In the Archives: Ypsi’s Submarine Diver

Editor’s Note: On April 20, 2010, an explosion on an oil rig 50 miles off the Louisiana coast left 11 workers missing and presumed dead. Efforts are now focused on the underwater challenge of trying to cap off the oil well on the sea bed. Local history columnist Laura Bien takes a look back 150 years into the past to recall a Lake Erie underwater challenge resulting from a different tragedy.

In the summer of 1852, $36,000 in cash and gold bars lay in a locked safe 165 feet deep on the floor of Lake Erie.

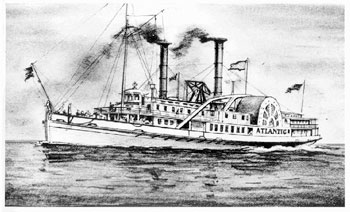

Worth $920,000 today, the riches lay within the wreck of the steamship Atlantic. So did more grisly testimony of the shipwreck’s victims, estimated as ranging from 130 to over 250. The deaths represented about a third of the 576 travelers packed onto a steamship meant to accommodate far fewer.

The era’s stream of immigrants pouring west made a profitable trade for passenger steamers traveling the Great Lakes. The Atlantic was the fastest one of all, speeding to Detroit from Buffalo in just 16-and-a-half hours. A towering steam engine churned huge paddlewheels on either side of the vessel. Despite her power and 267-foot-long brawn, the Atlantic succumbed when she was struck on the night of Aug. 20, 1852, by the Ogdensburg, a ship from a rival ferry line.

In the chaos and panic that ensued as the Atlantic began sinking, several of the lifeboats swamped when they hit the water. Some passengers grabbed cushions or anything buoyant and jumped in the water. The Ogdensburg circled back and picked up about 250 survivors from the water.

Immigrants among the rescued traveled on into the new world with no possessions, and some, according to survivor Amund Eidsmoe, one of the 132 Norwegians on board, went in a half-naked state to Milwaukee. In that city, a collection was taken up for their benefit. Eisdsmoe received $30 and a suit of clothes.

Another of the surviving Atlantic passengers wrote a letter home to Norway that included a newspaper account presenting the incident as sabotage by the Atlantic’s captain. The heads of the two steamship companies went to court in a case that ultimately was decided by the Supreme Court, which ruled that both vessels had been at fault.

The gold remained at the bottom of Lake Erie. Several divers tried, and failed, to get it. The treasure lay deeper than it was thought anyone could dive.

Elliott Harrington tried in 1856.

Born in Westfield, N.Y., just a few miles from Lake Erie, Harrington had previous experience in Michigan – attempting to recover the body of a farmer from an inland lake. In 1855, Scio Township sheep farmer William Briggs drowned while washing his sheep in a small lake near his property.

“All efforts to recover the body being fruitless,” reported an early June edition of the Ypsilanti Sentinel, “Messrs. Harrington and Philips were sent for to search with their submarine armor.”

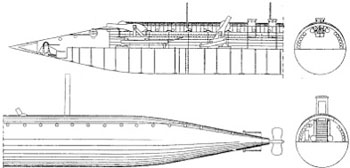

Harrington’s partner, Lodner Philips, was a Michigan City, Ind. shoemaker who invented and built submarines – one 85 feet long – in his spare time.

The paper continued, “[T]hey made numerous descents, at various depths, discovering most singular irregularities of bottom, and curious formations. In some places the plummet will strike bottom in a short distance. A few feet off, down it goes to an almost unfathomable depth. Sometimes upon arriving at what seemed to be the bottom, the diver’s feet rest upon nothing, and down he goes into impenetrable darkness and a soft mass of mingled water and sediment, until prudence warns him against further progress.”

Harrington’s efforts were not successful – the body was never found. Still, a gravestone for William Briggs stands in Ann Arbor’s Forest Hill Cemetery.

A one-time lake adjoining Briggs’ former property in section 34 of Scio Township is no more, except for several tiny ponds. Houses and a subdivision occupy the site, at the southeast corner of West Liberty and Zeeb roads.

A year after the Briggs search, Harrington dove for the Lake Erie treasure from the Atlantic.

Philips had already tried, and failed, with another submarine of his that he called the Marine Cigar. It was nicknamed the “Fool Killer.” On an unmanned test dive to the shipwreck, the sub was lost. It rests today with the Atlantic in Lake Erie.

