In the Archives: Michigan Merinos

Washtenaw County owes a long-forgotten debt to Napoleon Bonaparte.

In the chaos following Napoleon’s first invasion into Spain in the early 19th century, the Spanish crown lost control of a resource it had jealously guarded since its acquisition from the North African Berber people in the 11th century.

For centuries, Spanish royalty forbade this resource to leave the country, and Spain steadily accumulated wealth from the commodity it produced. One expenditure of this wealth funded a young Italian explorer on his 1492 journey to what he apparently expected would be India.

This possession was the royal flocks of merino sheep, and the commodity was arguably the finest, softest, most luxurious wool on the planet.

Some American statesmen in Europe in the early 19th century took advantage of the post-invasion upheaval to smuggle out these esteemed sheep.

One was the Lisbon-based American consul to Portugal, William Jarvis. Around the turn of the 19th century, he shipped a dozen merino sheep to America. They sold for $15,000 [$216,500 in today’s dollars].

When Madrid-based minister David Humphrey’s term ended, he asked if instead of the usual parting gift of 100 bars of silver he might take home a few merinos. His request was granted sub rosa. The minister to France, Robert Livingston, obtained a few. So did George Washington. More were smuggled in for Thomas Jefferson, who began a merino breeding program at Monticello. When Jefferson was elected president, his merinos accompanied him to Washington, pastured on the White House lawn.

The merino craze was on.

Some eight decades later, the descendants of sheep from the Jarvis and Humphrey flocks were raised on the Ypsilanti farm of J. Evarts Smith.

The war of 1812 enforced a blockade of cheap British textiles and helped to spur a “merino bubble” akin to the Netherlands’ tulip mania of the 1630s. When the merino bubble collapsed around 1815, some animals sold for $1, and wound up on the dinner table.

Despite the collapse of the merino craze, the animals were nevertheless a valuable producer of good wool. The first record of Spanish merinos in Michigan dates from 1828, according to an 1892 report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Stephen V. R. Trowbridge, of Oakland County, began with a flock of 18 sheep, and without purchasing any, and killing and selling 500, had in 1851 over 450. They were full-bodied Spanish merinos, and were found to thrive above all other sheep.”

When Trowbridge obtained his sheep in 1828, Michigan had a population of about 31,000 settlers. Many pioneers hewed their farms from woodlands. These stump-littered plots were ideal pasturage, it turned out, for the merino. Though its wool was delicate and fine, the animal itself was well-insulated for Michigan winters, and did not require special food during the growing season, as it could feed itself solely on foraged plants.

Around 1836, the merino was introduced to Washtenaw County by Saline’s Thomas Wood, according to the same federal agricultural report. Wood’s first ram, imported from New York, led to a sheep empire of sorts and helped make the county one of the state’s leading merino hotspots.

Four years later, one Captain Lowry of Lodi Plains in Lodi Township imported some merino ewes. The breed was catching on and would eventually become the dominant breed of sheep in the lower half of the lower peninsula.

In those early days – with settlers scattered about the state combined with a scarce infrastructure of woolen mills to process their “clip” – most farmers raising sheep sent their clips to Detroit. In 1841, Detroit exported 20,000 pounds of wool. Just three years later, the harvest had increased by more than elevenfold to 230,000 pounds. By 1847 it was a million pounds

In 1840 and 1850, Michigan was fourth in the nation in sheep population. In 1860 it was top-ranked, and maintained that Number One ranking for the next 50 years. Within that half-century, the leading decade was the 1880s – the golden era of Michigan sheep husbandry.

In 1880, the Michigan Merino Sheep Breeders’ Association formed. The group’s reports listed purebred registered flocks and pedigrees of individual sheep. Ewes were denoted by numbers only, but rams bore names such as “Gold Drop,” “Premier,” “Sweepstakes,” or “Greasy Bill.”

To take a snapshot of that year, it is worth perusing the 1880 census agricultural report for Ann Arbor Township. Almost all Washtenaw County farms of the era were mixed-use farms. The monocultural farms of corn or soybeans seen in modern-day rural lower-peninsular Michigan did not yet exist. The farmers of 19th-century Michigan hedged their bets by farming a wide variety of livestock and crops.

Of the 279 farms listed for Ann Arbor Township in 1880, 93 included sheep, or 30%. Thirty farms, or 9.3%, had herds of over 100 sheep. The leading sheep farmers were Isaac Dunn with 415 sheep on his 50-acre farm, Richard [Newland] with 415 on 200 acres, and Oscar Ide with 380 on his 200 acres.

Dunn was an experienced sheep farmer. In 1863, he produced over a ton of wool, garnering a mention in the Ann Arbor Argus that was reprinted in the July 1863 issue of The Michigan Farmer magazine. He “delivered his clip of wool on contract in this city last week. He brought it (2,100 pounds) at one wagon load. It was purchased by P. Balch, at 60 cents per pound. Nearly $1,300 [24,000 in today’s dollars].”

