In the Archives: On Keeping Your Pants Up

Offered at Ypsilanti clothing store Sullivan and Cook almost exactly 100 years ago – in July of 1912 – were invisible suspenders.

On absorbing this tidbit of information, the perplexed reader may justly wonder how on earth one could pick out a particular style of said accessory – or would style even matter? At a 2-for-1 invisible suspender sale, how would a buyer know he’d received both pairs? What if the invisible suspenders were mislaid around the house, never to be found again?

Such questions are justified, if slightly surreal, for anyone unacquainted with this clothing item once widely available in Ypsilanti, Ann Arbor, and across the nation.

From obscure elastic hangs a tale of changing worlds.

Far from being a passing fad, invisible suspenders were a tiny signifier of vast inexorable social change in early 20th century America, and as iconic in their humble way as the Model T.

Early Suspender History

The history of suspenders in America begins with the heddle loom. This tabletop or small standing loom could produce a range of fabric strips, bands, decorative trim, and suspenders. Early suspenders were also sometimes knitted.

Suspenders next became an urban tenement industry. In his 1853 book “Life in New York, In Doors and Out of Doors,” William Burns offered an unblinking look at the ill-paid work of tenement women almost four decades before photographer Jacob Riis’ sensational tenement expose “How the Other Half Lives.” James’ book contains an illustration and essay for each of 40 low-wage female occupations that include wool-picker, fancy box-maker, gimp-weaver, straw-braider, and suspender-maker.

The suspender business, said the book, was “a first-rate business for the dealers – for the employees, the workers, we suppose it pays starvation wages, little more.” The suspender-maker’s father had lost his fortune and hanged himself, leaving his daughter an orphan. “She was quite a belle when her father was rich,” continued the essay, “and was beset by numerous suitors. They don’t know her now …[and couldn’t] recognize her now with a double-barreled opera glass.”

The suspender-maker brought her finished goods to the dealer each day and picked up new material to bring back to her room, perhaps buying a little bread or other cheap food along the way for a meager meal. There was no Sunday, vacation, pension, insurance, or eight-hour workday for her — it was work or starve.

The suspenders she and her colleagues made were shipped across the nation. Suspenders (also called braces) were a ubiquitous 19th-century clothing item for everyone from farmers to industrialists. In front, each of the two straps ended in a V-shaped leather “frog,” each end of which had a buttonhole for attaching to exterior pants buttons. In back, the straps combined into a Y-shape and ended in one frog, or crisscrossed in an X-shape, ending in two frogs. Suspender clamps didn’t appear until late in the 19th century. Most 19th-century pants had a waist well above the navel, making them unsuitable for belts.

Divergence of Suspender Opinion

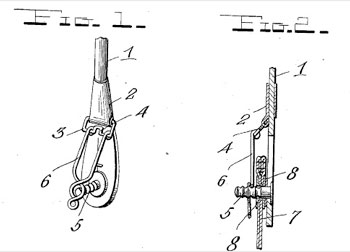

Suspenders were uncomfortable. They trapped the shirt against the body in hot weather and restricted movement. The degree to which suspenders dissatisfied wearers may have some relation to the era’s vast number of suspender-related patents. In Michigan alone, nearly 30 such patents were filed between 1888 and 1922, including Ypsilanti carpet weaver George Hubbard’s 1911 patent for a “Garment Supporter” clamp. People couldn’t stop tinkering with their braces.

Opinions were divided. “Even the light pressure of suspenders tends to make the shoulders round and the chest contracted,” wrote Alfred Woodhull in his 1906 book “Personal Hygiene Designed for Undergraduates.” “[With] normal hips the trousers should be sustained by a broad, moderately tight belt above those bones.”

John Harvey Kellogg expressed the opposite opinion in his 644-page 1888 opus “Plain Facts for Young and Old.” “The dress must be so adjusted to the body that every organ will be allowed free movement. No corset, band, belt, or other means of constriction should impede the circulation. Garments should be suspended from the shoulders … by proper suspenders.”

