Ann Arbor Housing Commission to Expand?

The Ann Arbor housing commission board’s last meeting of 2011 was the first one attended by Jennifer L. Hall in her new role as executive director of the commission. Hall – who previously served as housing manager for the Washtenaw County/city of Ann Arbor office of community development – was selected by the board in October to replace Marge Novak, who had resigned in July.

Jennifer L. Hall, the new Ann Arbor housing commission executive director, talks with commission board member Andy LaBarre before the board's Dec. 21, 2011 meeting. (Photos by the writer.)

Most of the Dec. 21 meeting focused on a presentation by Hall. She gave an overview of local affordable housing demand, and looked at how the housing commission’s operations might address some of those needs. In part, her talk set the stage for possible land acquisition. Later in the meeting, the commission entered into closed session to discuss two potential properties it might buy to add to the city’s public housing stock.

On one of the properties Hall suggested constructing a rental project consisting of 22-37 detached single-family units and duplexes, ranging between 1-5 bedrooms. For the other property, she proposed building a 15-unit complex of detached 2-4 bedroom condos and duplexes, which would eventually be sold to low-income homeowners for $140,000 each. Funding for these projects would come from a variety of sources, including state and federal grants and loans.

The locations of the properties weren’t disclosed in open session. But Hall said she was looking for direction from the board on pursuing the two projects. If the projects move forward, more details would be discussed in the public portion of upcoming meetings.

Hall also floated the idea of changing the format of board meetings and of the information that commissioners receive in their meeting packets. She proposed cutting back on staff reports, presenting them quarterly instead of monthly. That way, more of the board’s meeting time would be freed to focus on strategic planning issues, she said.

Hall also suggested changing the way that meeting minutes are written up. Instead of including a detailed description of the board’s discussions, she said, the minutes could provide a summary of the discussion and a note about the outcome, if a vote is taken. Some commissioners expressed concerns about truncating the minutes dramatically. Board president Marta Manildi said the AAHC board would like a richer level of detail than what’s provided in Ann Arbor city council minutes, which she described as too terse.

During the time available for public commentary, two residents of Miller Manor – an AAHC apartment complex on Miller Avenue – raised concerns about security issues in the building. Manildi told them that their comments would be forwarded to a working group of staff that’s addressing security problems at all AAHC properties.

Affordable Housing in Metro Ann Arbor

Jennifer L. Hall began by telling commissioners that the topic of expanding the housing stock isn’t one she’d ideally choose for her first presentation as AAHC executive director. She noted that staff is doing a lot of work regarding maintenance, security and other operational issues.

But Hall told the board that two opportunities exist for possible land acquisition that could help add to Ann Arbor’s affordable housing stock. And she said it’s important to strike when those real estate opportunities arise. Her presentation was intended to set the stage for a strategic discussion, leading up to a closed session in which she’d provide more details about the two properties in play, including their location. The board could then give direction on the start of due diligence toward a potential acquisition. Depending on that direction, commissioners could eventually vote in open session at a later meeting on the real estate acquisition.

Affordable Housing: Context of Needs and Funding

It’s important to see how AAHC fits into the broader context of affordable housing in Washtenaw County, Hall said.

In 2007, the county did a comprehensive affordable housing needs assessment, looking at the gaps between the type of affordable housing that’s needed, and the type of housing that’s available. [The entire report is available to download from the Washtenaw County website.]

The assessment analyzed household characteristics, such as whether residents were disabled, had large families, or were low income. Different types of households have different needs – handicapped accessibility, for example, Hall said. Analysis of the county’s housing supply included the age and types of structures, as well as housing costs.

Other factors in the needs assessment touched on quality-of-life issues, such as proximity to employment sources, quality of schools, and access to services like groceries and medical offices. Hall also noted that the assessment looked at changes in affordability, measured in terms of housing values or rental costs, and the local levels of poverty and unemployment. Hall noted that the assessment was done in 2007, “before the economy went crazy,” so in some ways things have changed considerably since then.

