of control: Should it be the city council or the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority that decides how to spend the revenues from the public parking system?

The Ann Arbor DDA is a tax-increment finance district, formed under the state’s Downtown Development Authority Act 197 of 1975. The DDA does not levy property taxes directly, but rather “captures” them from other taxing authorities. The DDA does not capture the entire tax on a property – it captures just the tax on the difference (the “increment”) in the baseline value and the value of improvements to the property. The DDA does not capture taxes on the appreciated value of the property.

While a downtown development authority formed under Michigan’s state statute is a “public body corporate” that can sue and be sued, a DDA is not empowered by state statute to run a public parking system.

But since 1992 it has been the DDA that has managed the city’s parking system by contractual agreement with the city. The shift of responsibility from the city to the DDA was motivated by the fact that some of the city’s parking structures had fallen into such a state of disrepair that they needed to be demolished or dramatically renovated. Two examples are: (1) the deck at Fourth & Washington – demolished and now rebuilt; and (2) the deck at First & Washington – demolished, with the parcel waiting for developer Village Green to finalize its $3 million purchase agreement, for a construction start this summer on Ann Arbor City Apartments, a nine-story residential project that includes a parking deck on the first two floors.

Skipping ahead to 2005, in that year the city and the DDA revised a parking contract that they’d signed in 2002, so that in addition to a payment to the city’s street repair fund, the city would receive $1 million per year from parking revenues in “meter rent.” As part of that 2005 agreement, the city had the option of requesting an accelerated payment of $2 million per year – as long as the total amount paid to the city did not exceed $10 million.

Somewhat predictably, the city requested the maximum per-year payment of $2 million in each of the first five years, and then asked to renegotiate the contract. At public meetings over the last year, DDA board member Sandi Smith (who’s now also a city councilmember) has stated that there was no doubt in her mind in 2005 that the city would max out its allowable payment, then ask to renegotiate.

Even without negotiating the contract, the Ann Arbor DDA elected last year, in 2010, to transfer $2 million to the city that was not required under the terms of its contract with the city. The city administrator’s proposed budget last year had not factored in the $2 million, and had proposed police and firefighter layoffs. In that drama, the city council portrayed itself as hard-working heroes who used the additional “unexpected” revenue to avert layoffs in the police and fire departments.

That allowed the mayor last year to campaign for re-election on a perfect record of never having laid off a police officer in the course of a decade in office. Up to this year, the reduction in Ann Arbor’s police force has been achieved through attrition and early-retirement buyouts. In the last decade, the city council has never allowed layoffs to be a consequence of collective bargaining that did not achieve desired savings.

Parking System Revenues: Control, Money

The recent negotiations over the use of public parking revenues have been handled by committees from the city council and the DDA board. In concept, those committees originated in January 2009. But discussions between them did not become public until the summer of 2010.

The discussion about the contract revision can be divided into broad categories: (1) control; and (2) money.

For the first category, the two committees have settled on contractual language that includes the following key points, which are not included in the current contract:

- Rate Setting: DDA would have the authority to set parking rates, with certain requirements on public input before rate changes would be changed. Currently the city council can veto rate changes – that veto would not be a part of the new contract.

- Geographic Area: The geographic area where the DDA will have authority to manage the parking system would be precisely defined. The motivation behind this language is to prevent situations like one in 2009, when the city enacted a plan to install meters in additional locations where the DDA felt meters were inappropriate for a variety of reasons.

- Communication: A standing committee with representatives from the DDA and the city would be formed to coordinate parking enforcement activity with rate policies. Regular reporting by the city to the DDA on enforcement and street repair activities would also be required.

For the financial part of the contract, the committees have moved away from a collection of separate payments to a percentage-of-gross arrangement. The separate payments that are currently reflected in historical practice, if not under the terms of the contract are: (1) meter rent – $2 million per year; (2) street fund – currently $840,000 per year with a formula-based increase; and (3) revenue from 415 W. Washington and Fifth & William surface parking lots – $170,000 per year.

