County Gets Info on Flooding, Shares Options

A meeting last week at Lawton Elementary School, in southwest Ann Arbor, fell the day before the one-year anniversary of significant overland flooding in the neighborhood. The flooding resulted from heavy rains last year on March 15, 2012. Last week’s meeting followed an earlier one held on Jan. 29, 2013.

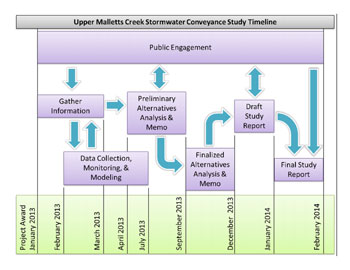

The meetings are part of a study of the Upper Malletts Creek watershed, being conducted by the office of the Washtenaw County water resources commissioner under an agreement with the city of Ann Arbor. The year-long study is supposed to culminate in a final report due to the Ann Arbor city council in February 2014. Water resources commissioner Evan Pratt was on hand at the meeting, along with other members of the project team.

In response to direction from a citizens advisory group that’s been formed for the project, the team used the March 14 meeting to introduce residents to the basic toolkit for stormwater management techniques. The general stormwater management practices described at the meeting – without trying to analyze which solutions might be appropriate for specific locations in the area – ranged from increasing the number of catch basins in streets to the construction of underground detention facilities.

At least 60 residents attended the meeting, and seemed generally receptive to the idea that some money might actually be spent on infrastructure projects to reduce flooding in their neighborhood: “If you want me to sign up for you breaking up my street and putting [stormwater management infrastructure] in there, just give me a consent form and I will sign it tonight!”

The project team is also still in a phase of gathering information about specific experiences that residents have had with past flooding problems. And the same technology platform – an online mapping tool – can be used by residents for logging future flooding events. For help in using a smart-phone app, one attendee volunteered her grandson “for rent” to other residents. Members of the project team also indicated they welcomed information submitted in any format – including letters, face-to-face conversation and phone calls.

But it was a missing follow-up phone call – expected from one resident who’d attended the first meeting on Jan. 29 – that indicated some continuing frustration about the city’s footing drain disconnection (FDD) program. The frustrated resident’s experience had been that after an FDD program sump pump was installed in his basement, he’d started having problems with a wet basement – problems he hadn’t experienced before. Project manager Harry Sheehan, with the county water resources commissioner’s office, extended an apology for the missed communication and an offer to arrange a site visit.

The FDD program removes a building’s footing drain connection to the sanitary sewer system and redirects that stormwater flow to the system designed to handle it – the stormwater system. The FDD program, which has been somewhat controversial, is not the focus of the Upper Malletts Creek study. But residents got an assurance that the additional volume of rainwater that goes into the stormwater system – as a result of the FDD program – would be accounted for in all the modeling that’s done as part of this study.

Meeting Overview, Context

This report begins with a legislative overview, and a summary of the introductory remarks from the March 14, 2013 meeting.

Overview: Precipitating Events, Funding

An arrangement for the Washtenaw County water resources commissioner to study the Upper Malletts Creek area was authorized by the Ann Arbor city council at its Oct. 15, 2012 meeting. The $200,000 cost of the study is to be paid for with city funds already held by the county water resources commissioner’s office.

The area to be studied, outlined in the agreement between the city and the water resources commissioner, included “the Malletts Creek Drain Drainage District in the Churchill Downs and Lansdowne sub-watershed areas.” Potential improvements mentioned in the agreement include detention, pipe upsizing, and green infrastructure.

Negotiations on that agreement with the water resources commissioner stemmed from a council resolution approved at its Aug. 9, 2012 meeting. That resolution directed city staff to start negotiations with the county to conduct the study.

The staff memo accompanying the council’s Oct. 15, 2012 resolution mentioned the heavy rains on March 15, 2012, which resulted in street flooding in that part of the city. The city council heard complaints from the public at its meetings after the flooding. A map of historical flooding in the city – obtained by The Chronicle through appeal of an initially-denied request made under Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act – shows that respondents to a survey conducted in the mid-1990s reported they’d experienced street flooding in the same areas that the flooding occurred in the spring of 2012.

Residents at the March 14, 2013 meeting wanted to know how big the March 15, 2012 storm was – from an historical perspective. They noted that on Scio Church Road there was water running through the yard, which hadn’t happened in the previous 20 years.