Hall pointed out that Ann Arbor has benefited from its student population, in terms of federal funding, because students typically report poverty-level incomes. And because federal funding to communities from the U.S. Dept. of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) is based on formulas that are tied to poverty levels, Ann Arbor receives more funding than it otherwise would, Hall explained. HUD is looking to change that formula, she added, but the formula hasn’t been changed yet.

Affordable housing is defined relative to income levels – what is affordable to a higher income family is not necessarily affordable for a lower income family. For federal funding purposes, affordable housing means that a household is paying 30% or less of its gross income for housing, including utilities, taxes and insurance. Several HUD programs provide affordable housing assistance for low-income families – AAHC is one of the local entities that receives funding from these HUD programs.

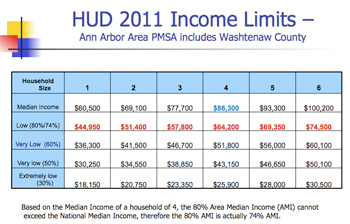

HUD 2011 income chart for Ann Arbor metro area, which includes all of Washtenaw County. (Links to larger image)

Hall reported the median income for various household sizes in the Ann Arbor metro area, which includes all of Washtenaw County. For a family of four, the median income is $86,300.

All of the other income definitions used by HUD are based on a formula, she explained. A family of four is considered low income if the household earns no more than 80% of the area median income. But that 80% figure can’t exceed the national median income, she said. So for the Ann Arbor market, with generally higher income levels, low income is set at $64,200 – instead of the $69,040 that corresponds to 80% of median income.

Assuming no more than 30% of income is spent on housing, Hall described maximum monthly housing costs for different income levels. For a family of four earning the area’s median income, monthly housing costs should be $2,158 or less. For a low-income family of four earning $64,200, monthly housing costs should be $1,605 or less.

Ann Arbor’s owner-occupied housing market is getting more expensive compared to other areas nationally. According to data from the National Housing Conference, in 2011 metro Ann Arbor (Washtenaw County) ranked as the 87th most expensive housing market among the nation’s 209 metro areas, Hall reported. The median home price for the Ann Arbor metro area was $162,000. Just two years earlier, the median home price was $136,000, and metro Ann Arbor ranked 132 among the 209 metro areas, she said.

For the rental market, metro Ann Arbor also ranked 87th among the 209 markets in 2011, with an average monthly rent of $882 for a two-bedroom apartment. But that is a drop in the rankings from 2009, when the area ranked 51st with an average monthly rent of $940.

Commissioner Leigh Greden commented that if you looked at the Ann Arbor market alone – not including the rest of Washtenaw County, where house values and rents are generally lower – the cost of housing would be even higher than the amounts reflected in the metro area data.

Hall observed that as people search for affordable housing and move further away from where they’d prefer to live, they often increase the amount they pay for transportation to get to work or to necessary services, like grocery stores. That increased cost often isn’t factored in to their housing decisions, she noted, and the more distant location can end up being more expensive overall.

Turning to rental housing, Hall noted that in an ideal world, every household would live in a unit it could afford – there would be units available for all income levels. But “unfortunately, that’s not the way the market works,” she said. There’s a mismatch of availability and income, with some families paying more than 30% of their income for rent, and others paying far less than 30%.

Affordable Housing: Fair and Equitable

Introducing the issue of fair and equitable housing, Hall noted that compared to the rest of Washtenaw County, Ann Arbor is a community with more jobs, good schools, public transportation – all of the things you’d want for everyone. And the Ann Arbor city council has been more supportive of low-income rental housing than governing bodies of other communities, she said. But while there are pockets of poverty in Ann Arbor – on the southeast side, for example, or the Arrowwood Hill Cooperative in the north – much of the county’s poverty is concentrated in the Ypsilanti and Ypsilanti Township area, Hall said.