The two negotiating committees have tried to arrive at a percentage-of-gross number that would roughly approximate (over the life of the contract) the city’s withdrawals from the public parking system in recent years.

Earlier this month, the positions of the two bodies on the percentage of gross public parking revenues that the city should withdraw had reached an impasse of sorts. The city council’s position, as reflected by its committee, was 16% in the first two years of a 10-year contract and 17.5% in remaining years – the 16-16-17.5 scenario. The DDA’s committee, after going back to the full DDA board on two occasions, had raised its offer to 16% in all years of a 10-year contract – a flat-16 scenario.

By way of orientation to the scale of the parking revenue fund, its projected revenues for FY 2012 are around $16 million. Fixed costs for the DDA’s subcontractor, Republic Parking, come in at around $7.4 million. The DDA typically allocates a little over $2 million per year to its maintenance program for the parking decks. Debt service paid out of the parking fund and a transfer to the DDA’s bond fund totals around $4 million. An annual grant to fund the go!pass program for getDowntown takes another $0.5 million.

The DDA’s position is based on the financial stress the parking fund and the entire organization would be under, if the DDA were to agree to the higher percentage-of-gross figures. To relieve pressure on the parking fund, the DDA has already deferred its maintenance schedule for the decks and has decided to allocate a portion of the bond payments for the Fifth Avenue parking deck from its TIF fund. On a flat 17% scenario, the parking fund would show a balance of -$157,000 in FY12 and -$327,000 in FY13.

At the April 19 city council meeting, councilmembers instructed their committee to go back to the DDA, not with support for the committee’s prior negotiating position, but rather with an escalated request: 18% of gross revenues every year.

This kind of “negotiating” strategy leaves room to wonder if the city’s collective bargaining conversations with its unions are equally bizarre – where the city seeks to increase the gap between established positions, instead of closing it.

But leaving aside for a moment the city’s schizophrenic negotiating strategy, it’s worth thinking about the basic concept behind a percentage-of-gross arrangement as opposed to some kind of flat payment.

The idea is that the interests of the DDA and the city are aligned under such a scheme – because revenues to both organizations increase or decrease in parallel. And there’s no built-in check on rate increases – on a percentage-of-gross arrangement, both the DDA and the city have an interest in seeing parking rates be set as high as possible without causing demand to decrease.

Otherwise put, with respect to public parking system revenues, the percentage-of-gross arrangement gives the city and the DDA a parallel stake in the system.

Parking System Revenues: Shareholders, Stakeholders

The city and the DDA have historically conceived the issue of public parking revenue as one about organizational stakeholders – the city of Ann Arbor versus the DDA.

Portraying the question as the competing interests of organizational stakeholders works to the city’s advantage for at least two reasons.

First, many Ann Arbor residents have a built-in skepticism of the DDA. Why? Because its board members are appointed, not elected. Of course, it is elected officials who appoint DDA board members – nominations by the mayor and confirmation by city councilmembers. But that additional layer of accountability makes some Ann Arborites uneasy. It’s that audience to which councilmember Stephen Kunselman was playing when he said at the council’s April 19 meeting that he didn’t think there was a single Ann Arbor resident who was interested in giving the DDA more control over the city’s public parking system.

Second, if the conversation is defined as being fundamentally about the competing interests of two stakeholder organizations, then it’s fair to ask: Which organization’s financial health should be given priority – the DDA’s or the city’s? It’s on that basis that much of the conversation unfolded at the city council’s April 19 meeting. City councilmembers were keen to portray the city’s undesignated fund reserve as taking priority over the DDA’s fund balances.

But what if we took very seriously the idea that this is not a question just about two organizational stakeholders, but rather one about a whole range of stakeholders – as well as shareholders?

I’ve made this point before, in a column written last year:

The question of how excess parking revenues should be spent is a pure public policy question, that is not necessarily contingent on who gets to make the public policy choice. But the negotiation between the city and the DDA has focused the public’s attention on the “who” of the policy choice, instead of the choice itself. The “who” making the choice is in some sense a surrogate for how we feel about the choice itself.

