In the Archives: Retrospective Lip Smacking

“In the opinion of very many persons … the word ["student"] signifies a young fellow who smokes, chews, drinks, plays billiards, and perpetrates undignified jokes,” reads an October 12, 1867 article in the University of Michigan student newspaper the University Chronicle. “But as has been said many times, the reputation of students in this respect is owing only to the exceptional few. We hope, for their sake, that they may not reap the whirlwind.”

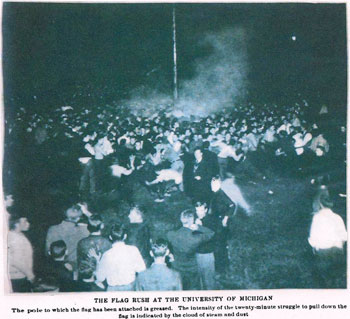

In its August 1909 article on student hazing, Hearst Illustrated magazine published A. S. Lyndon's 1908 photo of students jostling around a flagpole, intent on removing the banner.

The article concerned a developing tradition on college campuses across the country, including UM: an autumn clash between freshmen and sophomores known as “rush.”

The late 1860s appear to be when UM’s tradition of an annual October rush began. The practice would survive for decades despite hospitalizations, expulsions, and several bans against rushing by student government and university officials.

“A rush is a miscellaneous row between two classes, generally freshmen and sophomore, who meet in any of the college halls or grounds,” reads a May 16, 1868 University Chronicle piece on student slang, “and in our own institution is seldom anything more than a good-natured trial of strength between the opponents.”

The article also included slang terms for freshman hazing practices. These included “pumping,” or dousing a frosh in a public water pump, “shaving,” or a less than careful haircut, and “smoking out,” or invading a freshman’s room en masse and lighting pipes till the room was choked with smoke and the new student was nauseated.

Rushing began as more or less impromptu scraps between freshmen and sophomores, as noted in an Oct. 17, 1877 article in the Ann Arbor Register. “One of ‘ye old time rushes’ occurred in front of the post office, on Friday evening, and resulted in the arrest of a sophomore … [the combatants] then adjourned to the campus, and indulged in a rush in front of the Law Building.”

The next year, faculty quashed the practice. “One by one our privileges are taken from us,” moaned an Oct. 26, 1878 article in the student newspaper The Chronicle. “First it was hazing, next horning, [a surprise night assault with noisemakers] and now it is rushing. Yes, nocturnal rushing has been ‘sat down upon.’ An edict from the faculty forbids this gentle sport, even upon the campus, our own territory.”

The article continued, “The ‘peelers,’ [police]* backed by this authority, are getting saucy, and have the courage to display their ‘billies’ in open daylight. Truly we are degenerating.”

The ban held for the following year. “The old-time rush is gone forever,” mourned a May 3, 1879 article in the University Chronicle. “Last year there were indications of a revival of the time-honored custom, but the new regime has extinguished all such indications and we hear no more of the contest of the classes.”

Over the ’80s and ’90s, impromptu rushes continued off campus. The October 12, 1889 issue of the student newspaper the Michigan Argonaut registered its disapproval:

It has been the custom of late years to frown upon the ‘barbaric freshman-sophomore rush’ and to suggest substitutes in the way of picked sides, brickbat contests at five hundred yards and the like. We, for our part, would enter strong protest against the discontinuance of the time-honored rush … We know from experience that class-room work, absorbing as it may be, does not develop an esprit de corps and fails utterly to give that peculiar flavor to college life which the old alumnus looks back to with a retrospective smacking of lips.

By 1900, more than lips were being smacked as rushing returned with a vengeance: “The night of the 5th October … was a night of horrid orgy,” reported the November 1900 Inlander student literary magazine. “The charging of multitudes of roughly clad youths … the stolen hat, glaring bon fire, the perfunctory arrests of the usual five, the mob clamoring for their release, the sudden peace in the dawning: all go to make up one’s impression of the Freshman-Sophomore rush.

Around the turn of the century, rushing had become a more formalized ritual, heralded by mocking posters sophomores pasted around town as in this 1903 example:

OH! JOY! FRESHMAN BLOOD!

You have encroached upon our sacred rights.

You have smoked on the Campus. You have been seen in our refreshment parlors.

You have enjoyed yourselves at the theater from the first five rows.

You have made goo goo eyes at the co-eds.

You have trespassed on our game preserves at Ypsi [the predominately female student body then at EMU].

For this you deserve DEATH. May your lot be fire and brimstone, hades without end.

The poster also invited all and sundry to a “Freshman Barbecue” featuring such dishes as “Fried ’07 Suckers,” “Prime Ribs of Fresh Beef,” and “Freshman Brains (?) in Season.”