HUD has traditionally provided more funding for low-income housing in low-income areas. But Hall noted that a fair and equitable approach would be to make affordable housing available throughout the community, not just in low-income areas. HUD seems to be moving in that direction, she added. For example, the $3 million “sustainable community” grant that was recently awarded by HUD explicitly requires that low-income housing not be built in low-income areas.

Commissioner Gloria Black noted that the Ann Arbor city council might be supportive of this integrated approach, but what about Ann Arbor residents? Hall replied that she has never seen a new construction project for affordable housing that was supported by 100% of the neighbors. “That doesn’t mean you can’t get it done,” she added. It means you need to meet with neighbors and explain the project, she said, get their input and hopefully address their concerns.

As an example, Hall cited the Near North project, a residential affordable housing complex planned for North Main Street and spearheaded by the nonprofit Avalon Housing. It was originally planned to be a four-story, 60-unit structure, but was redesigned to three stories and 39 units in order to address concerns from the neighbors, she said, even though the smaller scale made financing the project more difficult. [Specific objections of neighbors related to the scale and massing of the building.]

Marta Manildi observed that in general, getting the acceptance of neighbors might be related to the quality of the project.

Affordable Housing: AAHC’s Role

Hall spoke about the role of the Ann Arbor housing commission in a continuum of affordable housing throughout Washtenaw County. On one end are shelters for people who are homeless, including the Delonis Center, SafeHouse Center (for victims of domestic violence), Interfaith Hospitality Network’s Alpha House (for families), and SOS Community Services, which runs a housing access hotline. At the opposite end is market rate housing that is affordable. Within those extremes, Hall outlined a range of other housing assistance and types:

- Transitional housing (Dawn Farm, Michigan Ability Partners, Home of New Vision)

- Group homes (Synod House, Washtenaw Community Health Organization)

- Senior assisted-living (Area Agency on Aging 1-B, private sector)

- Nonprofit supporting housing (Avalon Housing, Michigan Ability Partners, Community Housing Alternatives)

- Senior housing (Lurie Terrace, Cranbrook)

- Public housing (Ann Arbor Housing Commission, Ypsilanti Housing Commission)

- Tenant vouchers (Ann Arbor Housing Commission, Ypsilanti Housing Commission, Michigan State Housing Development Authority)

- Private developments (Windsong)

- Cooperatives (Arrowwood, Pine Lake, Forest Hills, University Townhomes)

- Houses for homeownership (Habitat for Humanity and other nonprofits)

- Units within private developments (First & Washington, Stone School)

AAHC manages two main programs: (1) the Section 8 voucher program for Washtenaw, Monroe, and western Wayne counties; and (2) public housing units in Ann Arbor. For Section 8, over 1,400 vouchers are in use by tenants to subsidize rent in privately-owned properties. In addition, 37 vouchers are tied to specific projects: 20 for Avalon Housing’s Pear Street apartment complex; five reserved for a to-be-determined Avalon property; and 12 for assisted living in units managed by Area Agency on Aging 1-B. There’s also one homeowner voucher, Hall said, for an AAHC lease-to-own property.

The public housing units managed by AAHC are located throughout the city of Ann Arbor. AAHC units include Miller Manor, Baker Commons, North Maple Estates, Hikone and Hillside Manor, among several other properties. The inventory of 360 total units includes 30 single-bedroom units, 163 single-bedroom units for the elderly or disabled, 166 family units with 1-5 bedrooms, and one three-bedroom lease-to-own family unit.

Hall noted that the AAHC’s last development – two duplexes on North Maple – was completed in 1998. Most of the AAHC housing stock was built in the 1960s and 1970s, she said. It’s aging, and requires a lot of investment to maintain.

AAHC’s mission is to provide low-income housing, Hall noted. Very few sites in the city can be developed for that, so when opportunities arise, it’s important to look at possible acquisitions as an option to increase the number of affordable housing units in the city, she said.