With respect to decisions about how public parking revenues are spent, the shareholders include at least the voting public in Ann Arbor. And if the decision is made based purely on the short-term interest of the shareholders, then excess parking revenue would likely be invested in the city’s general fund to pay for expenses like administration, the city attorney’s office, parks, police and firefighters. Certainly, I think it’s fair to say that most councilmembers perceive that this is the majority view of the shareholders.

But if we adopt a stakeholder model of governance, then it’s not just the short-term voting public’s interests – i.e., the interest of shareholders – that elected representatives should consider. On the stakeholder model, they should consider the long-term interests of the shareholders as well as the interests of the stakeholders.

So who else, besides the voting public, count as stakeholders in the public parking system? It’s not hard to come up with examples: businesses located downtown whose employees want to drive to work; the employees of those businesses; retail businesses whose customers want to drive and park downtown; downtown property owners who want to be able to lease their buildings to tenants who desire parking availability; downtown residents who want to own a car and store it close by for occasional use.

The point here is not to try to make an exhaustive list. It’s simply to point out that the decision about how public parking system revenues are spent should include at least all these stakeholders. And if we really believe in a stakeholder model of governance, then we can’t simply say: Well, yes, all those groups are also stakeholders with legitimate interests, but ultimately, the short-term interest of shareholders trumps that of mere stakeholders.

At a March 28 meeting of the council and DDA committees, Roger Hewitt, a DDA board member, identified downtown parkers as a group of stakeholders for which the DDA has historically been an advocate. Over the last several months of committee meetings, Hewitt has displayed increasing frustration with the fact that the DDA’s position as a lobbyist for downtown parkers puts it in a situation where it cannot succeed – because the city’s eye is only on the short-term revenue from the system.

Hewitt himself is a downtown business owner – of Red Hawk Bar & Grill, Revive and Replenish. On March 28, he pointed to a contrast between his employees, who must pay for parking, and the beneficiaries of the parking revenue when it’s withdrawn from the public parking system by the city. The beneficiaries, Hewitt said, are city workers who enjoy salary and benefits far exceeding what his own employees could hope to achieve. Hewitt echoed the same sentiment on April 27, at a DDA operations committee meeting [officially known as the "bricks and money" committee].

Translating Hewitt’s point to the language of shareholders and stakeholders: While city employees are certainly stakeholders in the public parking system, so too are downtown employees who pay to park. So part of the conversation about the use of public parking revenue should be about how to balance appropriately the interests of those two stakeholder groups.

As part of that same conversation on March 28, Hewitt’s frustration was evident when he floated a proposal to eliminate the need for an annual battle about the amount to be transferred from the public parking system revenues to the city:

Hewitt’s “Take As Much as You Need” Proposal: Each year the city informs the DDA what dollar amount of public parking revenue it needs for the upcoming year. The DDA sets rates as high as necessary to generate that amount of revenue.

In connection with that proposal, Hewitt also raised the specter of signage in parking structures and on parking meters with a pie chart indicating something like “N% of your parking dollar goes to the city of Ann Arbor’s general fund.”

It’s fair to say that the councilmembers at the table – Carsten Hohnke, Christopher Taylor and Margie Teall – were flummoxed when Hewitt floated that proposal. In scrambling to reject the idea politely, they essentially argued that in spirit that’s what the contract with a percentage-of-gross arrangement was attempting to formalize – the only difference was the need for the city to articulate each year what amount of parking revenue it needed.

The explicit take-as-much-as-you-need idea also received little traction from the DDA board when Hewitt floated it at a March 30 meeting of the DDA’s operations committee. Part of the reason I think it foundered was this: It would have made completely transparent the relationship between parking revenues and the city’s general fund. That’s a political cost the city council is unwilling to accept, because it would highlight the fact that it is a body that lacks discipline.

