In the Archives: The Friendless Dead

Willie Brown ended his days among strangers, his body submerged with theirs in a large vat of preservative liquid in the basement of the onetime University of Michigan medical school that stood on the east side of the present-day Diag.

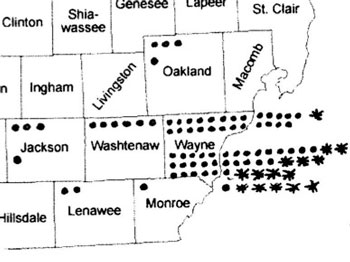

Origin points for each of the over 100 cadavers donated to the UM in 1881. (Map compiled by the writer from Anatomical Donations Program records. Image links to complete map.)

The 22-year-old had never married or had children. If he kept a diary it apparently was not preserved in a public archive. His parents were from New York state, but even this meager detail was forgotten by the author of his death certificate. Willie was a hired farmhand, without distinctions like membership in the Pioneer Society of Washtenaw County. That group counted as a member his employer, successful veteran Pittsfield farmer Jefferson Rouse.

Ignored in life, Willie commanded intense attention after death from the medical students dissecting his body. They examined and took notes on the body that had helped shear Rouse’s 350 sheep, tend his dozen pigs, and harvest the hops, potatoes, apples, wheat, and Indian corn on Rouse’s 560 acres between Saline and the present-day Ann Arbor airport.

The students may have dissected Brown’s lungs to look for signs of the tuberculosis that killed him. When Willie got sick, he apparently wasn’t cared for on the farm, at least not for long. He went to the county poorhouse, at what is now the southwest corner of Washtenaw Avenue and Platt Road. There among the other nearly 70 residents in 1881, he died.

No friend or relative claimed him, and he wasn’t buried in the unmarked poorhouse cemetery just west of the poorhouse. His body was placed on a wagon that traveled from the poorhouse up the dirt road of Washtenaw Avenue to the medical school. Medical science owed Willie’s contribution to a new 1881 state law that strengthened the up-till-then largely-ignored proviso that the bodies of the unfortunate could be legally delivered to the UM for study.

The medical school as depicted in Andrew McLaughlin’s 1891 book “The History of Higher Education in Michigan.” The left side of the building is facing East University Ave.

A similar proviso had entered Michigan law as early as 1867, as “an act to authorize dissection in certain cases, for the advancement of science.” It allowed that local officials could donate the bodies of deceased prisoners or “such persons as are required to be buried at the public expense . . . preference being always given to the faculty of the medical department of the University of Michigan … ” This proviso was cancelled if the dying person requested a burial or if a relative or friend claimed the body within 24 hours.

Despite the law, and two slightly-altered reiterations of it in the 1870s, the public’s general distaste for dissection, in lieu of a decent and Christian burial, led many to claim to be a “friend” of a friendless person, and recover the stranger’s body for burial.

This helped cause a chronic shortage of anatomical specimens at UM, leading to the university’s well-known under-the-table dealings with shady “resurrectionists” in order to obtain bodies. These deals were performed out of necessity and far less cavalierly than is often sensationally portrayed in histories of the medical school.

The university’s ties to grave-robbers were known in the 19th century, and social censure weighed upon those in the anatomy department. In 1880, the “Demonstrator of Anatomy” in charge of procuring bodies was William Herdman. He complained at a June 28, 1880 UM regents meeting.

Herdman spoke regarding the “recent and remote instances of grave-robbing which have come to your attention and to the notice of the public … which have justly excited indignation on the part of all law-abiding citizens and have been the cause of great annoyances to all friends of the University and especially to you, [the regents] … ”

Herdman asked the regents to consider the difficulty of his responsibility to obtain 90 to 100 anatomical specimens per year for the medical school. His method, he told them, was to exhaust all legal means of obtaining bodies first, and when in special need, “to draw from the pauper and friendless dead at our county-houses and asylums with the consent of the proper authorities if such consent could be obtained … [i]s it therefore asking too much that [the pauper's] body, unclaimed by friends, cared for by none, useless to himself, be made to contribute to the welfare of his fellows who have given freely of their substance to provide for him in comfort and health during his natural life?”