Another new development in the tradition was a flagpole-climbing contest to capture the rival class’s flag. The January 1907 Michigan Alumnus included an article describing the custom:

When college opens in the fall and ye all-wise Freshman is given unceremonious introduction to the various niceties of university life, he learns from eager informants of that ordeal, known as the ‘banner-scrap’ … on a Friday evening several weeks after college has started, these members of the youngest class are formed about a flag-pole, located on the east side of the Campus. This flag-pole bears their first symbol of class unification and they are there to defend it with all the energy and determination that they possess. At a given signal, the Sophomores rush this band of Freshmen and the struggle lasts until the flag is captured by the older class, or until the Freshmen have defended it for thirty minutes.

After this evening rush was deemed too violent, the UM Senate and Student Council in 1909 altered the event to an afternoon scrap on Ferry Field called “Black Friday.” Posters, hazing, and the word “rush” were forbidden. Black Friday featured three 28-foot-tall poles, greased to nine feet high and crowned with the class and school banners.

The 1910 Michiganensian printed a vivid description of the event.

At two-thirty o’clock, [football captain] Dave Allerdice, the referee, gave the signal for hostilities to begin, and with wild yells the rival classes rushed to the poles, swarming about them in a frenzied attempt to gain the banners floating high above the ground.

Each class stationed a band of its best men to defend its own banner and with the remainder tried to capture the other two banners … [O]ne of the freshmen, climbing upon the heads and shoulders of the dense mass which surged about the middle pole [with a block M flag], managed to get beyond the reach of the sophomores and pulled himself up past the slippery part of the pole and then climbed the remainder of the distance to the flag without much effort. There was a shout of triumph from the first year men upon the achievement of this victory.

The freshmen then attacked the sophomore pole, said the article, and won that too. The article continued:

As in former years the winning of the rush was merely a preliminary victory. The real rush began when the freshmen, proud of their achievement, scattered over the field yelling and singing. The sophomores … organized themselves into squads and made every lone freshman they caught their victim. Not many escaped.

The trees surrounding Ferry field were well filled and an empty box car upon the siding of the Ann Arbor Railroad made a temporary prison.

Today the old tradition of the freshman-sophomore rush has faded away. Almost all evidence of the custom is gone – but not entirely.

The onetime sophomores plastering their rude and ribald posters around town little dreamt that one day, a few of those ephemeral scraps would end up in the Bentley Historical Library, as carefully curated fragments of a colorful chapter of Michigan history.

*Named for Robert Peel, who in 1829 created London’s first police force.

Mystery Artifact

Last week’s Mystery Artifact is answered in this column – though it’s a little unclear as to whether the student in question is grasping one of the greased poles or perhaps the “freshman tree.”

What do you think?

This week’s artifact also deals with wood. It’s an eight-and-a-half-inch long wooden device with a hand-carved wooden screw on top securing the movable square block.

The top edge of this object is ruled in inches.

What might it be? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is a local history columnist and collector of non-functioning Depression-era gas station cash registers. Her second book, “Hidden Ypsilanti,” is due out this fall. Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our publication of columnists like Laura Bien. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

I think it’s a depth gage, but I’m guessing it’s for some particular purpose and you want us to tell you what that purpose is. It would be too short for measuring how high up the greased pole that freshman made it…

Jim: It’s really a beautiful object…whatever it is. Imagine the skill and patience it took to carve that wooden screw…accurately no less.

I know exactly what that is, in fact they still make them, just like that. I would point out that the long part should be pulled out and rotated 90° left because there is a pin that goes in that hole on the right side, and it aids in it’s use if the ruler is on the side, not the top.

Its a woodworker’s scribe tool. Used to translate contours from one place to another.

Sorry Laura, I could not think of a marshmallow joke. Must be rusty.

Oh and as cosmonıcan says, “…they still make them, just like that.” Except that they come with metal screws now. So the skill and patience to carve a wood screw is no longer needed.

Cosmonican: Now here’s the strange part. I noticed that too, husband (engineering background) also commented on that aspect, and we very gently tried the rotation you mentioned (this is an artifact I have at home). For whatever reason, it does not fit that way. The bar and its hole (and the sliding piece with screw) are not square but shaped ever so slightly like a barrel, with very slightly curved sides. The bar does move very smoothly in its current position, with inscribed inch markings on the top and the little hole (unaccountably!) parallel to the surface it’s resting on. Which certainly adds to my bafflement.

ABC: Well, you can make marshmallows at home in a pan. And if I were to go through all that trouble I’d definitely want a tool to mark cutting lines to ensure optimum-precision marshmallows.

Problem solved, rotate the object, not the bar; who says the screw has to be on top? As far as carving screws goes, I can recall making those in 7th grade shop class (do they still have that?) and you can find wooden screws on things like nutcrackers, gift shop junk, et cetera. Wood workers have been making screws since before the pyramids, so they are very clever, but not rocket science either.

Seems like once you have one screw you can make as many more as you like (using the first one to turn a dowel as you cut into it with a bit). Or get one of these.