In the Archives: A Coldwater Doll

Editor’s note: Laura Bien’s look back into the archives this time around is not really about trains. But there’s a public transit titbit that will likely stand out for readers who’ve been following The Chronicle’s coverage of the Ann Arbor Transportation Authority’s effort over the last year to develop a transit master plan for Washtenaw County.

Thirteen-year-old Ida ran upstairs into the bedroom and opened the closet. Such beautiful things – skirts, dresses and blouses – which one to pick? She selected a long brown skirt of light, glossy brillantine and a brown wool shirt stitched in red silk. They would look lovely with Ida’s brown hair. The clothes were too large, but so much nicer than the drab blouse, faded blue skirt and worn, over-the-ankle black shoes she had on.

Coldwater Public School as it appeared at its opening in 1874, with the administration building in the foreground and children's cottages in the rear.

There wasn’t much time – she quickly changed.

“Ida!” called a woman from downstairs. “Suppertime!”

It was the eve of Halloween in 1905, but Ida wasn’t selecting a costume, or playing dress-up before Saturday dinner. She was planning an escape.

And although she lived with Mr. and Mrs. Curson* in Ypsilanti’s prosperous Normal Park, she wasn’t their daughter, or even a relative. Ida’s relatives had abandoned her.

That night, her place at the table remained empty.

Local newspapers in Ypsilanti and Ann Arbor later pieced together the story. Ida walked downtown and took the 5:45 interurban to Ann Arbor. She went to Mack’s, a large department store on South Main Street, and bought a fancy collar and an elaborate hat. Then Ida traveled to Detroit and checked herself into a hotel near the downtown Campus Martius area. She used $10 [about $240 today] she’d taken from the Curson home.

The next day, Ida went shopping in Detroit. She bought a plain, unclothed doll, a fancy shawl for it, and a length of silk intended for doll clothes. For herself, she bought three hair combs, a pair of gloves, and some ribbons. Sunday night she checked back into the hotel.

On Monday evening, local papers later said, Ida started back to Ann Arbor where she’d seen a help-wanted sign. She got as far as Ypsi before tiring out at 10 p.m. Disembarking at Ypsi, she was recognized by interurban agents.

Ida was hard to overlook. Not only were her fancy clothes (sized for a grown woman) ill-fitting for a 13-year-old girl, she wore them strangely. Her blouse flopped loosely outside her skirt instead of being neatly tucked in according to the custom of the day. Her new collar looked incongruous and her elaborate hat was suitable for a 50-year-old society matron.

“[T]he manner of donning the dress was, if modish, decidedly new to Ypsilanti,” joked the October 31 Ypsilanti Daily Press, calling it “recherché.”

There was a reason, unexplored by the newspaper stories, why Ida wanted beautiful things – and why she had no idea of how to wear them. She was a Coldwater girl.

Located in Branch County’s town of Coldwater, Coldwater State Public School was Michigan’s institution for abandoned or resourceless children. Established in 1871 by a legislative act and opened in 1874, the school took in children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Some were children living in – and sometimes born in – county poorhouses. Some had mental deficiencies or behavior disorders that some families, given the scant resources of the day, found too difficult to handle, or else thought that the public school could better address to help their child. Officials had taken some children from families judged unfit. And some, like Ida, were those whose foster placement with relatives had failed – Ida’s aunt and uncle had sent her to the school.

When she arrived, the school consisted of 160 acres with an elegant Second Empire administration building, nine “cottages” for the children, a school, chapel and dining room, hospital, and working farm.

Coldwater wasn’t meant to be residential. It allowed children to be adopted out, or contracted out under a work indenture plan with both the school and the child receiving payment. The school’s agents, one for each Michigan county, logged much time on the train assessing the homes of those who’d requested a child, checking up on previously placed children, and transporting children from bad situations to Coldwater.

By the time Ida arrived at Coldwater around 1904, 5,790 children had been received at the school since its opening, according to Reverend Henry Collins’ 1906 history of Branch County. Of these children, 1,207 were indentured out, 687 were legally adopted, 589 were restored to their parents, 749 were returned to their home counties, 360 aged out, 186 married, 172 remained in Coldwater, and 1,613 became self-supporting. Roughly one in 25 – a total of 227 – had died, either at the school or at the host home.

“While the maintenance of children in orphan asylums costs other states from fifty to one hundred dollars per year for each child,” Collins wrote, “the large number who are successfully indentured into good homes by the ‘Michigan plan’ as it is generally known, has reduced the average expense to the state per child from year to year to less than twenty-eight dollars, and the ‘Michigan plan’ places children in that best of all places for their successful growth to the ideal manhood and womanhood, the homes of its people.”

Those who didn’t share Collins’ roseate view of “placing-out” included Coldwater’s superintendant from 1875 to 1883, Lyman Alden. In 1885 he read a paper at the National Conference of Charities and Corrections titled, “The Shady Side of the Placing-Out System.”

