In the Archives: Pulling a Tale out of the Hat

Editor’s note: We belatedly note that two months ago, in January, Laura Bien completed a year’s worth of her bi-weekly history columns for The Chronicle. We’re looking forward to the next year of her looks back into the archives.

He was born on the eve of the World War, a tiny baby with a fine fuzz of hair. Mac was tenderly cared for and quickly put on weight, soon growing to be a healthy, bright-eyed youngster playing in the grassy backyard.

The large home at 304 Washtenaw Ave. (at Adams Street) held two generations of the MacVicars, one of Ypsilanti’s many families of Scottish descent.

The 51-year-old widow Loretta shared the home with her three children: 22-year-old James, who was about to move out West with his University of Michigan electrical engineering degree; 27-year-old photograph retoucher Adelaide; and 29-year-old Malcolm, who worked as a traveling salesman for an optical company. It was a job title he shared with two of Loretta’s 50-something brothers, also residents in the house. In addition, three lodgers rented rooms there.

Malcolm carefully fed and cared for Mac. As he grew up, the little one didn’t have the slightest conception of the plaudits and fame that lay in days ahead, after the war. He could not imagine his eventual, and lucrative, popularity with the ladies. He never thought of the future.

That’s because Mac was a bunny.

In 1917, Malcolm the optical salesman spent most of his time on the train, traveling to the next town to demonstrate his employer’s optical products. As the slightly swaying train clacketed over the rails, the young man – of medium build and height with light brown hair and dark brown eyes – passed the hours reading and gazing out the window at the fields, hills, and farms sliding by.

He missed Mac.

Beside him on the seat lay his suitcase-like sample case, tightly packed with a large assortment of golden frames, several delicate silver pince-nez, an optometrist’s lens device, spectacle repair kits, and literature about his employer.

Based in Omaha, Riggs Optical had dozens of offices across the Midwest and West. The company manufactured lenses, spectacle frames, and eye testing equipment for optometrists. The company’s success – it would survive until a 1999 buyout by Bausch & Lomb – likely depended in part on its marketing savvy. Many ads from competing optical companies were comparatively bland.

One vintage Riggs ad urged optometrists to recommend that their patients purchase more than one pair of glasses. The ad showed a picture of a swanky top hat next to a bag of golf clubs. “When we study the varied activities of the average person,” it read, “we realize that seldom will a single pair of lenses fulfill the optical needs of that person.” Another ad for “Orthogon Bifocals” argued that older customers, less active than younger ones, depended more upon vision for the quieter pursuits of old age.

During Malcolm’s travels, on May 18, 1917, Congress created the wartime draft. Malcolm stepped off the train in Worth County, Iowa and headed to the draft office to register. He’d spent three years at New Jersey’s Montclair Military Academy, where his Uncle John had taught, and at age 30 just fell within the draft’s age range of 21-30.

Malcolm’s 22-year-old brother James, who had just moved to Los Angeles to work at Universal Films, registered in early June. On his draft registration card, he wrote that he should be exempt because he financially supported his mother and sister.

Despite Malcolm’s military experience and James’ plea for exemption, it was James who was drafted. He served in a field artillery unit, and in time came home uninjured. Malcolm appears to have used the war period to earn a law degree. In this he followed in the footsteps of his well-known and widely-admired grandfather – educator and author Malcolm MacVicar (pictured above), who served as the president of Ypsi’s Normal College a few years before Malcolm was born. As a newly-minted lawyer, Malcolm would no longer have to wait in chilly mornings at tiny towns’ lonely depots, peering down the tracks.

Both MacVicar sons returned to live at 304 Washtenaw. James worked as a car salesman, and Malcolm practiced law.

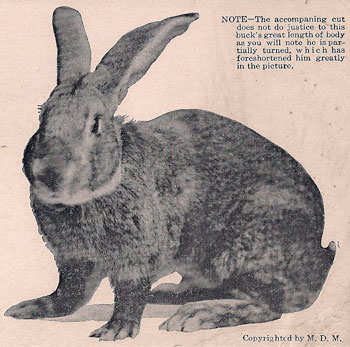

He also practiced the selective breeding of pedigreed rabbits. His star male rabbit Mac carried the full name “MacVicar’s Clansman,” in honor of Malcolm’s Scottish heritage.

Malcolm specialized in the Flemish Giant, the largest standard breed of rabbit. Flemish Giants can grow beefy bodies a yard long (not counting legs) and weigh up to 22 pounds or more. These bruiser bunnies luckily tend to have mellow, affectionate natures.

In the summer of 1919, Malcolm was preparing his stable of bucks and does for the upcoming exhibition season. He was proud of his brawny flock and decided to have them professionally photographed at Rentschler’s Studio in Ann Arbor, where his sister Adelaide worked. He piled seven big bunnies into the car and headed to Ann Arbor.

In the Huron Street studio, three of the does, Calamity Jane, Mission Chimes, and Pomona posed for a group portrait. The others each received their own individual sitting: MacVicar’s Clansman and the does Esther May, Minerva Ann, and Princess Joan. During each shoot, the other rabbits slowly galumphed around the studio floor, exploring, weaving under the camera tripod, and snuffling behind the hanging backdrop whose faded paint depicted a garden scene. One disappeared into a back room.

Malcolm copyrighted the photos and included one on a large promotional business card for Mac that he commissioned at a print shop. He then packed up Mac, cards, and supplies and headed for an animal exhibition and judging show in Holland, Michigan.