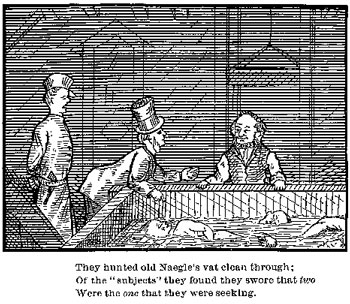

The December 1878 UM student-produced magazine the Palladium included a comic strip satirizing William Herdman and his helper Patrick Naegle. The strip references a 1878 incident in which the body of one Augustus Devins, buried in Ohio, mysteriously surfaced in the basement of the medical school. The two gentlemen at left are out-of-state officials seeking Devins’ corpse.

“Though not strictly legal, I have endeavored … to secure this pauper material from different parts of our own state for dissection,” said Herdman. “You know full well the character of many of the men we are compelled to employ in this clandestine business.”

Herdman’s unsavory task was made easier by the 1881 law. The original 1867 act had mentioned only prisons as possible sources of specimens, with an additional vague reference to those in the community who died without financial resources. But the 1881 act built upon 1870s amendments to clearly specify that the deceased in poorhouses, workhouses, jails, or any charity supported by public funds could legally be sent to the UM. The UM would be in charge of distributing the bodies equally among three schools: the UM, the Detroit Medical College, and Detroit’s Michigan College of Medicine.

One of the 1881 law’s requirements was that detailed records be kept of each body donation. The ledger that lists, in a graceful and careful hand that is likely Herdman’s, the 1881 donations to the University has survived to the present. It shows that 108 bodies were donated to UM in 1881 from poorhouses throughout the southern half of the lower peninsula. The greatest number came from Wayne County, which had a poorhouse, prison, and insane asylum. The furthest came from Big Rapids in Mecosta County, about 130 miles as the crow flies.

No bodies came from north of a horizontal line extending from Bay City westward to Big Rapids. Few poorhouses existed [map] in the less-populated northern lower peninsula, with only 3 in the U.P. In addition, the enforced waiting time for body identification plus time spent packing and shipping the deceased by train brought into play sanitary considerations.

Willie Brown was the first recorded donor, in August of 1881, from the Washtenaw County poorhouse. Over the remainder of that year, five more bodies from the county poorhouse made the journey up Washtenaw – those of 38-year-old Stephen Pomare, 58-year-old Wesley Freer, 49-year-old Edward Cresson, 38-year-old Charles Williams, and 25-year-old Pat Monahan.

The afflictions that killed these five men were sunstroke for Pomare and Freer, tuberculosis for Monahan and Cresson, and a fistula for Williams. The men were relatively young, but mortality rates at the poorhouse were over 10 times higher than in Washtenaw County as a whole. In 1880, the county had 41,779 citizens with an additional 66 (at census time) in the poorhouse. The county suffered 496 deaths that year, or just over 1% of its population; the poorhouse saw 9 deaths, or 14% of its group.

Some county residents lost their livelihood due to illness, and entered the poorhouse with a pre-existing condition. In addition, 1880s-era Michigan poorhouses were by and large unhealthy environments. Many consisted of poorly-repurposed farmhouses or hotels and the majority lacked bathing facilities. Crowding of inmates, some with then-poorly-understood communicable diseases, was common. The general atmosphere could be disturbing or depressing as well, as those with physical and those with psychological disorders were often housed together. Sufferers of mental disorders were in some places treated gently and humanely and involved in activities, and in other locations, or in severe cases, were confined in locked cells. In one Ingham County case, state inspectors found a mentally ill resident chained to an outdoor fence.

Found a man of about 24, idiotic, said to be inclined to escape, and so tied, without shelter, to a fence near the house, where he had worn a path at the end of his rope, like a chained animal. The effect upon other inmates, of constant exhibition of a human being in this condition, chained like a bear to the fence, must be to degrade and brutalize. Upon suggestions made to the superintendents to the poor, he will, no doubt, be differently cared for hereafter. [Biennial report by the Michigan State Board of Corrections and Charities, 1881-82.]