Lyman was an idealist, and judging from his writings, he both hoped for and worked to create the best possible conditions for Coldwater children. In one annual report to the state legislature, he indirectly criticized that body for failing to provide toys. “While no provision has yet been made by the Legislature for the purchase of playthings, such as croquet sets, carts, balls, etc., etc., still the children have managed to extract considerable fun out of pretty scanty material … a base ball club has been organized.”

Lyman was also a realist, with a clear-eyed view of the deficits of “placing out” and the integrity to be blunt about it. He began his conference paper, “It is well known by all who have had charge of the binding out of children that the great majority of those who apply for children over nine years old are looking for cheap help.” Lyman went on to quote no fewer than seven prominent child welfare officials who agreed.

“Now, all this does not prove, nor is it intended to prove, that many good homes cannot be found for children, if proper care is taken,” Lyman continued. “I know that thousands of such homes have been found, where the children are treated with affectionate consideration.”

Many families found a Coldwater child to love and raise to a successful adulthood, as they weathered the normal worries and trials of parenthood along the way.

Ida, captured and in Ypsilanti police custody, wasn’t as lucky.

The police consulted with the Cursons and with Coldwater’s Washtenaw County agent, Mr. Childs. A decision was made.

Ida returned to Coldwater. It’s doubtful she was allowed to keep her doll.

Ida would remain at Coldwater until she was at least 18, two years beyond the school’s original age limit of 16. At that time, she was one of 172 wards, 46 of whom, like Ida, could read and write.

In 1910, Ida was the oldest ward at Coldwater.

One hopes that the apparent absence of records for Ida after age 18 is explained by her “growth to ideal womanhood” of the day: She left the school, married, and changed her name. There’s at least a good chance that the resourceful gumption of the 13-year-old who successfully navigated around Detroit on her own for a few days helped Ida succeed in later years.

One also hopes that Ida enjoyed a happy adulthood, with enough money to now and then buy some beautiful thing of her own that no one would take away.

*Name changed due to living descendant.

Mystery Artifact

Last column, Imagine and cmadler correctly guessed the Mystery Artifact: a gaiter, or, protective covering for the lower leg and upper shoe.

They’re still around. Imagine noted, “We still use gaiters today, but they look somewhat less form fitting, and are used to keep snow or scree out of your boots. Mine are for x-country skiing and keep the snow out. They’re made of gore-tex… instead of buttons, mine come with velcro fastenings.”

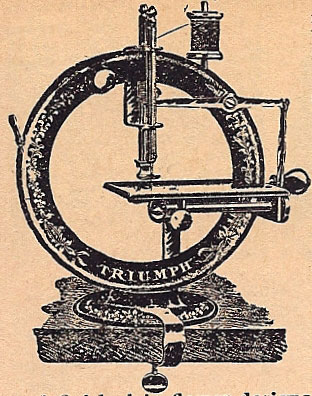

This time we’re faced with a weird circular object. Hint: It’s something that likely Ida never owned. What is this odd device?

Take your best guess and good luck!

Purely a plug: The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our columnists and other contributors. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

That’s a toy sewing machine. My father was in the industrial sewing machine business. They used to keep a few of these around the office for decorative purposes.

Here’s a photo of one: [link]

Described as follows: [link]

Round Wooden Triumph Sewing Machine

This scarce sewing machines features one of the most unusual and graphic designs that was ever thought up! It is believed to have been manufactured by the Foley & Williams Co. and is simply marked “Patent Appld For”. The unusual round body is all wood with a metal backing plate, and the body was designed with a small section of frame that could be removed while sewing to allow the fabric to pass through, then replaced when not in use to keep it stable. These machines are seldom found and rarely offered for sale, and because of their age, design and material they are generally found incomplete and in worn condition. This example is 100% complete with all of it’s original parts, including the removable section and its retaining pin. You will be proud to display this example along with your other “top-shelf” small sewing machines.

Good + ….. $1650.00 SOLD

That’s an interesting suggestion, Judy. I did wonder if Ida learned to sew at Coldwater (as she bought a piece of fabric for doll clothes, not a finished doll garment); they did have sewing classes there.

cmadler: Six-bleepin’-teen HUNDRED DOLLARS for a toy sewing machine?! Good gracious! Though now that I think of it, I did read somewhere that salesmen’s mini demo models of sewing machines fetch a good price on the antiques market.

It sold for just over $1 in the early 1900s, which was lot for toy. If she did learn to sew at Coldwater, it would have been by hand or on a real machine, not this toy.

Inflation calculator says $1 in 1904 would equal around $24 today. I agree, she would have learned hand-sewing. Some of the descriptions of the academic classes are fairly heartbreaking. You have to read between the lines but it’s suggested that they were dealing with a huge range of special needs that no one really knew how to deal with according to modern practices.

However it’s a little-known fact that treatments for special needs children/adults were actually quite homelike and humane in the mid-19th century, and actually grew less individualized in the first half of the 20th century. An excellent book on the subject is “Inventing the Feeble Mind: A History of Mental Retardation in the United States” by James W. Trent.

This book is fascinating, for me primarily because in reading about how American society and culture reacted to this cohort of people over time one gains insight about changing attitudes towards marginalized populations. It’s very informative on a number of levels.