In the Archives: Purebred Michigan

Editor’s note: Laura Bien’s In the Archives column for The Chronicle appears monthly. Look for it around the end of every month or towards the beginning, if things slide a bit – like this month.

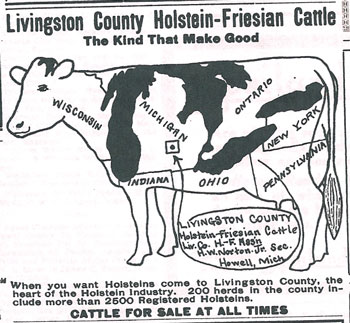

A 1914 ad for the Livingston County Holstein-Friesian Association shows a cow with familiar markings.

Ypsilanti has never lacked for beauties, as any conductor on the onetime Packard Road interurban could have told you. Hordes of University of Michigan boys crowded the streetcars on weekends en route to their belles at Ypsilanti’s Normal teacher training school (which became Eastern Michigan University).

On the way, the young men unknowingly passed the home, at Packard and Golfside, of another belle more famous than any Normal girl. She was quiet and stocky, yet viewed as beautiful.

She had numerous relatives at the insane asylum at Pontiac, which in her case was regarded as a prestigious lineage. Thousands statewide knew her name. Many owned her children.

Pontiac De Nijlander was the state’s epitome of cow excellence in an era characterized, in the agricultural sphere, by what could be called Michigan’s turn-of-the-century “Holstein fever.”

A typical big-bodied black-and-white-splotched Holstein, Pontiac De Nijlander lived at Ypsiland. The 180-acre farm extended from Packard to Ellsworth, bordered on its east side by Golfside Road and owned by brothers Norris and Herbert Cole. Norris eventually bought his brother’s share and became sole proprietor of the farm, whose principal business was breeding top-quality Holstein bulls and cows.

Of Dutch origin, the breed had established its supremacy at an 1887 “battle of the breeds” in New York’s Madison Square Garden. Four hundred cows from the four top dairy breeds – Guernsey, Jersey, Ayrshire, and Holstein –competed to see which breed was the best producer of milk and butter.

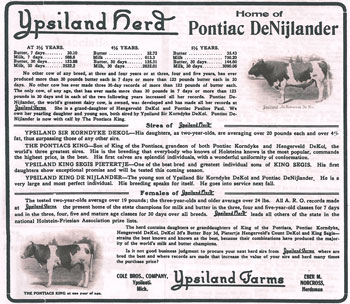

Ypsiland Farms proudly declared itself as "home of Pontiac De Nijlander" in this wordy 1914 ad from the Michigan Dairy Farmer."

The Jersey Cattle Club was confident that their breed would win the butter contest. They commissioned an elegant silver cup for the winner, engraved with the image of a stately Jersey cow. In a surprise upset, the cup was won by Clothilde, a now-legendary Holstein. Today the Jersey cup resides in the Holstein Association USA headquarters in Brattleboro, Vermont.

“Previous to this public test and victory,” wrote Frederick Houghton in an 1911 edition of the Holstein-Friesian Register, “whenever the Holsteins were spoken of as butter cows a sarcastic smile would illuminate the faces of the breeders of what had been termed the butter breeds. Not so now.”

The large, high-yielding breed spread to Michigan and breeders’ clubs formed on the county, regional, and state level. Before purebred breeds arrived in the state, most farms had a few head of “grade,” or ordinary, non-purebred cattle. High yields convinced many to switch to purebred, registered Holsteins.

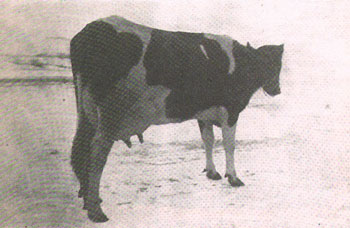

A photo from the 1914 Holstein-Friesian Register highlights the business end of the famed 35-pound Ypsilanti cow, Pontiac De Nijlander.

Michigan breeders sought cows from the most prestigious Holstein family lines, such as the Clothilde line. That line began with the silver-cup-winning cow, who had been imported from the Netherlands in 1880.

The Aaggie line originated from a Dutch cow imported in 1879. The De Kol line began with another Dutch cow imported in 1885. Other famous lines included the Glista, Johanna, Korndyke, Netherland, Pauline Paul, Pietertje, and Segis.

A cow’s or bull’s name generally reflected (and still reflects, with modern-day breeders) her or his birth-farm and maternal and paternal lineage. One bull named Ypsiland Korndyke De Kol Pietertje – born at Ypsiland around 1907 and later sold to a Howell dairyman – likely had the blood of the Korndyke, De Kol, and Pietertje lines.