Discipline

Part of the fundamental concept of a TIF authority like the DDA is that certain tax revenues are not put through the regular budget process of the taxing authorities whose taxes are “captured” by the TIF. This very fact is objectionable to some of Ann Arbor’s shareholders. In his last two city council campaigns – for the Ward 5 city council seat currently held by Carsten Hohnke – John Floyd has raised exactly this issue.

The way Floyd sees it, investments in the downtown should be able to compete with investments elsewhere in the city as part of the regular budgeting process for the city and for the other taxing authorities whose taxes are captured. On Floyd’s view, if the city council (or the Ann Arbor District Library board, or the Washtenaw Community College board, or the AATA board, or the Washtenaw County board of commissioners) sees fit to make investments in Ann Arbor’s downtown as part of their regular budgeting process, then it will do that fair and square.

Historically, the city has elected to contract with the DDA to operate its public parking system – in a way that puts at least some of those public parking system revenues in the same category as TIF capture. That is, public parking revenues are, by contract with the DDA, not all subjected to the regular budgeting process of the city. Instead, decisions about the spending of parking revenues are made outside of the city’s regular budgeting process.

One way of thinking about both TIF capture and contractually-obligated public parking system revenues is that they’re both a way for the city to self-impose a certain discipline on itself. That discipline is essentially to make a long-term commitment to investments in the downtown and in the public parking/transportation system – investments that prioritize long-term value for all stakeholders over short-term value for shareholders. For example, the disciplined approach is one that leads the DDA to invest parking revenue to subsidize bus passes for downtown employees through the go!pass program, which is administered by the getDowntown program.

Imagine a regular budgeting process that asks shareholders to choose between (1) reduced park maintenance and fewer assistant city attorneys; and (2) eliminating free bus rides for employees of downtown businesses. I think that an accurate representation of short-term shareholder interests would favor park maintenance and city attorneys every single time. That would be all the more true if you set it up as a choice between police officers and free bus rides.

And that’s exactly why I think the choice to self-impose this kind of discipline is a good one. The fact is that we as a community have made a choice for this kind of discipline – by establishing a DDA. And the city council in 2005 made an apparent choice for discipline by limiting its use of parking revenue to $1 million a year. One could imagine self-imposing a different kind of discipline – one that would require that we hew to the short-term interests of shareholders. However, we haven’t done that in any explicit way.

The Ann Arbor city council is not, as a group, very disciplined. Instead of living with its choice to limit itself to $1 million a year in parking meter rent, it built into the contract with the DDA the option to withdraw $2 million per year, until it reached its limit. And now the council has decided to take the approach of simply withdrawing as much parking revenue as it can.

A disciplined city council might have opted back in 2005 to say: “Okay, we need to align our labor and budget strategy; if we can’t get the kind of collective bargaining concessions we need from unions for their health care and pension costs, then we’ll reduce staff proportionately based on the cost of those benefits.” It’s only this year that we’ve heard the city administrator take that fairly obvious step.

Instead of exercising discipline, the city council has chosen over the last half decade to avoid layoffs of public safety workers – either by paying for early retirements or by using public parking system revenues to maintain staff levels.

It’s not surprising that they’ve chosen an undisciplined path as a body – some of them are undisciplined individually. To illustrate, last year at the council’s Jan. 19, 2010 meeting, mayor John Hieftje – by the description of two of the mayor’s strongest supporters on the council, Carsten Hohnke and Christopher Taylor – showed “leadership” by choosing to declare publicly that he would be offering a voluntary give-back of 3% of the salary he receives for the job.

That night, Hohnke and Taylor clearly stated their willingness to participate in the 3% giveback, as did some other councilmembers. Except for Sabra Briere, Stephen Kunselman and Mike Anglin, all councilmembers eventually (either that same evening or else at subsequent meetings) seemed to give a public indication that they’d also be participating in the 3% giveback. It turns out that even Briere also wrote a check, but not for 3% – it was for $100, or a bit over a half percent.

