In the Archives: Huckleberries and Trains

Editor’s note: As discussion of major investments in commuter rail service continues in the Ann Arbor region, Laura Bien’s local history column this week takes a look back to efforts more than a century ago to establish rail connections in the region. Does southeastern Michigan have the wherewithal to enhance existing connections and establish new ones? Or is all that just a huckleberry above our persimmon?

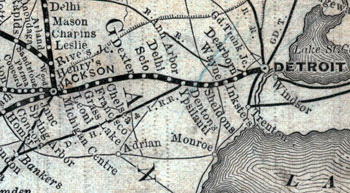

This 1895 plat map shows the Huckleberry curving from northern Ypsilanti towards Washtenaw Avenue. (Images link to higher resolution files.)

By the 1980s, the century-old train tracks had been torn up. Now occupying the former roadbed are new Eastern Michgan University buildings, the Washtenaw Avenue Kmart, the abandoned Carpenter Road mini-golf park just south of Thrifty Florist, and Pittsfield Township homes. But only a few years earlier, a sleepy southbound rail line with only one slow train rumbling by a day, was an ideal route for rural nature walks, south of the rail crossing on Washtenaw just east of Golfside.

Onetime Ypsilanti Press linotyper and history columnist Milton Barnes remembered. Barnes was blind. Yet in an early-1980s column for the Press, he helped others visualize a summer ramble.

“Strolling-just a-strolling, down these tracks in late August,” Barnes wrote, “we found a bed of wild strawberries, just a few of them, but as sweet as can be. The spring crop of polliwogs had grown into lively green frogs. There was a bit of water in the ditches along the tracks, with buttercups and cowslips … When we stroll along, and hop from tie to tie, every cow, lamb, dog, pig, and rooster watches. So do the farmers from their back doors, and some wave a cheery ‘How be ye?’ greeting.”

A century earlier, the July 4th inaugural voyage of the slow little “Detroit, Hillsdale, and Indiana” steam train from Ypsilanti to Saline and beyond was cause for citywide celebration.

The Huckleberry Line, seen here as the diagonal line between Ypsilanti and Bankers, Michigan, also stopped at Pittsfield Junction, Saline, Bridgewater, Manchester, Watkins, Brooklyn, and a few other stops before its terminus 64 miles southwest of Ypsi.

“[F]rom 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. a constant stream poured to the [Ypsilanti] Depot,” reported the July 9, 1870 Ypsilanti Commercial. “The first train carried 600 of our citizens … [t]he morning was lovely, a gentle breeze; the train went just fast enough to enable the excursionists to enjoy the ride. The Ypsilanti Tin Horn Band enlivened the occasion.”

It’s likely that more than one farmer south of Washtenaw Avenue looked up from chores at the sound of distant metallic tootling to see the small traincars creeping over the horizon, on their leisurely way to Saline.

“Arriv[ing] at Saline we found thousands waiting to welcome us,” the Commercial continued. “A beautiful arch erected over the track … was wreathed in flowers [spelling out] ‘Saline’ and ‘Ypsilanti’ clasping hands and the word ‘Welcome’.”

The attendees listened to a welcoming address, gave three cheers, enjoyed the Saline Cornet Band “discoursing soul inspiring music,” and proceeded to Risdon’s Grove for a lavish banquet under the trees, followed by ceremonial orations.

The “D. H. & I” was not the first rail line to visit either Ypsi or Saline.

The Michigan Central arrived in Ypsi in 1838, and the Michigan Southern arrived in Saline in 1843. But a rail line uniting then-remote agricultural Saline to the nearby urban markets of Ypsi and Ann Arbor was a boon to farmers. The line’s name changed in a series of buyouts. – first to the Detroit, Hillsdale, and Ypsilanti line then the Detroit, Hillsdale, and Southwestern. Finally, it became a minor branch of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern network.

The Ypsilanti Commercial’s fiery editor C. R. Pattison had led the fight (at least in his view) to secure the Ypsilanti-Hillsdale County railroad. Throughout late 1869 and early 1870, the Commercial published a series of editorials boosting the merits of the proposed line, in an era of feverish and competitive railroad-building.

Officials in Detroit and Ypsi conferred and decided to donate municipal funds. “Hillsdale subscribed $100,000 [1.7 million dollars today], Ypsilanti voted $50,000, and all the villages and townships on the proposed route voted or subscribed large sums of money,” wrote Charles Chapman in his 1881 History of Washtenaw County.

The state took note, and objected that this wasn’t a legal way to raise money for a railroad, according to the Michigan constitution. Through a series of twists and turns that included a case going to the U.S. Supreme Court, the matter was finally settled and the track began to be laid, via rights-of-way on farmland ceded by local farmers between Ypsi and Saline.

The farmers weren’t just being altruistic. Having a nearby rail line meant an easy way to quickly ship goods to market. The Hillsdale line was the single most important factor in boosting Saline into a then-primary hub of agricultural exports to southeastern Michigan. The Saline depot hummed with commerce, as livestock, logs, finished lumber, apples, wheat flour, ironwork, and wool from local sheep farmers were loaded onto cars and shipped out.

The line carried passengers, too. One was a family member of Superior Township Scottish immigrant farmer-poet William Lambie. In August of 1875, he noted in his diary, “Found a swarm of bees on the trunk of a small hickory tree-brushed them down to the hive and they stung fiercely. Went to the Depot with Bell. She and Willie Campbell started for Brooklyn on the Huckleberry [as the line was nicknamed].”

One favorite destination on the line was Watkins Lake, halfway to Hillsdale. One turn-of-the-century diarist, quoted by Milton Barnes in another column about the Huckleberry, detailed an end-of-school outing for 1894 Normal School [EMU] graduates.