Somewhat arcane, the art of cattle nomenclature occasionally stumped even cattlemen, as illustrated in a vignette from the May 15, 1915 edition of Brownell’s Dairy Farmer magazine, formerly The Michigan Dairy Farmer:

A group of the “old guard,” at the recent Howell sale, were discussing the names of various Holstein sires, among which was that of the sire owned by a prominent Livingston County breeder. The last word of the name of this sire is “Mobel.” All doubt as to the origin of this word was set aside by H. W. Norton, Jr. “The word ‘Mobel,’” he said, ‘is spelled in that manner because it is the masculine of ‘Mabel.’”

“Well, I never knew that before,” said a young breeder, as the veterans made frantic efforts to keep their faces straight.

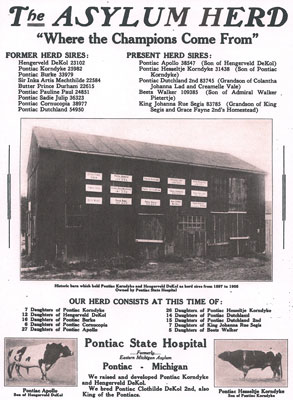

Michigan had its own prominent Holstein lines developed within the state. One of the best was the Pontiac line, bred at the Pontiac State Hospital, formerly called the Eastern Michigan Asylum for the Insane.

This full-page ad for the Pontiac State Hospital herd shows a barn decorated with the nameplates of past champion cattle. At lower left is Pontiac De Nijlander's father, Pontiac Apollo. From the August 1, 1914 Michigan Dairy Farmer.

At the time, many Michigan state and county institutions owned registered Holstein herds. The milk was welcome and breeding programs were profitable: the Pontiac asylum’s initial purchase of cattle worth $1,500 increased in value to $60,000 eighteen years later [about $1.5 million today].

Branch County’s Coldwater State Public School for Needy and Dependent Children had a herd that included the registered bull Commodore Pietertje De Kol Aakrum. The herd supplied all of the daily milk needed for the staff and 270 or so children. Wayne County’s poorhouse and asylum, Eloise, developed a purebred herd of 107 animals. The Traverse City State Hospital’s cow Traverse Colantha Walker broke milk-producing records in her lifetime. The Michigan Farm Colony for Epileptics in Tuscola County, the Michigan Home and Training School in Lapeer County, the state reform school in Ionia County, and the Michigan School for the Deaf in Flint all maintained good-quality Holstein herds.

Cows and bulls from the Pontiac line were sold at high prices to breeders around the state. One bull purchased by the Cole brothers in Ypsilanti, The Pontiacs King, became one of several sires of Ypsiland’s herd. Investing in good-quality animals paid off; by 1915, Ypsiland had bred and sold 36 bulls to cattlemen in Bay City, Lansing, Battle Creek, Grand Rapids, Howell, and other Michigan locations.

Ypsiland owner Norris Cole had stature in the local Holstein community. When the Washtenaw Holstein Association formed in December of 1915, he was elected to an office, as noted in an account of the group’s inaugural meeting in the January 1, 1916 edition of Brownell’s Dairy Farmer:

The election of officers was next to order. [Veteran Willis breeder] Harvey S. Day was urged to become president but firmly refused. William B. Hatch was proposed, [but refused]. Norris A. Cole was also nominated. He attempted to decline, but the breeders were becoming tired of this custom and Mr. Cole was forced to take the office . . . Harvey S. Day was nominated and elected vice president before he could rise to his feet to decline.

Part of Norris’ local eminence at the meeting was due to one of his cows who had recently smashed a state record for butter production. Born on March 10, 1908 at the Pontiac asylum and purchased by the Cole brothers a year later, Pontiac De Nijlander was the daughter of Pontiac Apollo and the granddaughter of the legendary bull Hengerveld De Kol.

A standard measure of the day was the “7-day test,” a week during which a given cow’s output was measured. Pontiac De Nijlander outstripped all other Michigan cows by producing 35.43 pounds of butter, a number that Norris immediately featured in his ongoing Brownell’s Dairy Farmer advertisements for Ypsiland. Until that point, a 30-pound cow had been considered exceptional.

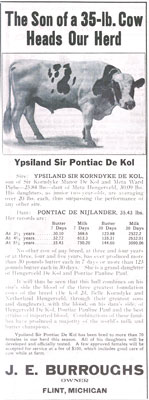

Breeders who bought cattle related to Pontiac De Nijlander often proudly advertised their stock. This is her son, who was purchased by Flint breeder J. E. Burroughs.

Other breeders took note and were quick to point out their own cattle’s relationship to Pontiac De Nijlander in their advertisements in 1914 editions of Brownell’s Dairy Farmer. Bay City breeder W. A. Wilder extolled his heifers who were bred to a bull whose aunt was Pontiac De Nijlander. Redford breeder Martin McLaulin pointed out that his cow Pontiac Hazel was an aunt of Pontiac De Nijlander. Flint breeder J. E. Burroughs said that the famed Ypsiland cow was the mother of his herd’s sire. Perry breeder C. R. Wilkinson stated that his bull had Pontiac De Nijlander as a grandmother. Azalia breeder Fred Bachman said that the mother of his prize bull was a “3/4 sister to the great cow, Pontiac De Nijlander.”