On Feb. 22, 2011 – more than a year after the public promises were made – The Chronicle inquired with the city’s financial office about the status of those payments. Not all had paid. But by March 7, 2011, all those who said they’d participate had finally made good on their commitment – it took The Chronicle’s inquiry to get them to follow through. According to city staff, it had been the expectation of some councilmembers that they would be invoiced with an incremental payment plan. And apparently when they didn’t receive an invoice from the city, they didn’t have the discipline to make the payments on their own.

So far this year, the mayor has not chosen to announce a 3% give-back. So it’s somewhat ironic that the chair of the council’s labor committee, Stephen Rapundalo, has stressed publicly that the city’s firefighter’s concessions made last year were only for the six months remaining on their contract. Under collective bargaining laws, of course, the firefighters continue to work under the contract concessions they agreed to. Councilmembers so far have not expressed any eagerness to continue their voluntary 3% give-back through this year.

Political Reality

The stark reality of the politics concerning public parking revenues is that the decision will be made as a negotiation between the city council and the DDA – which will likely not involve any deep discussion of stakeholders, shareholders or discipline.

At the Monday, April 25 meeting of the two committees from the DDA board and the city council, those around the table reflected on the city council’s performance a week before, on April 19.

That was a meeting where the council had voted to direct its own negotiating committee to escalate the city’s expectation of percentage-of-gross parking revenue payments – upward from the city committee’s previous position to a flat 18% in all years of a 10-year contract. That direction came after the council entertained an even higher percentage-of-gross public parking revenues for use in the city’s general fund – 19%.

On Monday morning, DDA board member Roger Hewitt thanked Christopher Taylor – because Taylor had been the only member of the city’s committee who had displayed the discipline to vote the committee’s position against the rest of the council. Hewitt pointed out to Carsten Hohnke that Hohnke himself had abandoned the city committee’s position and voted for the amendment of the resolution to 18%, as well as for the resolution itself. Margie Teall had voted against the amendment, but ultimately for the resolution.

Hohnke’s explanation to Hewitt was that he’d argued for the committee’s position – but when it became apparent that the consensus of the council was not aligned that way, he felt compelled to stand with his fellow councilmembers. He characterized his decision as the same one that Teall had made one step later and that Taylor had made two steps later – that very morning, in choosing to accept the council’s direction to continue negotiations based on the 18% figure.

Hewitt expressed concern that it was not just the financial part of the contract that was in doubt. Based on sentiments expressed at the council’s April 19 meeting, he wondered if there was adequate support on the council to ratify the non-financial aspects of the contract – those that involved giving the DDA more control over the parking system it is supposed to manage. Taylor tried to downplay the sentiments that had been expressed by some councilmembers (like Stephen Kunselman) as those of “outliers.”

Taylor suggested to Hewitt that for the non-financial parts of the contract, he could count four votes for sure: the three committee members (Taylor, Hohnke, Teall) plus Sandi Smith, who serves on both the DDA and the city council. Taylor ventured that without wild speculation, one could come up with two more votes, for the six (out of 11 councilmembers) they’d need to ratify the contract.

However, at the DDA’s operations committee meeting two days later, on April 27, Sandi Smith indicated that she felt like nobody really cared about the conversation the DDA was having over the percentage-of-gross figure, because it was going to be “shut down” on May 2 by the council. She doesn’t think there’s sufficient support for the non-financial aspects of the contract for the council to ratify it.

The operations committee also entertained some discussion of the “nuclear option” of dissolving the DDA, to which Carsten Hohnke had vaguely alluded at the April 25 meeting. That allusion came in the context of comments made by DDA board member Russ Collins. Collins noted that if “bombs are thrown over the transom” in order to create political movement, that thinking in cartoon terms, sometimes it’s best to catch them and throw them back. Hohnke told Collins that what Collins might be detecting among councilmembers is this: One could come to the “not irrational conclusion” that there’s an alternative available to provide a better net return.