By 1880, Dunn’s wool production was up to 3,700 pounds, if the census-taker’s scribbled handwriting can be trusted [One does wish the federal government gave handwriting tests to census-takers!] That year, Dunn also earned revenue from the 500 pounds of butter produced from his 8 cows, as well as the 50 dozen eggs from 20 chickens, his 6 acres of “Indian corn,” 4 acres of oats, 8 acres of wheat, a quarter-acre of potatoes, 10 acres of apple trees, 10 pounds of honey, and 30 cords of cut firewood. Dunn’s sheep roamed his farm acreage located just off the present-day Nixon Road between Pontiac Trail and Plymouth Road.

Annual competitive sheep-shearing festivals became popular across Michigan, usually held in April. Many occurred in Washtenaw County, such as the April 22, 1882 shearing festival in Manchester, the April 15 and 16, 1886 shearing at Ann Arbor, and shearings at Saline as well as throughout the lower half of the lower peninsula.

In 1885, 207 merino flocks were registered with the Michigan Merino Sheep Breeders’ Association. By 1889, the number of flocks grew to 297, and by 1897, 350. That year, Washtenaw County led the state in number of sheep and pounds of wool, followed by Eaton, Jackson, and Calhoun counties. The top ten lower peninsular counties produced half of Michigan’s wool. Saline and to a lesser extent Ypsilanti led the county in wool production.

Washtenaw County sheep were exhibited at the celebrated 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, as noted in the October 13, 1893 Ann Arbor Argus. “In the Michigan awards at the World’s Fair,” the paper reported, “… Washtenaw county stands well up in the list … W. E. Boyden, of Webster, gets the first award on merino ewes, three years old or over, while A[rthur] A. Wood, of Saline, gets the third award … Washtenaw is still a sheep center.”

The merino sheep’s dominance in Michigan sheep husbandry began to fade after the turn of the 20th century. In 1899, the majority of Michigan counties show a decrease in the production of merino wool, and the 1909 Michigan Merino Sheep Breeders’ Association Register lists only 127 flocks.

Over time the “fancy” merino faded from fashion. To this day, however, Washtenaw County leads the state in heads of sheep, according to the most recent USDA Census of Agriculture figures.

The onetime possession of Spanish royalty, transported over an ocean to rough-hewn frontier farms, helped shape the future of Washtenaw County and the state as a whole.

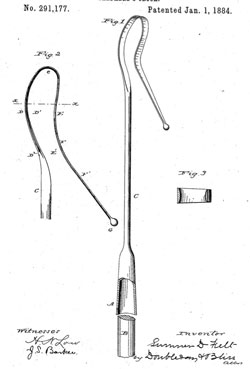

Mystery Artifact

Last column, Jim Rees correctly guessed the mystery object.

Rees described it like this: “The object in the diagram is obviously a telephone. A very old one, with a ‘non-metallic’ or ‘earth return’ connection. These were very susceptible to lightning, and Fritz is right, the toothy thing is what we would today call a ‘surge suppressor’.”

Also, Fritz Passow correctly guessed that this is “a diagram for how to keep lightning from blowing up your phone, or at least not burning down your house when it does. The pair of close-spaced toothy things on the left is the gap the lightening is supposed to jump on the way to Earth.”

Disclaimer: Fritz is my husband but did not receive any hints about this artifact.

This column, we have an obscure patent related to SE Michigan. What might it be? Take your best guess!

Contact Laura at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to keep readers informed about Washtenaw County’s dominance in sheep farming. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

Hmm. I wonder if the usual-suspect guessers seem are completely stumped. Laura doesn’t provide us here at The Chronicle with the description of the mystery objects in advance, I’ll go ahead and take a shot.

I think this is related in some way to maple sap tapping. The gaget at the bottom taps into the tree and the little hood type piece fits over that and leads the sap into the bucket down the flexible tube part. It was a clever ploy to orient the drawing upside down, but that didn’t fool me!

Nope Dave, it’s too easy. Hint: crop out the patent number next time.

I’m not going to cheat by looking up the patent number.

I don’t think it’s a tube. It’s too flattened at the top, and there is no visible opening in the upper end.

It reminds me of the arm you attach to an ironing board to keep the cord from tangling, but that’s obviously not right.

The dimensions are somewhat important, because of the labeled diagram on the left. Fig. 3 is also significant but it’s unclear how it relates to the rest of it.

It looks like it should hold something, but you can’t hook anything over that upper part.

So I’ll have to admit to being completely stumped this time. Since you said it’s related to SE Michigan, I’ll say it’s a boat hook for pulling in loads of Prohibition rum across the Detroit River from Canada.

I cheated. Then I didn’t comment. At first glance, I thought it was a whip of some sort. Not being able to tell materials..

“Indian corn” is maize. Before the 1800′s, “corn” was a more generic term for any kind of cereal grain: wheat, barley, maize, or rye. In the US and Canada, and later Australia, usage evolved, and corn came to mean only maize (maybe because we grew so much more of it than other grains?). In the UK “corn” may still refer to cereals generally, though I think the usage might be shifting there too. By the way, this helps explain “corned beef” — beef that was cured in very coarse-grained salt.

When I was a kid, we used “Indian corn” specifically to refer to multi-colored “calico” corn, as opposed to the yellow sweet corn we ate (I don’t think anyone ever thought of eating “Indian corn,” though it’s theoretically edible).