Ron Hansen, a Spicer Group engineer who’s working on the project, said that given the magnitude of the flooding, it was a very historic event. For many people, it was the most significant flooding they’d ever seen. But he’d heard from other people who said they’d had numerous floods over the last 20-30 years. The rainfall amount on March 15, 2012 was in the range of 1.7 or 1.8 inches in a two-hour period, Hansen reported. That doesn’t mean that the intensity over every house was the same as the intensity measured by the rain gauges, he allowed. And it was in the springtime, when the ground doesn’t absorb as much water – so you get more runoff.

Some frustration about the number of studies that have been done over the years was expressed at the March 14 meeting. And water resources commissioner Evan Pratt led off his introductory remarks at the meeting with an acknowledgment of that sentiment, noting that some attendees might be thinking, “Oh no, another study!”

Overview: March 14, 2013 Meeting Intro

Pratt asked for a show of hands of the roughly 60 residents in attendance – for those who’d attended the Jan. 29 meeting. From that he concluded that there were enough new attendees that it would be worth reviewing some of the information presented at that meeting.

He told the residents that they were in the right place if they wanted to stay engaged and help the project team work toward figuring out some real improvements that could be made so they didn’t have the same problems that they’d experienced last year on March 15, 2012, when there was so much flooding in the streets and in the yards.

Pratt allowed that he’d only been water resources commissioner for a few months, but told the group that he had been working on residential flooding issues for about 25 years. [Pratt was elected in November 2012 and took office at the start of 2013.]

One thing he’s learned in that experience, Pratt said, is that the residents at the meeting still know more than he and the consultants do about the problems in their neighborhood. His team is still trying to understand where the problems were and how bad they were on March 15, 2012. He ventured that they had a pretty good handle on it from previous data collected, supplemented by information collected at the Jan. 29 meeting – but the project team is still collecting information. He also offered to arrange that evening to visit anyone’s property if that’s what they wanted.

He ventured that those in attendance would like to head home and say, “Man, we’re done! I understand exactly how everything’s going to get fixed and there’ll never be water in the yard or in the street!” That’s not something he could promise that night, or at the end of the study, he allowed. But the project team would figure out some positive solutions so that if it rains again like it did a year before, residents wouldn’t see the same severity of the problem.

Besides Pratt, other members of the project team introduced at the start of the meeting included employees of the Spicer Group, the engineering consulting firm hired for the study: Ron Hansen, a professional engineer and surveyor; Tim Inman, who works with GIS mapping; and Steve Roznowski, a design engineer.

Handling communications, website and media work on the project are Josh Hovey, a vice president of Truscott Rossman and Lauren Zdeba, an account executive with the same firm. Hovey noted that the location of the meeting, Lawton Elementary, was Zdeba’s old elementary school – so she’d grown up in the neighborhood. [Responding to a query from The Chronicle about the school's mascot, Zdeba confirmed it was the Lawton Leopards. "Our rivals were the Dicken Dolphins!" she said, referring to the elementary school in the neighborhood just to the north.]

Project manager for the Upper Mallets Creek study is Harry Sheehan, with the water resources commissioner’s office. Also on hand at the meeting were city of Ann Arbor employees Cresson Slotten and Jennifer Lawson. Slotten is an engineer and manager of the city’s systems planning department, while Lawson is water resources manager with the city.

In his remarks toward the start of the meeting, Sheehan said the goal of the project is to manage stormwater better and reduce flooding: ” … essentially what we’re looking to do is take a look at what happened on March 15, 2012 and provide solutions to make the effects of that storm much more manageable.”

Overview: Stormwater Management Toolkit

Ron Hansen, engineer with the Spicer Group, described how the goal of the engineering study is to develop a recommended plan that could be implemented to reduce the probability of flooding.

The study would eventually identify the estimated cost of the recommended actions and weigh that against the benefit, he said. “It would nice to say we’re going to build a system that is so big that it’ll never flood again, but the reality of it is that would be cost prohibitive. When it comes to rainfall, there’s always the bigger and badder storm.” There’s always a chance of flooding, he said.

He also stressed that the solutions to be recommended should not adversely impact downstream property owners. The goal is not to push the problem downstream, but rather to manage the water within the study area, so that the flooding problems within the study area could be addressed without creating new problems downstream.