Greden asked whether opportunities exist to work with the county treasurer on acquiring foreclosed properties. Hall told Greden that working with the county treasurer was an option, but she noted that most tax-foreclosed properties are located outside of Ann Arbor.

Regarding the possible acquisition of additional AAHC properties, Manildi asked whether the need for expansion is a function of the need for additional affordable housing units, or a function of the need to replace existing units that are in poor condition.

Hall replied to Manildi by saying that both reasons are driving the discussion. The previous AAHC executive director, Marge Novak, had started the process of evaluating all the public housing units to see if the units need rehabbing or should be torn down and rebuilt. In two cases, existing units are located in floodplains, Hall said, so rebuilding isn’t an option. Baker Commons, located at Packard and Main, is an example of a complex that needs reinvestment, she said.

But overall, “there’s a huge shortage of affordable housing,” Hall said.

Black observed that AAHC has only one lease-to-own property. It seems there’s a focus on rentals and a movement away from homeownership, she said. She wondered whether AAHC should try to convert apartments to condominiums that tenants could purchase, and move them off of public housing assistance.

Hall responded to Black by noting that AAHC originally had 50 lease-to-own properties, and all but one of those tenants had been able to purchase their homes. Manildi noted that it’s not clear whether it’s better for a tenant to rent or own. She allowed that stability is important – in terms of residents remaining in the same location and maintaining the property. But it’s not clear that there’s an economic advantage to ownership, Manildi said.

Hall agreed, pointing out that in addition to housing costs like mortgage payments and utilities, homeowners also incur costs like roof replacement and other maintenance. The foreclosure crisis was caused by people being overextended, buying houses that they couldn’t afford, she said.

But isn’t homeownership the American Dream? Black asked. People might take better care of their homes if they owned the property. Just because people are poor doesn’t mean they don’t have a vision for homeownership, she said. The goal should be to eliminate the need for public housing completely, Black added. The government doesn’t want to be in that business, and low-income residents don’t want it, either. Andy LaBarre weighed in, saying “I’m not quite sure we’re there yet.”

Hall returned to the issue of demand, noting that when AAHC last opened its Section 8 waitlist in 2006, more than 3,000 people applied. That comment prompted someone in the audience to ask when the Section 8 waitlist would be opened next. When it opens, he added, “there’s going to be a stampede.”

Section 8 waitlists are opened for new applicants every two to four years. Wenisha Brand, AAHC Section 8 housing manager, reported that she hoped to open the waitlist soon, but there is no firm date yet. When those decisions are made, the information would be posted on AAHC’s website, as well as in other public locations.

Affordable Housing: Potential Acquisitions – Homeownership

While still in open session, Hall provided some details about two possible AAHC projects – one for eventual transition to homeowners, and another for rental. She said the board could continue this discussion at its January meeting, and that local attorney Rochelle Lento has offered to provide pro bono assistance for the real estate transactions.

The first possible project would involve constructing a 15-unit complex of detached 2-4 bedroom condos and duplexes. It would be a “green” construction project, which would make it eligible for certain grants. The project could be pursued in partnership with the city’s parks department, which is interested in a portion of the property for the parks system, Hall said. Habitat for Humanity is another potential partner.

Development costs for this first project would total an estimated $3.74 million, or $249,000 per unit. That total includes acquisition costs ($160,000), construction ($2.1 million), site improvements ($400,000), developer/staff fee ($450,000), professional fees ($300,000), homeowner education workshops ($30,000) and soft costs, such as financing ($300,000).

Several financing sources are available, Hall said, but the main financing would be a construction loan estimated at $1.855 million. Other sources include a Federal Home Loan Bank grant ($225,000), the city of Ann Arbor’s housing trust fund ($50,000), brownfield tax-increment financing ($560,000), green construction and private grants ($300,000), a portion of the $3 million HUD Community Challenge grant ($340,000), education grants and fees ($10,000), and HUD funding through the Community Development Block Grant and HOME programs ($400,000).

