Rezoning Process for N. Main Site on Agenda

Several additions to the Ann Arbor city council’s Aug. 20 meeting agenda came on Friday, after the initial Wednesday publication.

Former St. Nicholas Church at 414 N. Main in downtown Ann Arbor. It will be offered at public auction on Sept. 6.

And two of those items involve city ownership of land parcels – at opposite edges of downtown Ann Arbor. One of the properties is already owned by the city of Ann Arbor – the parcel at 350 S. Fifth. Situated on the southern edge of downtown, it’s also known as the Fifth and William parking lot (because it’s currently used as a surface parking lot in the city’s public parking system) or the Old Y Lot (because it’s the location of the former YMCA building).

The resolution would direct the city administrator to evaluate the parcel for possible public or corporate use; and if none is found, to report back to the city council with a timeline for the disposition of the property – based on state and city laws and policies. The resolution, sponsored by Stephen Kunselman (Ward 3), is somewhat unlikely to gain much traction with the council. That’s because it explicitly indicates that the city administrator’s efforts are to be independent of the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority’s Connecting William Street planning effort, which includes the 350 S. Fifth parcel.

The Connecting William Street project was undertaken by the DDA based on a directive from the city council, on a unanimous vote, given at its April 4, 2011 meeting. Kunselman voted for that planning effort to take place – but was also vocal at the time, as well as before, about his view that the Old Y lot should simply be put up for sale one way or another.

A second piece of property on the council’s Aug. 20 agenda is located on the northern edge of downtown at 414 N. Main St., near Beakes Street – the site of the old St. Nicholas Church. In 2006, owners of the site received approval for a planned unit development (PUD) zoning designation from the city council. The PUD would allow construction of The Gallery, an 11-story building (158 feet tall) that would include 224 parking spaces and 123 units of residential housing, 18 of which would meet the definition of affordable housing derived by a formula based on area median incomes.

That 414 N. Main property does not belong to the city. But the result of a foreclosure process has put it in the hands of another public entity – the Washtenaw County treasurer’s office. It’s being offered at public auction (on auction.com) starting Sept. 6 through Sept. 11, at a price of $365,051. County treasurer Catherine McClary told The Chronicle in a phone interview that the price includes the demolition costs – and that she’s selected a demolition firm to start the work. Asbestos abatement is already underway, and the demolition itself is expected to begin before the auction, though it will likely not be complete by then, as it will take 15 days.

What would the council’s resolution on the 414 N. Main property actually do? It would start the process to change the PUD zoning to that of the surrounding property, which is D2 (downtown interface) – allowing a maximum building height of 60 feet. The resolution, also sponsored by Kunselman, gives as part of its rationale the fact that the original developer is no longer pursuing the project.

If the property doesn’t sell at the Sept. 6 auction, it will be offered at a second auction. If it doesn’t sell at the second auction, the property would revert to the city. The city could exercise a right of first refusal and acquire the property for the minimum $365,051 bid – but that would require the city to make the purchase for a “public purpose.”

After the jump, we provide a bit more detail on the 414 N. Main property.

The Gallery

On Aug. 10, 2006, the city council approved a planned unit development PUD for construction of The Gallery at 414 N. Main. Had it been built, it would have included construction of two buildings – one 11-story building and another four-story building. [.pdf of PUD supplemental regulations]

It would have included 123 units of residential housing, with 18 of those meeting the definition of affordable housing derived by a formula, based on area median incomes.

The project also would have included 224 parking spaces, 57 of which would have been provided to the neighbor to the south, McKinley Inc.

McKinley and the developer of The Gallery struck an agreement that provides an easement on the four parcels that make up the property. And that easement guarantees access to 57 parking spaces by McKinley to the site. The easement is attached to the land, not its owner. So even though the owner has changed hands – because it’s owned now by the Washtenaw County treasurer as a result of the foreclosure process – the easement persists, along with its guaranteed 57 parking spaces. That’s an additional challenge for a developer, because those 57 spaces must be constructed – likely in some kind of deck structure – but won’t be available for the tenants of the building.

Four parcels of The Gallery project. Main Street runs north/south on the left side of this photo. The parallel street on the right is Fourth Avenue.