An ongoing demographic trend in the state influenced the clothing item. Social patterns were changing fast in the last half of 19th century Michigan. In 1850, 93% of Michigan residents lived on farms and 7% lived in cities. Michigan steadily urbanized; the urban population rose to 13 per cent in 1860, 25 per cent in 1880, 40 per cent in 1900, and 61 per cent by 1920. Ann Arbor’s population increased from 5,097 in 1860 to 19,516 in 1920, with Ypsilanti’s similarly jumping from 3,955 to 7,413. Both cities developed and prided themselves on municipal improvements: telephone and electric service and water and sewer systems.

Cityfolk could push a button for electric light, flip a switch to turn on a gas stove, and turn a tap to get unlimited indoor water. Rural electrification wouldn’t come to non-urban Washtenaw County until decades later. Meanwhile farmwomen lighted kerosene lamps, tended coal- or wood-fired stoves, went to the outhouse, and poured hot water over the frozen outdoor water pump in winter to try and thaw it.

Rural folk without a convenient way to visit town had one resource – the Sears, Roebuck catalog. Among its turn-of-the-century offerings were cheap ready-made clothing, distinguished by “stove-pipe legs and soap box waist line in the trousers … The man of that day with a belt on was a rarity, and as for supporting his trousers with them he could not do it without looking like [a] sewing bag drawn taut in the middle. Suspenders were imperative!” So said the December 21, 1911 issue of the advertising trade magazine Printer’s Ink. The 1903 Sears, Roebuck catalog offers a mere 12 belts but boasts an entire “Suspenders Department” with nearly 30 choices.

Towards Belts

Nevertheless, “[s]uspenders are rapidly going out of fashion – especially among young men and good dressers,” said the same issue of Printer’s Ink. The good dressers could afford the more tailored, slimmed-down men’s clothing coming into vogue around 1910. Utilitarian braces holding up ready-made trousers were fine for a farmer, but a modern city’s shopkeeper, as one example, was expected to have a more polished appearance with a suit or at least a vest covering his braces.

For those who wished to forswear a vest in a hot un-air-conditioned store, a belt became imperative for summer. “It is a time when every man whose physical conformation allows of it is preparing to cast aside his suspenders for the summer and adopt the belt,” noted an early summer 1909 issue of the trade magazine The American Tailor and Cutter. “The belt most endorsed for summer measures about an inch and is made of pigskin or Russian leather,” said the July issue of the Businessman’s Magazine and the Book-Keeper.

Invisible Suspenders

The belt, however, was uncomfortable for those with a generous girth. A solution came along in 1900 when Chicagoan Edward S. Halsey invented invisible suspenders.

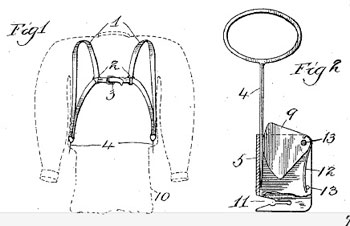

The suspenders, nearly identical to regular fabric suspenders, were worn over a man’s undershirt but under the outer shirt, attaching to buttons sewn in the pants’ interior waistband. “The object of my invention,” wrote Halsey in his patent application, “is to supply a means of supporting a man’s trousers from the shoulder … so as to relieve all strain and distortion from the shirt, also relief from the hips, and giv[e] the wearer greater comfort and a neat and tidy appearance when wearing an outer shirt without coat or vest.”

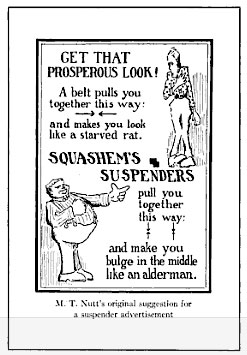

Around 1920, The Suspender Manufacturer’s Advertising Committee tried to revive suspenders with this tempting portrait of a rotund alderman.