Down payment assistance would be available to qualifying low-income families, Hall noted. The units would be sold at an estimated $140,000 each – affordable for residents in the 50%-80% of the area’s median income. Deducting $125,333 in anticipated grant subsidies from the $249,000 development costs would result in a $123,667 loan repayment per unit, Hall explained. If the homes are sold at $140,000, that leaves a $17,000 profit margin for AAHC per unit.

Affordable Housing: Potential Acquisitions – Rental

Turning to the rental project, Hall told commissioners it would involve between 22-37 detached single-family units and duplexes, ranging between 1-5 bedrooms. As with the other project, the property acquisition might occur in partnership with the city’s parks system, and would aim to be a green construction project. Avalon Housing might be another potential partner, Hall said.

Fewer details were available on the specific financing for this rental project. Possible funding sources include low-income housing tax credits, HOME funding, a Federal Home Loan Bank grant, a 221(d)3 mortgage insurance and loan, Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA) bond financing, and a HUD Section 202 or 811 grant.

Hall wrapped up her presentation, and the board moved into closed session to discuss the possible land acquisitions.

Closed Session: Land Acquisition

At the beginning of the Dec. 21 meeting, the board had voted to change its agenda so that the planned closed session could be moved up on the agenda. Commissioner Leigh Greden had to leave the meeting early, and the timing of the closed session was changed to accommodate him.

The closed session lasted about 30 minutes, and Greden left the meeting when commissioners returned to open session. Board president Marta Manildi reported that the group had discussed only one of the two properties, and had deferred discussion on the second property until a future meeting.

AAHC Board’s Role, Meeting Format

Toward the end of the Dec. 21 meeting, AAHC executive director Jennifer L. Hall brought up a discussion item about the board’s monthly meeting format and information packet. She said she’d like the board meetings to be focused on strategic planning and big-picture issues. Currently, much of the meeting time is taken up with staff reports on AAHC’s day-to-day operations.

Saying she didn’t think that was the best use of the board’s time, Hall proposed cutting back on staff reports, suggesting they be presented quarterly instead of monthly. The board’s main responsibilities are fiduciary and strategic, Hall said, and she wanted to spend more time on those issues.

Ann Arbor housing commission board member Gloria Black, left, talks with Wenisha Brand, AAHC Section 8 housing manager.

Commissioner Gloria Black said she had no objection to Hall’s suggestion, but she wanted to ensure that the board was regularly updated on concerns that AAHC residents raise during public commentary. The board should be notified of how AAHC staff have followed up on those issues, she said.

Commissioner Andy LaBarre supported the change in format, saying it made sense and would make the meeting more efficient, with time for useful dialogue on strategic issues.

Commissioner Ron Woods asked for more details about the proposed format change. Hall explained to Woods that the current board packet for each meeting includes a level of detail that she doesn’t feel is necessary – for example, a report on vacancy rates for each AAHC property. Perhaps quarterly reports on finances and operations, with a summary overview, would be more appropriate, she said. Woods noted that he’s found the current reports useful, but he’d support anything that would make the organization more efficient.

Board president Marta Manildi indicated that her initial reaction was positive. The board has worked hard on “nitty gritty” areas over the last two years, she said, and it’s time to focus on long-term and strategic issues. At the same time, she added, the AAHC’s culture is not to set itself apart from the residents it serves or from the staff. It will take a certain judgement about the level of operational detail that the board needs, she concluded. They should try a new format, and the board can give feedback about whether it’s working, she said.

Hall also suggested changing the way that meeting minutes are written up. Instead of including a detailed description of the board’s discussions, she said, the minutes could provide a summary of the discussion and a note about the outcome, if a vote is taken.

Black expressed concerns about paraphrasing the board’s deliberations in the minutes. Hall described a spectrum of options – from a recording of everything that was said during the meeting, to a summary that provides a gist of the conversation. Manildi quipped that too much detail would result in terminal boredom, but that the city council minutes are too terse. The AAHC board would like a richer level of detail than what’s provided in city council minutes, she said.