The property’s four parcels include three that front on Main Street, and a fourth one that fronts on Fourth Avenue. Fourth Avenue and Main Street are north-south streets running parallel to each other.

So part of the project site spans the entire block between Main Street and Fourth Avenue. Across Fourth Avenue from the project site, on the avenue’s eastern side, is Kerrytown Market and Shops.

The site plan for The Gallery approved by the city council is still valid – because it has been extended by administrative approval, most recently on Sept. 9, 2011. The property’s current owner, the Washtenaw County treasurer, would not conceivably try to build The Gallery with the currently authorized site plan and its PUD zoning, because the treasurer holds the property for the sole purpose of putting it up for public auction.

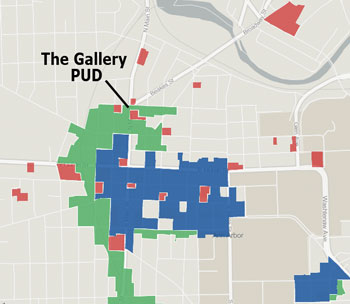

Zoning designations. Color key: blue, D1 (downtown); green, D2 (downtown interface), red, PUD (planned unit development). Kunselman’s Aug. 20 resolution would direct city staff to begin a process for rezoning The Gallery PUD to D2 (downtown interface), to be consistent with surrounding properties.

But if nothing changed, the new owner would be entitled to build a project similar to The Gallery. If the zoning were changed to D2 (downtown interface) – which is the eventual intent of Stephen Kunselman’s resolution – then The Gallery would not be possible. That’s because D2 zoning carries with it a limitation on building height of 60 feet. One of the arguments likely to be heard at the Aug. 20 Ann Arbor city council meeting is that nothing should be changed before the auction, because the PUD zoning and site plan might make the property more valuable.

By way of background, the “market value” of the property is around $2 million, and its “taxable value” is half that. The total tax burden in Ann Arbor, counting all the taxing jurisdictions, is about 45 mills. So a tax rate of about 45 mills on $1 million in taxable value would work out to roughly $45,000 annually.

An inspection of the city’s online property records shows that taxes haven’t been paid since 2007. And that five-year period of non-payment is consistent with McClary’s description of the property owing $255,000 in back taxes.

Forfeit, Foreclosure, Demolition, Auction

In a phone interview, Washtenaw County treasurer Catherine McClary reviewed for The Chronicle how the foreclosure process works. Key is the fact that in Washtenaw County, the treasurer is the foreclosing governmental unit (FGU). In some counties, the state of Michigan is the FGU for the county.

The property was turned over as delinquent on March 1, 2010. A year later, on March 1, 2011, the property was forfeited. The property was foreclosed in February 2012 on a court order from 22nd circuit court judge Donald Shelton. The owner had the opportunity to redeem the property through March 31, 2012, but did not. [.pdf of excerpted Public Act 123 of 1999]

The result of the foreclosure order is that the new owner of the property is the Washtenaw County treasurer. But the sole point of that ownership is to put the property up for public auction. The auctions must be held each year between the third Tuesday in July and the first Tuesday in November.

A property is first put up for auction at a “minimum bid” auction. The minimum bid is defined as the total amount of back taxes owed, plus the cost to bring the property to auction. For McClary, the cost of bringing the 414 N. Main St. property to auction will include the demolition costs. Of the $365,051, approximately $110,000 of that is the cost beyond the taxes – as the taxes on the property were about $255,000, she said.

Ordinarily, this North Main Street property would have been put up for auction in July, along with other “minimum bid” auctions in Washtenaw County. But McClary said she pushed the city to exercise its right of first refusal – to purchase the property at the “minimum bid” price. And because the city’s decision-making process takes some time, she’d agreed to delay the “minimum bid” auction until Sept. 6.

Other properties in Washtenaw County available for the Sept. 6 auction on auction.com include ones offered at $1,000. Unlike the North Main Street property, these are being offered for a second time, having not sold at the earlier “minimum bid” auction. McClary explained that she’s using $1,000 as the starting price this year.