At the April 27 DDA committee meeting, Leah Gunn observed that if the city wanted to dissolve the DDA it could do that – but Smith labeled that as a false argument. It was not financially realistic, she said. However, back in December 2009, the city’s chief financial officer Tom Crawford told the city council at a budget retreat that dissolving the DDA would result in a net positive to the city’s general fund of $700,000 per year. It’s not more partly because the DDA has committed $0.5 million per year in TIF revenue to help make bond payments on the city’s new municipal center.

In any event, the DDA’s operations committee decided that it would put a resolution before the full board for the noontime meeting on Monday, May 2 to ratify a new parking contract. That contract will include a percentage-of-gross figure of 17% in every year of an 11-year contract, and one 11-year renewal option. The somewhat odd 11-year number corresponds to the currently scheduled lifetime of the DDA, which goes through 2033. Based on the conversation at the operations committee meeting, it appears there could be attempts to amend that proposal at Monday’s board meeting. Hewitt indicated that he’d been led to believe there was enough support on the council to approve the 17% figure.

The DDA’s operations committee stressed that the board’s ratification of the contract on May 2 would be contingent on the city council’s ratification of the entire contract – which it will consider later the same day, at its evening meeting. The newest member of the DDA board, Bob Guenzel, noted that if the city council chose to alter the non-financial language or the financial figure, that would amount to a counteroffer, and would not bind the DDA based on whatever the board had ratified.

In any case, there appears to be growing sentiment on the DDA board that if the city council does not ratify the parking contract in unamended form, it might be best to just let the existing contract run its course. It currently runs through 2015, with a three-year renewal option.

For example, at the April 25 meeting, Collins indicated that he believed running the parking system was actually a distraction to the DDA. He said his understanding was that one of the DDA’s “most politically progressive board members” was content to leave things the way they are. And at the April 27 meeting, DDA board member John Mouat wondered if they’d reached a point where the DDA should just let the city take back the parking system.

On the scenario where the current contract runs its course, the city’s revenue from the public parking system would be $2 million less per year than what it’s received in the last few years – though the city would still receive roughly $1 million per year (the payment to the street repair fund, plus payments from 415 W. Washington and Fifth & William surface parking lots).

But if the council does not ratify the same contract as the DDA on May 2, some councilmembers reportedly feel they have another option that stops short of dissolving the DDA. That option would be to simply transfer the funds from the DDA to the city as part of the budget resolution that council will approve on May 16.

In 2007, the city council amended the DDA’s budget using a simple resolution – but on that occasion, the change did not result in a transfer of funds. If the council did undertake a fund transfer, it would sure be interesting to see what happened next. On that kind of scenario the financial transaction would still need to be effected by the DDA. The DDA maintains its own funds in its own bank accounts.

The DDA’s board chair would need to sign the check. And it’s a check that would need to be endorsed, ultimately, by a majority of the city’s shareholders.

Just spent a very quick 2 days in Ann Arbor where I was going to spend some time downtown and work from either the workex or a coffee shop. The parking pushed me away. I had an early breakfast downtown and parked curb side– spend $1.20 to park legally for one hour. Parking garages are only $0.30/hour less. So to park for an 8 hr day downtown you’re looking at $7.20 in the garage or more on the surface. After my hour, I went outside downtown, parked for free, and those businesses were patronized.

I am “grossed” out by the statement that maintenance is being deferred on the parking structures. How much maintenance, and on what structures?

Are we going to see these structures start to deteriorate – again?

Re: [2] “How much maintenance [is being deferred], and on what structures?”

Not sure which structures. In their discussions of this issue, which we’ve reported, DDA board members have described the maintenance to be deferred as non-essential maintenance: painting and the like. Maintenance to be deferred is not supposed to include items like the deck washdowns, which are essential to remove the brine from winter, which can lead to accelerated deterioration of the concrete. The maintenance to be deferred has been vetted with Carl Walker, Inc., the DDA’s parking structure engineering consultant, who devised the current maintenance schedule.