Pontiac De Nijlander’s achievements were eclipsed over time as dairy cattle breeding continued to improve. During the Depression, individual cows were producing an annual average of 4,379 pounds of milk, a figure that climbed to 5,512 by 1955, 8,080 by 1965, 10,360 by 1975, and 18,204 by the year 2000.

One recent champion, Wisconsin’s Ever Green View My 1326 ET, produced 72,120 pounds of milk in a year, or 23 gallons per day, aided by bovine growth hormone.

Over time the profile of dairy farms changed as well. In 1940, the nation’s 4.6 million dairy farms (farms that just happened to have a cow or two were included) had an average herd size of 5 cows. By 1970, the nation’s 647,860 dairy farms each held roughly 19 cows. By 1990, 192,000 farms each held an average of 55 cows, climbing to 88 in 2000. Today at large dairies, the number is often several hundred, even thousand, head of cattle. Holsteins are by far the dominant breed in modern American dairy farming, with Michigan the nation’s eighth largest dairy producer.

A subdivision now occupies the site where Pontiac De Nijlander once nibbled grass alongside Golfside Road. Though she is long gone, her DNA lives on in modern Holsteins. And the “Pontiac” line name still occasionally surfaces in the names of prize-winning Holsteins.

From asylum to accolades, one Ypsilanti cow broke the records of her day and won fame for Washtenaw County.

Mystery Artifact

Last month’s Mystery Artifact related directly to the story of Michigan sturgeon. As cmadler guessed, it is a “pound net,” once widely used on the Great Lakes.

Pound nets were set with the long straight section pointing perpendicularly towards shore. Fish swimming parallel to the shoreline encountered the barrier and instinctively turned and swam along it, which led them to the nested chambers of the pound net, leading to the final small compartment. Fisherman simply hauled up and emptied this fish-filled compartment into their boats.

This time we return to land in order to examine this strange artifact. What might this object be? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and “Hidden History of Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our columnists like Laura Bien and other contributors. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

It looks like a spray can, maybe for pesticide application? Although given the theme of the column, perhaps I should be speculating along the lines of milk collection…

It’s a blow torch, as anyone who grew up watching the Three Stooges can tell you.

TJ: Interestingly enough, they had automatic milkers before rural electrification. I saw several in the old dairy magazines I was reading. They operated not unlike a manual bicycle pump. The part that hooks on to the udder looked similar to modern machine milkers, and a hose from those fed into a central can. It could milk two cows at once, which must have been an amazing labor-saver in 1914.

Jim: The Three Stooges started as a live vaudeville act as you know…and they were still making films into the 1950s, amazing.

What a lovely article! I want a cow now! :)

Can you believe they are making the Three Stooges into a movie?! Ugh!

This sent me to the Calder Dairy website [link] where I ascertained that they have a number of Jersey cows as well as Holstein and Brown Swiss. (Their trucks are sometimes painted Holstein.)

The phrase, “aided by bovine growth hormone” gave me the shudders. The reasons so many of us seek out milk not produced by this assist are well known (it leads to overuse of antibiotics) but it has also been responsible for the bust in the dairy industry. As with all other agricultural commodities, dairy farmers do better when they have a good production year as everyone else is failing. Overproduction ruins the market. We’ve had perennial crises in milk prices, milk being poured on the ground, subsidies voted in to support a local industry, the works, partly because of this practice.

(Calder doesn’t use it.)

My daughter & son-in-law (Becky & Bryan Welch) believe it is an acetylene torch.

It is a blowtorch. And it is a very dangerous tool! Gasoline is used as the fuel and the bottom tank is partially filled with it. Then, using the pump (the handle is the thin horizontal one on the left), the tank is pressurized. In order for the torch to work, the combustion head has to be hot to vaporize the incoming fuel. To get the torch started initially, a small amount of gasoline is allowed to fill the shallow tray (visible immediately below the head) and set afire with a match. As it burns, it heats the head. When the head is deemed hot enough, the main valve is opened (circular handle on top) and a vaporized fuel shoots out of the end which is then ignited with a match. The flame spreads back into the head to ignite the incoming fuel and to keep the head hot. The end result is a short but broad working flame unlike that from an acetylene or propane torch. Because of the need to keep the head hot, once started the torch is left running continuously for the duration of the job. If the head is not hot enough, instead of vapor you get a stream of gasoline which may be burning – i.e. a flame thrower! As you can see, there are many opportunities for some serious accidents here.