The sub was one of the sights Harrington saw on his own attempt. Others were described in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of July 12, 1856.

“A submarine diver from Buffalo has at last succeeded in raising the safe of the American Express Company, which was lost when the steamer Atlantic was sunk off Long Point, in 1852 … The diver was protected by copper armor, and was under water forty minutes, during which time he had some strange adventures.”

The paper continued, “When the diver alighted upon the deck, he was saluted by a beautiful lady, whose clothing was well arranged, and her hair elegantly dressed. As he approached her, the motion of the water caused an oscillation of the head, as if gracefully bowing to him. She was standing erect, with one hand grasping the rigging.

“Around lay the bodies of several others as if sleeping. Children holding their friends by their hands, and mothers with their babies in their arms were there.”

Harrington found the safe in the ship’s office, maneuvered it to the deck, and attached chains. He and the safe rose to the surface.

The safe contained five thousand dollars in gold and $31,000 in cash. Harrington ultimately lost all but a fraction of the money in court.

Perhaps out of pique, Harrington then moved to Iowa with his wife Emaline and his children William, Forest, and Allie. The 1860 census lists him as a carriage maker in St. Charles Township in Floyd County, Iowa.

He served with the Union Navy during the Civil War. Harrington allegedly had a Confederate price on his head ranging, various sources say, from $5,000 to $8,000 because he discovered the gap in the Union naval blockade around Charleston where Confederate blockade runners were slipping through.

He survived the war and moved back to the Great Lakes area, settling in Ypsilanti. He resumed his profession of submarine diving. The family lived in one of the nicer homes on Prospect Street near Prospect Park. Later it appears that he moved to Detroit and that Emaline died there.

Harrington’s father had died in 1872, and his mother in 1878. They are buried in the Volusia cemetery near Westfield in New York. After a lifetime of excitement and adventure (except maybe for Iowa), Harrington ultimately returned home. He died there on his birthday – April 19, 1879.

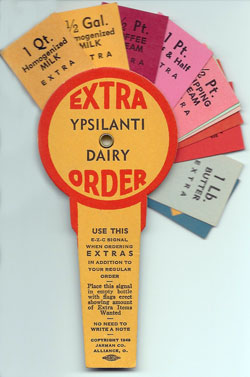

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

Last week Lisa Bashert correctly guessed that the M.A. in question was a child’s bicycle seat. The lack of context made the item somewhat tough to figure out.

To compensate for that, this week’s Mystery Artifact is a bit easier. Made of paper, this 6-inch-long item has a movable fan of tags on top. How was it used? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales of the Ypsilanti Archives,” available on Amazon and at local stores. Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

Maybe I’m missing something, but I think it says right on the item what it is? It’s for extra dairy items in addition to a regular delivery.

“Ypsilanti Dairy Extra Order. Use this E-Z-C [easy see?] signal when ordering extras in addition to your regular order. Place this signal in empty bottle with flags erect showing amount of Extra Items Wanted. No need to write a note.”

cmadler – I believe you are correct but forgot the magic word. One would place this in their ‘milk box’ (that great little pass-through box with an inside and outside door) along with their empty bottles so that the milkman could supplement your usual delivery order.

Calder Farms still delivers! I have to wonder how many milk boxes are still in operation.

Interesting comments cmadler & ABC.

ABC: wouldn’t it make an interesting photo essay to photograph any of the remaining milk boxes around town? Are there any?

I suspect there are not many left. Decades ago people began to substitute less cool metal boxes that sat on the ground outside of the back or side door because the through-the-wall version leaked lots of air. Even when houses were not insulated this was a weak link. I’ll bet there are still some around hiding behind new siding and stuffed with fiberglass.

Tidbit from Wikipedia: “1856: Lodner D. Phillips, designs the first wholly enclosed ADS. His design comprised a barrel-shaped upper torso with domed ends and included ball and socket joints in the articulated arms and legs. The arms had joints at shoulder and elbow, and the legs at knee and hip. The suit included a ballast tank, a viewing port, entrance through a manhole cover on top, a hand-cranked propeller, and rudimentary manipulators at the ends of the arms. Air was to be supplied from the surface via hose. There is no indication, however, that Lodner’s suit was ever constructed” [link]

So submarine building and diving overlapped, in that the deep water suits were kind of like submarines with arms and legs.

