In the Archives: “Freedmen’s Progress”

Editor’s note: Laura Bien’s In the Archives column for The Chronicle appears monthly. Look for it around the end of every month or sometimes towards the beginning.

A recent Ward 1 Ann Arbor city council candidate forum included some discussion of the African American Cultural and Historical Museum of Washtenaw County, to be located on Pontiac Trail. In this month’s column, Bien takes a look at one piece of African American history with an Ann Arbor connection – the 50th anniversary of the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

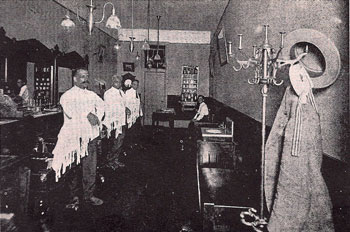

Ann Arbor barber Henry Wade Robbins is one of many Washtenaw County residents singled out for commendation in a largely forgotten but historically invaluable book assembled in just three months in 1915. “Mr. Robbins has completely negated the popular fallacy that in order to be successful in the barber business the boss was required to draw the color line in his patronage,” says the work’s biographical entry for Robbins.

“This Mr. Robbins has never done. He treated all gentlemen alike and catered to high-class trade, both white and colored, and he has numbered and still numbers among his patrons many of the best-known white people in Michigan …” Robbins owned his own shop and its upstairs apartments at 117 Ann St. where he, his wife Martha, and their son and daughter lived.

The book’s data on employment, home ownership, and achievements by black Michiganders was collected and compiled by a panel of Michigan African Americans selected by Michigan governor Woodbridge Ferris. Their work was compiled into the “Michigan Manual of Freedman’s Progress” (MMFP), which offers a cross-section of successful black Michiganders in the early 20th century.

The impetus for creating the MMFP came from Gov. Ferris. The “National Half-Century Anniversary of Negro Freedom and the Lincoln Jubilee” was scheduled to take place in Chicago in the summer of 1915, celebrating 50 years of freedom for black Americans following the 1865 ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which reads:

1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Congress passed the amendment on January 31, 1865. Lincoln’s home state of Illinois became the first state to ratify it on February 1, followed by Rhode Island and Michigan on February 2, 1865. Five decades later, the Lincoln Jubilee commemorated the amendment’s passage.

Michigan was represented in Chicago at the Jubilee. Some months before that event, Gov. Ferris asked black staff assistant Charles A. Warren to contact 57 black leaders from around the state and request their aid in organizing a Michigan exhibit for the Jubilee. The group met with Ferris to discuss logistics and legislative support. Public Act 47, approved in mid-April of 1915, guaranteed $5,000 for the project [about $110,000 in today’s dollars] and stipulated that the people of the state of Michigan would “provide for the preparation, transportation, and care of a Michigan exhibit at the [Lincoln Jubilee].” A Freedmen’s Progress Committee was appointed to govern the work.

The act also said that the exhibit would include “a manual showing the professional, political, religious, and educational achievements of [black] citizens of this state …”

Though there were only a few months in which to gather information, the eventual manual included meticulously tabulated lists of the over 1,200 black Michiganders who were homeowners and the more than 1,600 black Michigan soldiers who had volunteered to fight in the Civil War. The MMFP acknowledged that given its time constraints, the actual numbers could be higher.

The work also provided biographical sketches of successful black Michiganders. In addition to Henry Wade Robbins, other Ann Arborites include surgeon Simeon Carson, postal carrier Robert Carson, Reverend W. B. Pearson, and physician Catherine Crawford. The work omits William Blackburn, then one of only 10 black policemen in the state.

The 43 black Ann Arbor homeowners listed include porter Levi Bates at 808 4th Avenue. The widow Frances Bubbs worked as a cook for Phi Delta Theta fraternity and owned a home at 1009 Ann St. Teamster William Grayer and his family lived at 1131 Traver. William Henderson, a chef at Kappa Sigma fraternity, resided with his wife Amelia at 701 4th Avenue. Janitor Edward Lewis and his wife Magnolia lived at 1009 Catherine.