Washtenaw’s poorhouse was one of the state’s best. It offered bathing facilities with a requirement to bathe once a week, adequate clothing year-round, a Protestant and a Catholic chapel (any chapel was a rarity among poorhouses of the era), and a varied diet, much of it drawn from the 119-acre poorhouse farm. Some inmates helped slop the 11 pigs, feed the 80 chickens, and milk the farm’s 8 milch cows. They picked peaches and apples, and tended the wheat, oats, and Indian corn. The farm sold many of these products, helping offset the weekly average maintenance cost of $1.25 (about $30 in today’s dollars) per resident.

The original poorhouse building and farm are long gone. The cemetery remains unmarked and is at least partially covered by Washtenaw Avenue. The residents’ names are largely forgotten. The final contribution of some of these weakest and humblest of onetime county residents helped to strengthen and make prominent the name of the University of Michigan.

One small part of that luster is due to a 22-year-old farmhand, someone’s son, who thought, dreamed, laughed, and worked the fields over 130 years ago.

Mystery Artifact

The last column’s Mystery Artifact featured a floating barrel meant for a carp pond.

The device was, as Tim Durham correctly guessed, meant to be a beaver trap, meant to safeguard one’s home-made dams. Great guess, Tim!

This time we come closer to home with an artifact one could easily have found in the olden days in Ann Arbor. It’s an odd little shape from an almost completely vanished trade. It also has a forgotten and specific name – who knows it?

Last time Tim was the last to guess, but the first to identify the beaver trap; sometimes a guess that’s last is correct! Good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Hidden Ypsilanti” and “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Contact Laura at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to keep readers up to date on the quick and the dead. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

I believe this is a tool a cobbler would use to make shoes and or boots. It is referred to as a last. This one appears to be cast iron but they were also made out of wood. There is a quaint but excellent book “Every Lady Her Own Shoemaker” which describes how to make a basic women’s shoe of the time.

Rebecca: Thank you for reading, and guessing! That book sounds interesting. I note that there regrettably are no copies on Amazon, and the nearest library copy is at the Henry Ford: [link]

Perhaps I missed it, but wasn’t the location of the poorhouse the present County Farm Park and the rest of the county property at Washtenaw and Platt? And in fact isn’t that the source of the name County Farm?

Interesting that two uses nominated for the Platt Road facility being vacated are affordable housing and a community garden or farm.

Yes indeed Vivienne, you are correct. And that is an interesting tidbit; thank you.

Shoe last is a good guess, but I can’t find any pictures of old ones that look like this. It’s also too small. A woman’s shoe with a 7.5 inch last would be a size 1.5.

Laura – you can get a copy for a very reasonable price from Amazon Drygoods. Or ask any re-enactor for a loan….

Mr. Rees – Please remember that women’s shoes are sized very differently from modern times. And people were smaller. Short feet are not a crime – my feet measure less than 9″. And I wear a size 6 (women’s).

Welcome back, Laura! It’s good to see your always fascinating posts back in the Chronicle.

Jim: Interesting guess…it is quite narrow, too.

Rebecca: Ah, thank you for the tip. It’s always interesting to read about old trades and skills. Thanks!

Tom: Thank you for your kind words; I’m glad to be back!

Now, the University’s Medical School has a carefully regulated Anatomical Donation Program, through which you can make arrangements to donate your body for use in science and research (once you’re done with it). You can even arrange for it to be used temporarily, then cremated and your ashes passed on to family. [link]

George: it’s mind-boggling to imagine how many people have been saved or helped via research because of that program: literally tens of thousands of donors have contributed to date.

I agree that it looks like a last. Seven inches would be small for a modern adult, but it’s an entirely reasonable length for a child’s shoe today.

As a volunteer for the Gen. Soc. of Wash. Co., we were wondering were we might obtain the names of all of the 108 bodies donated to UM in 1881. We often get genealogists requesting information about Washtenaw County residence. Thank you for the informative article.

Kathy: It’s valuable information, to be sure! I am sorry to say I didn’t transcribe all of the names in a complete list–I just made notes on bits of information I wanted to use. I probably will go back to the Bentley some time after the turn of the year and transcribe the information, ideally into Excel on the laptop. When I have that information, I’ll definitely send the GSWC a copy!