We had a “milk chute” as we used to call it, in a house we rented when I was a child in the 1960′s. The house was on Evelyn Street in Ypsilanti and the next door neighbor was a Twin Pines milkman. The “chute’ was also used to pass a small child through when Mom or Dad locked the door and forgot the keys.

ABC: Yes, I was thinking that having a big “open” box in one’s home would not be too nice in winter. I wonder if any got covered with siding on the outside but still have the little door on the inside; I’d love to see one.

Fritz: That is cool; I think I saw a pic of that somewhere in the research period…it looked very like the robot in Lost in Space, minus the glass…head…pod…thing.

Ah, here it is (scroll down through some other great pics of his inventions): [link]

Dave: That is a wonderful image, passing the child through the chute. So that’s one chute documented, on Evelyn Street in Ypsi. Very neat.

The house I’m renting has a milk box. It’s nailed, caulked, and painted shut inside and out though. The door inside doesn’t feel cold in the winter compared to the wall around it, so I’m guessing it’s been insulated, too.

Adam: That’s very neat. I wonder if they *were* insulated, so as to protect the cool milk. Hmm…

I remember having milk delivered to a insulated metal box on Summit St in Ann Arbor in the 60′s. Milk was delivered in glass bottles

That’s very interesting, Zanzerbar; so they were, or some were, insulated. I love learning about the details; thank you!

My favorite milk door was the one at the Ann Arbor Animal Hospital, when it was still an old house. They had walled off the original porch to make a waiting room but left the milk box set in the wall, in which there was a clear plastic anatomical model of a dog on display. Always fascinated me.

i used to live in a complex built in the early 60′s that still had the outside milk doors intact, because there was no way to patch over the brickwork. There are probably a lot of similar places to be found if you look hard enough.

We had milkman when I was a kid in the 60s–Mr. Fitzgerald–who would just walk in, put the new bottles in out refrigerator, grab the old bottle, maybe chat with whoever might be sitting at the kitchen table, and leave. We never locked our doors, so I guess our whole kitchen was the milk chute. I remember when he stopped coming, I couldn’t figure out how we were going to get milk–I didn’t know you could even buy it in stores.

My wife grew up on Hatcher Crescent in Ann Arbor, and she says all the houses in that neighborhood had them. I bet you could still find some there–visiting that neighborhood is like traveling back in time.

Cosmonican: that is a wonderful example, and a vivid image of the dog…the hospital is on W. Liberty now; I wonder if the old site still exists.

Rod: That is an evocative memory of a very different time…can you imagine how someone might react today to someone just strolling into the house? That’s a good tip about Hatcher Crescent off Miller. Thank you for the name, too: Mr. Fitzgerald.

One more for Cosmonicon: I was very interested to read that the milk doors were installed in a complex built in the 1960s. That is much later than I imagined that builders would still take pains to create this special structure–I imagined that milk delivery was on the wane to some extent by then, with the rise of supermarkets and home refrigeration. Also because my own home was built in 1948, yet has no milk door. However it is in a sub of extremely tiny homes built near Willow Run and mostly for the influx of returning GIs–cheaper housing, so I imagine homes in this neighborhood just put bottles on the porch.

To clarify for Laura: The house with the Animal Hospital was torn down to make room for their new facility (near Stadium & Liberty). The complex I mentioned is in Southfield, but there are similar types around here, it was built around 1963; for comparison, the houses on Hatcher Crescent and the surrounding neighborhood date from roughly 1954 to 1959.

Along Miller Ave, and several blocks north, there were small groceries like Knight’s that existed up until the late 60′s. I remember one at Miller and Brooks, one at Miller and Chapin, a block north of Miller on Fountain, and one way up Spring Street. There was even a shack in the vineyard where the city park is now at Sunset and Vesper where an old lady sold magazines, gum and cigarettes from time to time. If you didn’t have a milk box, it wasn’t a long walk to get milk and eggs if you needed them. I think a lot of neighborhoods around town had little stores like that for staples.

The house I grew up in near Buffalo still had a milk box when I left there to come to the University in 1950. I was put through it as a child to open the door and I once repeated the act as a locked out teen ager.

In Ann Arbor I recall home milk deliveries to a house on Greenwood where I lived as a student in 1953. A house built in 1958 that I later owned on Gralake also had a milk box.