Ypsilanti professionals cited in the MMFP include professor Louis Slater Bowles, Reverend I. F. Williams, physician John H. Dickerson, lawyer John H. Fox, and stenographer Carrie Hayes. Among the 68 Ypsilanti homeowners are foreman Abraham Woods at 320 Harriet, house mover Solomom Bow at 420 Washington, Reverend James Derrick at 531 Jefferson Ave., and George Richerson, the “wealthiest farmer in Ypsi,” according to the MMFP.

In 1915, Washtenaw County held the distinction of having Michigan’s second-highest per capita rate of black home ownership relative to total county population, exceeded only by Cass County. One factor in both counties’ significant number of black residents was the historical presence of Quaker residents, many of whom actively participated in the Underground Railroad.

The MMFP also catalogued the 196 exhibits from around the state displayed at the Jubilee. These included such handwork as fine lace, embroidery, quilts, clothing, and painted china. Artwork included a variety of paintings, photographs, and examples of printing and bookbinding. Inventions, blueprints, and patent documents were also on display, as well as a variety of agricultural products. Photographs highlighted homes and businesses built and owned by black Michiganders.

Washtenaw County boasted nine contributors to the exhibition, most of whom were from Ypsilanti. Ypsi confectioner Frank Smith sent a variety of candies. Carrie Hayes and Elizabeth Mofford offered their handmade slippers. Anna Clark and William Henry James loaned their “fancy work.” Fred Warren contributed a handmade cane, and Mrs. Wealthy Sherman a handmade rug. The remaining two contributors came from Whittaker, a hamlet just south of Ypsi: Emanual Carter with poultry and a Mrs. Clark with artworks.

The items went on display at the Jubilee, which also featured speeches, musical performances that included a mammoth choir of hundreds of singers, and other states’ exhibits of black Americans’ inventions, artworks, and achievements in business, manufacturing, and agriculture. The Jubilee was held from August 22 to September 16. Over 10,000 people attended the its opening ceremonies and an estimated 100,000 persons had visited by the time it closed. Though the Jubilee was open to all, one visitor estimated the ratio of white attendees at only five percent.

One chapter of the MMFP illustrates the sociocultural context for the achievements documented in the book. The book’s preface offers an analysis of the portrayal of black Michiganders in the media. Written by Freedman’s Progress Commission secretary Francis Warren, the essay attributes a perceived early-1900s rise in hostility towards black residents to a skewed representation in newspapers.

In a great majority of instances when the term ‘Negro’ is used in news matter, it refers to the criminal Negro and not to that vast bulk of black people who are making good and pursuing the even tenure of their way. Ordinarily, on the other hand, when many of the newspapers mention anything commendable about a black man, his racial character is not mentioned … the press emphasizes the racial character of black criminals and suppresses the racial character of black persons performing good deeds …

Warren cited several examples culled from Michigan papers. He then presented a table summarizing an analysis of the use of the word ‘Negro’ in six months’ worth of articles collected from Detroit papers.

Of 232 articles, “nearly 200 of them referred to the Negro in a manner that was not commendable.” Only 36 of the articles were “commendatory of Negroes.”

“This constant bombardment of the moral character of black people has produced an apparent growth of hostility to the Freedman in recent years,” Warren wrote.

Against such a backdrop, the achievements listed in MMFP shine all the brighter. The Michigan Manual for Freedmen’s Progress preserves a record of ambition, perseverance, talent, and success, and ensures that the artists, inventors, businesspeople, physicians, lawyers, teachers are remembered – as well as one Ann Arbor barber who parlayed a seemingly humble skill into wealth and comfort.

Mystery Artifact

Only one person guessed the identity of last column’s baffling Mystery Artifact. It was a stumper, to be sure! This artifact was brought into the Archives by a visitor (and used as a Mystery Artifact here with his permission) and neither I nor anyone else there at the time could guess what it was.