Hall suggested providing more detail in the minutes when the board discusses a critical policy question. For other issues, a summary could be given instead of a blow-by-blow report.

LaBarre requested that the board’s electronic information packets be reduced to 3MB or less, to make them easier to access on a mobile device. Deputy director Nick Coquillard said AAHC will likely start posting the packets online, just like the meeting minutes are already. Manildi commented that making the packets accessible online would be a good move in general, to make the information more easily available to the public.

AAHC has installed a computer kiosk at its Miller Manor offices, Coquillard noted. It allows residents to access the commission’s website, the city of Ann Arbor’s website and other online resources. The goal is to add similar access at AAHC’s four community centers and at Baker Commons, he said. Coquillard explained that the kiosk is simply a computer monitor that hooks up to the city’s IT infrastructure, so the cost – and risk of theft – is minimal.

Public Commentary

Two people spoke during public commentary at the beginning of the Dec. 21 meeting, both addressing security issues.

David Guidas noted that he had spoken to the board about three months ago regarding security concerns at Miller Manor. One of his concerns is that the apartment doors can be easily kicked in. He held up an example of a metal wrap-around security plate that he’d purchased and was planning to install on the door to his apartment. He said he’d let commissioners know how it worked out.

Tracy Odgers told commissioners that she had lived at Miller Manor since 2003, and reported that there are all kinds of security problems. Security cameras in the building are really outdated, and theft is an issue – a VCR had been stolen in the middle of the day, she said. Odgers suggested updating the security cameras, and installing them in more locations, including hallways and elevators.

Public Commentary: Commissioner Response

Marta Manildi told the speakers that there is a working group of AAHC staff focused on security issues, not just at Miller Manor but throughout the city’s public housing properties. She said the comments would be forwarded to that group, and she thanked them for their input.

Gloria Black, the board’s representative for residents of AAHC properties, told the speakers that it takes a long time to address these concerns, but she wanted them to know that their comments had not fallen on deaf ears.

Present: Gloria Black, Leigh Greden, Andy LaBarre, Marta Manildi, Ronald Woods. Also: AAHC executive director Jennifer L. Hall; AAHC deputy director Nick Coquillard; Weneshia Brand, Section 8 housing manager; Kevin McDonald of the Ann Arbor city attorney’s office; Sharie Sell of the city’s human resources department; Margie Teall, Ann Arbor city council liaison.

Next meeting: Wednesday, Jan. 18, 2012 at 6 p.m. at Baker Commons, 106 Packard in Ann Arbor. [confirm date]

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public bodies like the Ann Arbor housing commission. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

It appears that Jennifer Hall, whose history is with both the Ann Arbor Community Development department, and the Washtenaw County-Ann Arbor Community development department (now known as the Urban County), is attempting to recreate a Community Development department within the Housing Commission. The Housing Commission has always been the overseer for public housing under the old Federal program that was discontinued decades ago. This would be a major expansion of its role – becoming a developer of affordable housing, and not public housing but even housing to sell?

Isn’t this a duplication of the Urban County, without the access to the CDBG funds that have been used in the past to pay for affordable housing initiatives in the city? We have turned that access over to the Urban County. (I reviewed this recently, and mentioned the sustainable communities grant, in a blog post [link])

The sustainable communities grant referenced in the article was under a program that has been terminated (after this last round of awards). It was partly funded through transportation funding and was “zeroed out” by Congress in recently passed transportation legislation. Thus, it will not be available for future funding.

The grant was a tour de force for Hall in her previous county position, and she successfully solicited letters of cooperation from virtually every local agency and government. Many of these offered “leverage” matches, money already allocated to supportive projects. As nearly the only cash match to the grant proposal, the City of Ann Arbor has promised $550,000, part of which is from the Parks Acquisition (Greenbelt) millage and part from the Park Maintenance millage. Apparently those amounts are to be used in acquiring the property discussed in this article.