At the show, Mac was examined by the rabbit judges. The length of his body was measured: one inch short of a yard. They weighed him: 16 1/4 pounds. His body showed the breed’s desired “mandolin” shape, with a rounded rump. Mac was alert and calm, his coat a smoky steel color under the electric lights. The judges conferred, and awarded him two prizes: First Senior Buck and Special Best in Show.

At the Detroit show, Mac did even better. No less than Charles Gibson, whom one admirer called a “staunch old pioneer in Rabbitcraft,” extolled Mac’s beauty. This well-known author of “Breeding and Care of Rabbits for Exhibition and Market” examined Mac closely. “MacVicar’s Clansman is the most wonderful specimen of gray Flemish bucks I have ever had my hands on,” he was quoted as saying. “He is the best gray buck in this country today east of the Rocky Mountains and including Los Angeles, and the equal of any gray buck ever shown in San Francisco at any time in the past.” Mac won three awards in Detroit, the Challenge Cup for Best Flemish Buck, the First Senior Buck, and the Special Best Gray in Show.

Mac’s newfound fame made him very desirable as a stud bunny. Malcolm marketed Mac’s charms and carefully screened potential partners down to a “limited number of approved does,” as Mac’s business card said. For each tryst, Malcolm charged $12 – $150 today – in a time when the going rate for a brand-new pair of Flemish bunnies was $4.

Between the fresh, tasty veggies and hay, the cosseting, attention, and pets, and his obligatory dalliances, Mac had about as good a life as anyone could wish for. Flemish Giants usually live from 4-6 years, but occasionally survive into their teens. If the pampered Mac lasted that long, his happy life could have extended into the 1930s.

Long after his death, his handsome likeness on the decades-old business card remains with us as a memorial, now stored in the Ypsilanti Archives. The eminent MacVicar’s Clansman had done as much as any bunny could do to bring honor to his human family and a measure of fame to his hometown.

Mystery Artifact

Among the many good guesses, only one lone person correctly guessed last column’s mystery artifact: the beautiful cast-iron housefly is a safe for matches.

(Wow, good call, Barbara; that was a toughie!)

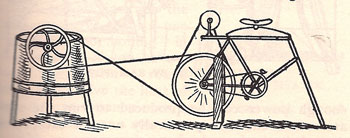

This time we’re venturing into the realm of ol’-timey DIY to examine this curious doodad. What on earth is it? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and the upcoming book “Hidden Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

I’ll guess that it’s a bicycle-powered washtub. Or a butter churn, an ice cream churn, or just about anything else that would rotate in such a manner as that.

New timeys can learn from ol’-timeys: [link]

Re: [1] “I’ll guess that it’s a bicycle-powered washtub.”

I’m skeptical that it’s for washing clothes. For one thing, that would be way too easy. For another, it leaves unexplained the extra wheel — near the location of what would be the handlebars. At first glance, it appeared to me that it’s a way to hand-crank and pedal the apparatus. But that doesn’t seem consistent with the apparent ratio step-down for the revolutions. If you were pedaling and and trying to hand-crank at the same time, wouldn’t your shoulders fly out of their sockets? So I’ve come tentatively to the conclusion that it doesn’t depict hand cranks, but something like a grind-stone, so that the operator can sharpen knives or something while the tub rotates. I would think that whatever activity the operator does right in front of them would be related thematically to what’s going on in the tub. But I don’t get why the direction of the rotation of the tub would need to be reversed, so I’ve concluded that this is somehow key to the correct explanation.

Interesting guess cmadler; we’ll see.

Hmm, lots of interesting speculation there Dave…yeah, that extra wheel is kind of tricky, hmm…

abc: I remember when Dave invented that: at the time I thought that was mighty darn cool (still do). I admire that can-do ingenuity overcoming a dependence on energy.

“Stud bunny”?

I, too, was reminded of HD’s laundry spinner, but I think this one is a butter churn.

Joan: Yes, ma’am…”stud bull,” “stud dog,” &c. :)

Dave

You seem to understand gears better than I do. Could the ‘grinding wheel’ (small wheel) be a way to hand turn the ‘washer’ slowly and the larger wheel (connected to pedals) be a way to turn it faster? Does butter churning require faster and slower speeds?

The faster-and-slower speeds theory might actually be consistent with a washer. The washing goes better at slower speeds and the spinning goes better at higher speeds. But I do not want it to be a washer. Because that would mean someone already thought of this long long ago. So let’s please figure out what it must have been besides a washer.

Obviously the small wheel is part of an odometer assembly, note the offset where the side of the belt closest to the seat goes near the hub, while the other side of the belt enters or emerges closer to the outside of the small wheel.

The larger belt operates a differential gear causing the cylinder to spin at a high rate, and with the help of a lantern within the cylinder operates a zoetrope type device, thus entertaining the operator of the exercise bike and keeping track of their progress, much like TV/Stationary Bike setups found at modern clubs. Does that help, Dave?

I read the comments. I still think it’s a washtub. I don’t think that thing is a handle. I think it’s the seat. I think the perspective is off since it’s a one dimensional drawing. I think the long line is a spring, like you’d see on a wagon or buggy and the short bow tie looking thing is the seat and that it’s sitting across the long spring like the bar on a T

I could see it being an ice cream churn as well, for a church social or some such. But I still lean toward wash machine.

Irene

Cosmonicon: I love zoetropes and all the related proto-movie type devices popular in the 19th century. I saw an art installation in AA a few years ago consisting of large (washing machine-sized) modern hand-welded zoetropes whirring and clacketing away–so beautiful and entrancing. There’s also that one (N.Y.?) guy who made a type of zoetrope using a long wall with slits installed in a subway tunnel, with the gradually-changing images behind the wall.

Lots of interesting guesses thus far…