When the owner found out, by consulting with the owner of Ypsi’s Automotive Museum, he called the Archives and we were fascinated to find out that this is one side wheel from an old push mower.

Chronicle reader Russ Miller guessed that this object was “a wheel from reel type push mower – with perhaps a gear cast into a drum on the back side. Seems like an awfully skinny thing to push across a lawn but there might have been a hard rubber tire cast on the rim. ” Great guess, Russ! And there is indeed a gear case into the body of the object on its nether side.

This time we have one of those artifacts that will be easy for some folks and completely unfamiliar to others. Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Hidden History of Ypsilanti” and “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Look for her article on Coldwater School, a short version of which first appeared here, in the July/August issue of Michigan History Magazine. ypsidixit@gmail.com

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our columnists like Laura Bien and other contributors. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

Marshmallow torture kit?

Looks like sewing machine feet, but I don’t know ’bout sewing, so it could be some sort of fiendish surgical kit too. Nice box though.

hey, William and Amelia Henderson lived in my house!

…and they always left the toilet seat up.

Laura, would these black homeowners you listed have had any white neighbors? I’m just wondering about the nature of those neighborhoods in the Old 4th Ward (and on Traver).

ABC: Hmm, interesting idea. If so this is a pretty detailed and diabolical kit, presenting at least 25 ways to inflict torture via marshmallow. Possibly a relic from the International Spy Museum?

Cosmonican: It IS a lovely box. This box is about 90 years old. Works perfectly. Fits exactly when closed. It’s a beautiful piece of craftsmanship.

John: Thank you for reading! I have news for you, sir: your home (if it was the same structure) was also the home of William Blackburn, the black AA policeman in the article:

1897 AA city directory: Blackburn, Wm. E (Clara) deputy sheriff, residence 701 4th Ave.

1917: Henderson, Ferdinand (wife Myrtle) porter Delta Chi fraternity, boards 701 4th Ave.; Henderson Wm. N. chef in restaurant, residence 701 4th Ave. (Ferdinand his son?)

1922: Davis Daniel S. (wife Iva M) contractor, 701 4th Ave, residence same (apparently he ran a business from the home).

Joan: It would take a lot of analysis in the old city directories to be able to give you a good answer. Which I would be happy to do, but just saying I can’t give you a solid answer at this time. Also, there are so many excellent historians in AA who would likely have much better info than me…Ypsi is really more of my beat. In the meantime, the AADL has a set of old directories if you wish to check out the history of Traver. :)

Re #5. Joan should remember voting (twice) on whether the Traver/Broadway neighborhoods would become historic districts. Research on the properties along Traver, Broadway, Jones and adjacent streets indicates that the North side of town was populated by diverse people, living side by side. There was no red-lining on the North side.

The North Central neighborhood — where John Hilton lives, was also mixed, with railroad laborers’ rooming houses and a variety of residents over the years. However, this part of town was impacted by redlining.

(For those unfamiliar with this term, “redlining” was coined in the late 1960s by John McKnight, a Northwestern University sociologist and community activist.[6] It describes the practice of marking a red line on a map to delineate the area where banks would not invest; later the term was applied to discrimination against a particular group of people (usually by race or sex) no matter the geography. During the heyday of redlining, the areas most frequently discriminated against were black inner city neighborhoods. ” (Wikipedia. See also this sample map: [link])

Thanks, Sabra. I do remember voting, but didn’t remember the details about the neighborhood and the redlining. Very interesting, indeed.

The mystery artifact is definitely a kit with all the attachments for an old sewing machine.

Irene, with help from daughter Becky

More specifics about the artifact. It is for a 1889 model Singer. The box folds in the center to enclose the attachments.

Irene Hieber

Irene: A very specific guess! With even the year! I”ll post the answer next column.

I’d be astounded if something about Elijah McCoy wasn’t included in the MMFP. He was certainly well known by then, as he is listed in Booker T. Washington’s 1909 “Story of the Negro.” A prolific inventor, he is best remembered for an oil-cup lubricator that revolutionized steam locomotion after WWI. He lived in Ypsilanti.