So if the North Main property doesn’t sell in the Sept. 6 auction, it’ll be offered in October at a starting price of $1,000. But she noted she’d be attaching a $110,000 performance bond to that sale, to ensure that she recovers her demolition costs.

Part of what McClary also expects to get out of a sale price is the cost of a phase one environmental clearance. She pointed out that she’d taken care to ensure – as part of the contract with the company that performed the environmental clearance study – that the new owner of the property could rely on that clearance. Ordinarily, an environmental clearance can only be used by the person who paid for it. Being able to rely on an existing environmental clearance study is a value to the potential buyer.

McClary also sees the demolition of the existing building as adding value for a potential bidder at the auction. But based on her remarks on the phone, the main impetus for her to proceed with the property’s demolition is to eliminate the nuisance and blight that the building has become. She described her regular communication with Ann Arbor police chief John Seto, and the work of a social worker on her staff, who works with Washtenaw County’s PORT (Project Outreach Team) as they interact with the people who try to live on the long-vacant property.

McClary summarized the rationale for proceeding with the demolition: “So whether the city takes the property or whether developer buys the property, we know that the blight and crime is gone off of that site.”

If no one buys the property at either the Sept. 6 auction or (if necessary) the October auction, the property would most likely revert to the city of Ann Arbor.

But another possibility McClary raised was that the property could be put into a land bank. She observed that the Washtenaw County board of commissioners had voted to establish one, but had not taken the step of funding it or getting approval from the state. The Chronicle’s last coverage of this issue was from the Dec. 1, 2010 Washtenaw County board of commissioners meeting:

Conan Smith was nominated to serve on the board of the county land bank authority. The land bank – a mechanism used to help the county deal with foreclosed and blighted properties – has a somewhat convoluted history. The board first authorized it in 2009, but decided to dissolve the land bank earlier this year after they failed to reach consensus on issues of governance and funding.

After further debate spanning several months, the board revived the land bank in September, when they also passed a resolution calling for two commissioners to serve on the land bank’s board. That change requires state approval, which has not yet been authorized. When state approval is given, [board chair Rolland] Sizemore plans to nominate Wes Prater to serve on the land bank authority board, filling the second set allotted to commissioners.

Ann Arbor City Council’s Issues

Kunselman’s resolution would simply direct planning staff to initiate the rezoning process. The council would need to take two future votes – at a first reading and a second reading preceded by a public hearing – in order to rezone the property. The conversation around Stephen Kunselman’s resolution on the Aug. 20 agenda is likely to center around at least two issues: (1) the timing of a rezoning process; and (2) the appropriateness of a rezoning process, independent of timing.

If the property is to be rezoned, then it would be easier to do that while it’s in the county treasurer’s hands – because the city could count on treasurer Catherine McClary’s full cooperation. She told The Chronicle she’d be happy to request the rezoning of the parcel as the owner of the property, and that the city would “just need to tell me what to write in my letter!” But the timing McClary was talking about was between the auctions – if the property didn’t sell at the first auction. McClary didn’t venture an opinion about starting a process before the auction that would lead to rezoning.

One possible argument against approving Kunselman’s resolution now would be that it’s important to wait until the outcome of the Sept. 6 auction before taking any action. The best chance of the property being sold to a private developer – so the argument would go – is to leave the PUD zoning in place. The 57 parking spaces that must be provided on the parcel for McKinley is one challenge that could conceivably justify allowing a larger development than what D2 zoning would allow. That argument depends on the premise that such a development is desirable and beneficial – or at least that it’s a better alternative to letting the property languish.

Precisely because a developer could purchase the property and build a project similar to The Gallery is a possible argument for rezoning the parcel to D2 – so that such a project could not be built. If that argument is made at the city council table on Aug. 20, then it will likely appeal to the history of the A2D2 downtown rezoning process, which was given final approval by the city council in late 2009. The A2D2 zoning process, so the argument would go, reflects a broad community consensus about what the basic requirement of the downtown interface should look like – and that for the 414 N. Main St. property, that area should conform with D2 zoning and its height limit of 60 feet.

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of processes like public auctions – because our coverage isn’t sold to the highest bidder. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

Superb description of the entire process. Thanks. I am indebted to the Chronicle staff for covering such vital civic issues.