The novelty soon turned up in Michigan papers. The May 11, 1901 Traverse City Evening Record ran a large ad that included a plug for “a bran[d] new scheme for making suspenders invisible for summer wear without vests.” The June 13, 1908 Saturday Evening Post advertised “Se-No” invisible suspenders. Interurban train workers in 1914 were “permitted to go without their coats provided they wear invisible suspenders,” according to Henry Blake’s 1917 book “Electric Railway Transportation.”

Invisible or not, suspenders were passing out of vogue. “The sportsman first made the common-sense breakaway from suspenders, with the result that the belt is used almost entirely at present,” said the October 1920 issue of the New York-based Clothing Trade Journal. It continued, “It has been found that the suspenders can not only be done without, but that a belt is far more comfortable. It is true … that many men still wear suspenders, but they are largely those who have an abnormal abdomen, or who are unable to get away from timeworn habits.”

The March 1921 issue of Business magazine said, “There was a time when every man wore suspenders. Not so today. Today the man who wears suspenders usually is regarded as somewhat provincial.” The June 2, 1921 issue of Printer’s Ink added, “This whim of fashion among young men not to wear suspenders has gone so far that the big makers of young men’s clothing left off putting suspender buttons on trousers.” Belt loops were the new norm.

A coalition of alarmed suspender makers formed the short-lived Suspender Manufacturers’ Advertising Committee to try and revive their failing trade. They declared a week in October 1921 as National Suspender Week and planned a Christmas advertising campaign to try and convince shoppers to purchase suspenders. One pro-suspender writer in the July 1922 issue of the Railroad Worker trade magazine said:

Suspenders are like truth in many respects. At present they are “stranger than fiction.” They are often stretched. “Crushed to earth they will rise again.’ (Latest reports say they are again coming into their own). They also resemble honesty, inasmuch as ‘they are always the best policy.”

The nation did not agree. The number of suspender manufacturers fell from 100 in 1923 to 74 in 1935 and dwindled thereafter. The invisible suspender became truly invisible. It seemed as though the clothing item was forgotten for good.

But nearly a century later, it reappeared. The invisible suspender has been revived in the 21st century (you can order a pair online) not for decorum or comfort’s sake – but to help camouflage the abdominal avoirdupois that is unflatteringly accentuated by belts. The long-forgotten clothing item of the early 20th century returns for a stint in the early 21st century. May its wearers enjoy a general and pleasant elastic ease.

Mystery Artifact

In the last column’s comments, Cosmonicon and Irene Hieber correctly guessed that this is an accessories kit for a sewing machine.

Irene even narrowed it down, correctly, to an 1889 Singer – the very same treadle machine currently in my front room.

Talk about precision!

This month’s Mystery Artifact is a more prosaic item. Like the 1889 Singer sewing machine, it is still fully functional, though younger.

What might it be?

Take your best guess!

Laura Bien is the author of “Hidden History of Ypsilanti” and “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Look for her article on Coldwater School, a short version of which first appeared here, in the July/August issue of Michigan History Magazine. ypsidixit@gmail.com

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to keep our pants from falling down. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

it looks like a stapler, but that seems too easy…

That’s a Swingline Office Model isn’t it? Wasn’t it the first to tilt back and load staples easily?

No, that looks like the type you’d press the tab (on the right) and the staple holder would slide forward.

I was going to say it’s the handle for a mechanical doorbell but now I’ll go with TJ and say it’s a stapler.

I have the exact same model sitting right here on my desk. Labeled “Swingline Speed Stapler 3″ Slide back the side tabs and the head opens up and swings back to load

Yep, that’s a Swingline Speed Stapler #3. This design was first introduced by Speed Products in 1939 and was perhaps the first stapler made for easy replacement of staples. Speed Products became Swingline Inc. in 1956. The manufacturer name would be on the bottom and would determine if it’s before or after transition to the new name–my guess is after. This one looks much like mine except it has a slightly different strike plate.