“[T]hey started late because the class president and his partner had a hard time carrying a basket of lunch across the fields of the [Ypsi] depot.” The article went on to say that the dean of women checked each girls’ attire to make sure it was suitably modest and kept a sharp eye on the grads as they journeyed south to Watkins’ Lake. Canoes were rented and some grads wandered off hand-in-hand, the article said, to gather wild strawberries. “At the picnic tables there wasn’t enough potato salad and some of the chicken and cheese sandwiches were made by girls who got low marks in domestic science.” The canoe rides made up for that, and the happily worn-out group returned to Ypsi at sunset.

After the turn of the century, automobiles slowly grew in popularity – in 1913, one in 47 Washtenaw residents had one – and farming began to decline. The old Huckleberry Line to Saline carried less freight and fewer passengers, and the frequency of trains was cut back. A January 17, 1908 Ypsilanti Daily Press article reported, “The most serious change in the new schedule is the cancelling of two passenger trains on the Lake Shore. These are the morning train from Hillsdale which ran through to Detroit [borrowing the Michigan Central track for the run between Ypsi and Detroit], and the afternoon train from Detroit to Hillsdale. In place of this fine service a passenger coach will be attached to the local freight from Hillsdale. Its arrival and departure are more uncertain than April weather.”

By 1923, Harvey Colburn nearly mocked the residual rail line in his “Story of Ypsilanti.” “The magnificent dreams of the original promoters have vanished,” he wrote. “Today, more than fifty years after the incorporation of the road, two plug trains a day … each train composed of a short string of freight cars with an ancient passenger coach on the end, pull out of [the Ypsi depot] and gently amble down the Huckleberry Line.”

Passenger service was discontinued in the 1930s, and freight service stopped in 1961. In an era of car ownership, the old Huckleberry Line was obsolete, its tracks soon scrapped – but not its memory. Around 1972 the Huckleberry Party Store opened for business near the onetime railroad spurs that used to cross Washtenaw just east of Golfside.

In a simpler time, the tracks were nearly the stuff of poetry.

“Sometimes on our strolls,” wrote Milton Barnes, “a farmer would lean over his fence and want to talk. He would tell us just where along the tracks in June would be found the best patches of wild strawberries … [h]e would also tell us that the roots of the cattails which grew in the trackside ditches were good to eat, somewhat like a sweet onion …”

The railroad’s countrified nickname came about as it was said the train was so slow (around 20 miles per hour, according to railroad surveys) that a passenger could hop off at one of its many stops and pick huckleberries – or, as Barnes and the Saline Historical Society claim, strawberries.

Today part of the onetime line is the paved east-west bicycle path – part of the county’s Border to Border trail – between EMU’s Rynearson Stadium and Collegewood Drive. The shady forest path links the campus with Hewitt Road and the Convocation Center. About halfway down the path at an undisclosed location stands a giant thicket of blackberries – currently in season. It may be that some nostalgic bicyclist recently retraced this section of the Huckleberry Line and, hopping off the imagined train, stood in the sun, gazed down the “track,” and gorged on berries like the riders of long ago.

Thanks to Preservation Eastern director Deirdre Fortino and Saline Historical Society member Robert Lane for research assistance.

Mystery Artifact

Russ Miller and Cosmonicon correctly guessed last column’s Mystery Artifact. It’s the stump of a tree turned into a mortar for pounding corn into corn meal. “Ordinary conveniences were few in the settlement [of Woodruff's Grove]” writes Harvey Colburn in “The Story of Ypsilanti,” “and most of what was needed had to be made on the spot.

There was one oven, that constructed by Woodruff, in his yard, built of stone plastered over with mud. A staple food was corn … [w]ith the demand for meal, two mills were fashioned by burning holes in the tops of sound oak stumps, and scraping them smooth and clean. Over these makeshift mortars hung pestles suspended from a spring pole … the noise of their thumping was heard every winter morning.”

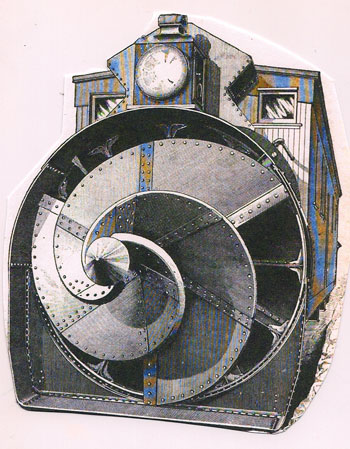

This time we’re faced with a rather scary Mystery Artifact.

Now, I cheated a bit in trimming away the explanatory text around this object that gives it away. But what is it? Good luck!

Purely a plug: The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our columnists like Laura Bien and other contributors. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

That’s easy, it’s a rotary snowplow for use on a railroad. I’m guessing you don’t actually have one and this is just a drawing.

Jim: Well, taking a look around here and some of the beloved old bits of junk all over the house….you never know!

First I thought it was for confusing buffalo, but then I was this: [link]. Jim’s right—I want one on my street too.

Oops, “I saw”—the perils of dyslexia.

Cosmonican, wow, what power! One comment said 2500 horsepower. I could watch that all day, what a monster! I too would love to see some of these (truck version) parked in our DPW yard. Terminating urban snow in the most violent and dangerous manner possible…….would actually be pretty cool. Thank you for the video link.

Cute idea, but nope. It is designed to look sort of like a rotary snowplow, but even that is not well done – I’ve been a RR fan for years & know what the front looks like. My guess for the Mystery Artifact is a meat grinder! Ground meat is expelled through the front.

Well, that’s my guess anyway.

Larry: It does look as if it could process a wayward cow in no time, you are right. :)

I agree with Jim. It is a snowplow.

Irene Hieber

Modern ones have vanes rather than a screw. I was assuming this was an older model. And I can’t think of anything else it could be.