But to my mind, maintenance is another issue of “discipline.” In a different draft of this column, maintenance was the highlighted theme, and it was to feature lead art of my broken bicycle front fork. I’d noticed noodling and grabbing for several months and had attributed it to worn brake pads, which I replaced myself. I talked myself into believing that I’d achieved some improvement, even though the problem persisted. Then, as I was braking to a slow stop, I lost about two feet of altitude, as the aluminum fork simply broke. I was lucky I was not bombing down Liberty and trying to make an aggressive stop. If you’ve ever pre-scored an aluminum beer/soda can and torn off the whole top, you’re familiar with the phenomenon of the crack getting to a certain length, then the aluminum basically just “tears.” So was that a case where a failure to perform basic maintenance lead to catastrophe? Maybe not — but if I’d taken the bike into a shop and described the problem, a test ride by a professional mechanic who looks at “bike metal” every day, would have had a decent shot at spotting the crack that led to failure.

To me, that seemed to illustrate more the idea of “trust a pro” as opposed to “be disciplined in your maintenance.” So it was shareholders and stakeholders that received prominence in the column.

I think it’s a pretty easy slide from “we’re deferring transfers to the maintenance fund, but not deferring any maintenance” to “we’re only deferring non-essential maintenance” to “we’re deferring essential maintenance, but only for a little while” to “we’re not doing any maintenance.” We’ve already gone from the first to the second.

[It took me till now to parse Cahill's "grossed" out joke. I assume other readers did that mental computation faster.]

Speaking of maintenance, Tom Crawford’s projection of a $700,000/year benefit to the city if the DDA is dissolved likely assumes no money for maintenance of the parking system.

Awesome post, Dave. I’ve read several accounts of this battle at AnnArbor.com as well as at the Chronicle, but it always seemed to me like just a turf war that I didn’t have any particular stake in. This is the first account I’ve read that really helped me understand why it should matter to me as a citizen.

“According to city staff, it had been the expectation of some councilmembers that they would be invoiced with an incremental payment plan. And apparently when they didn’t receive an invoice from the city, they didn’t have the discipline to make the payments on their own.”

It’s called weaseling out of a public promise. I’m not surprised–it’s pretty much par for the course with several members of council.

Several months ago I noticed rusted risers on the stairs at one of the structures – I think it was my favorite, the cute structure at Fourth & Washington.

I gather that rusted risers are deliberate. This is definitely Not A Good Sign.

In my opinion, the 3% giveback idea was political grandstanding in any event. Councilmembers do not make a large stipend (though the Mayor’s salary is more substantial) and the amount is much smaller than most full-time city employees, especially considering that there are no benefits associated with the position. Certainly, such payments would have no more than a symbolic effect. If a councilmember wants to make a donation to the city, that is fine, but there was a somewhat coercive effect to that whole scheme that I found distasteful.

With regard to CM Briere, I believe that she had already committed to giving the 3% salary raise to charity before the giveback idea came up. I don’t have documentation, however. Mike Anglin was donating his 3% to the Michigan Theater for a time. Again, this is based solely on my recollection.

Great articles on this subject, Dave. We appear to be on a trajectory back to collapsing structures, likely to be followed by even more exploding water mains. It would be great to see the council have more sense, but instead they are acting to confirm skeptical views of politicians. Like many others, part of my thinking about whether to go downtown at any given time includes awareness of parking costs.

In my experience, Ann Arbor parking is dirt cheap compared to most other cities.

However, fortunately for the health of downtown, it is unique compared to other areas of the city and the outlying areas. Because of this uniqueness, I rarely (if ever) find myself making a decision about going downtown vs. somewhere else based on parking.

Some examples:

* The bars and restaurants downtown don’t exist elsewhere.

* If I need to buy groceries, clothes, or hardware, there is no downtown option.

* If I want to attend a concert or a play, downtown/campus is the only option.

This differentation between downtown and the other areas is important to maintaining its vibrancy. I have consistently objected to the AA District Library expanding to the new branch libraries, because it violates this differentiation. I expect that eventually, a combination of the branches and other modern media delivery formats will doom the downtown AADL.