I grew up in West Michigan in the 50s and 60s. Our milkman’s name was Ray and he delivered for Hansen’s Evergreen Dairy in Scottville, Michigan. We had the aluminum insulated milk boxes but because we were out in the country, we didn’t have a milk chute. The bottles were glass, of course, with paper tabs in the top. The best thing (besides the Golden Gurnsey milk with the cream on the top) was riding in Ray’s milk truck down the road to our cousins house. As there were no doors or seat belts, it made for an exciting ride.

It didn’t say anything about a milk “box”. The tag clearly stated that it was to be put in the milk “bottle”. The copyright date is too blurred to make out, but I believe this was before the ‘milk box’ of more modern times was developed. People used to leave their milk bottles on the stoop or porch to be collected and replaced with fresh ones and this tag was used in case ‘extra items’ were needed in addition to the usual order, whereas they used to have to leave notes in the bottles informing the milkman of their additional requirements. As far as I can tell, the milk chute was developed in the 30′s but I cannot state that with 100 % certainty. Prior to that most folks just left the bottles on the porch for the milkman to collect and replace.

55 years ago, at age 10, I rode as a “jumper” in my stepfather’s Sealtest milk truck for a summer. Oh yes, almost all houses had milk chutes. And wasn’t it fun during summer when one of us would open the outside door of a customer’s chute to be greeted by: a large hornet nest inside!

Oddly the house we lived in at the time lacked a milk chute. But the house we moved to (about 1 mile away in the “city”) did have one. The inside door of the chute never seemed cold in winter: maybe it was because the warm inside air was flowing outward (?).

It certainly seems odd now: people wanting to see this quaint contraption. If only we could predict the future: some items like this could be preserved (at least in photos). Possibly, it might be a good idea for everyone to take pictures of things we now take for granted as “permanent.” Like for instance: the family car.

One thing not mentioned so far is that these milk chutes (or the alternative porch) had no refrigeration or insulation. This “system” of home delivering dairy products worked on a primitive level with one underlying assumption: there would be someone home during the day to take the delivery and put it in the refrigerator. That is, subscribers were almost always married home owners (with or without children). It would be the woman who stayed home – that’s the assumption I mean.

I never saw such a pre-made “extra items” device as depicted. Instead: if my stepfather’s customers wanted something extra: they just stuck a rolled up hand written note in the neck of a milk bottle. I remember those notes: taking them back to the truck and having my stepfather put the additional items in the “milk carrier” basket which I then had lug back to the house and leave with the original order.

Elliott Harrington’s story about seeing corpses appearing is if they’d died within hours or days of his arrival is, to say the least, highly suspect. If indeed he reached the wreck of the Atlantic at all, any corpses would have been in much worse shape and in much less “lifelike” poses than described. That’s even granting the fact that the cold water would have delayed decomposition. What would have happened is that fish and other creatures would soon have begun feeding on the corpses.

As one who once served sheriff’s departments in body recovery efforts and whose father “brought up” a dead body that had been sunk in cold water for a couple of weeks, I can assure that such corpses are nightmarish in appearance. I have the nightmares to prove it. So – either Harrington made this up so as not to upset relatives of those lost or the writer of the newspaper article did it for that or similar reasons.

A related item to the pass-through milk delivery chutes–coal chutes. The coal chute was a heavy metal door on the driveway-side, or front of the house that allowed a coal delivery vehicle to tip a load of coal down a trough, through that opening, into the basement of the house. My folks’ house on the outside edge of the Old West Side of Ann Arbor has one (though the inside was long ago covered over). I’ve seen identical items on many houses.

Until my folks replaced their old furnace–an ‘octopus’ style (because it had many, large, circular ducts–though maybe not eight such), gravity operated (because the hot air rose up through the ducts, rather than being blown) model–the furnace ‘front’ had the multiple doors that allowed shoveling in coal and adjusting the airflow so as to keep the coal burning at the proper rate.

But a drawback to these delivery ‘chutes’–a neighbor family’s home was burgled (may years ago) by means of reaching or crawling in through a milk chute. The saddest aspect of that story: it was likely a neighborhood kid/youths who did the deed, as the chute was known to kids who visited/played at the home, but hidden from street view. Covering over such items makes sense for more than just insulating against cold weather.

Steve H. reminded me of an ugly incident. We had a coal furnace converted to oil, and the oil was delivered through pipes in the old coal chute. There was one pipe for the main tank, and one for the reserve. The delivery guy got the wrong pipe, and we ended up with 300 gallons of #1 fuel oil on the basement floor — the house smelt like what the gulf must now, and what a mess!

Also–might be interesting to compare cisterns to rain barrels.