The goals are also to implement solutions that maintain or improve water quality, he said. Some of the solutions, he continued, would involve “hard engineering” approaches like installing new pipes. Other approaches are “softer” – such as installing rain gardens and infiltration-based systems. The key is to maintain and enhance water quality, he said. The recommendation should also be sustainable for the longer term – which means that it should be low maintenance.

Hansen then walked the March 14 attendees through a range of options for stormwater infrastructure:

- catchbasin enhancements

- street maintenance

- clean/repair existing drainage infrastructure

- enhance/modify existing detention management

- construct new surface stormwater detention

- construct new underground stormwater detention

- upsize/enhance storm sewer capacity

- bio-retention/rain gardens

He noted that they’d begin with low-cost options, like evaluating catch basins in streets, allowing that these might have a low impact as well.

He also described high-cost options like building underground detention facilities – which he described as big underground concrete boxes – or tearing up streets and backyards. He thought it was likely that some of that type of work might be called for, but the question is where to implement those solutions. And the location and type of facility would depend on the outcome of the engineering analysis and modeling of the study.

Along with the “hard engineering” approaches, Hansen indicated that “softer” approaches – like rain gardens – would be included in the options as well. Softer approaches would be included more than likely in addition to, not instead of, some of the harder engineering approaches, he said. He drew laughs from the audience when he said: “My gut feeling is you can’t solve this problem with rain gardens.”

Geographic Area of the Study

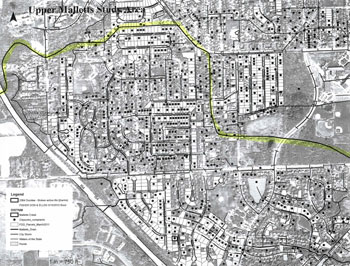

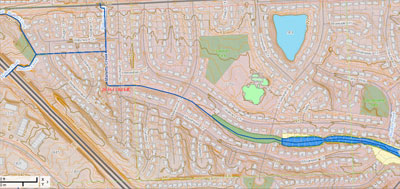

Harry Sheehan oriented the audience to the area of the study – the northwestern portion of Mallets Creek. He pointed out how I-94 crosses through the area of study. He ventured that most of the attendees at the meeting that night were probably from the city of Ann Arbor, but pointed out that the Mallets Creek watershed, and the area of the study, goes quite a ways past I-94, into the townships. It reaches all the way to The Uplands, he said, west of I-94 and up toward Stadium Boulevard, and in the upper righthand corner of the study area is part of the Pioneer High School property.

The blue line is Mallets Creek, Sheehan said. Describing Malletts heading upstream (from east to west), Sheehan note that at Landsdowne the creek is open water. But after it crosses 7th Street, it’s a piped system – continuing between Moorhead and Delaware, and across Churchill. It then makes a bend and goes through some backyards on the other side of Churchill Downs near Steeplechase, then goes through Churchill Downs Park. That’s where it opens up, he explained. There are two tributaries that split up in Churchill Downs Park – one of them goes north and one of them goes west, down by the Ice Cube and the Pittsfield branch of the Ann Arbor District Library.

Within the study area, the project team has mapped out areas of known flooding, based on previous information, but also based on information gathered at the first meeting on Jan. 29, Sheehan said.

He pointed out that while there had clearly been problems in the southeastern portion of the study area, that was not the only location.

Sheehan also pointed to problems that had been logged on Chaucer Court and up by the service drive on Scio Church Road. There were clearly a lot of locations to look at, he said.

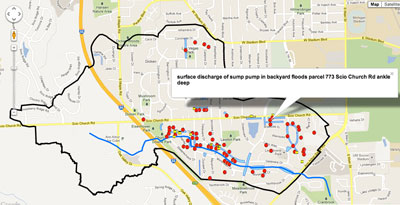

All the red dots on the “smart map” reflect problems reported to the project team at the Jan. 29 meeting, he said. That first public meeting on Jan. 29 was spent primarily collecting that kind of information from residents who attended, Sheehan said. The information would be used to create a model that accurately represents the events of March 15, 2012, and that can be manipulated to model solutions to managing the stormwater.

From the audience came a request that Sheehan define “flooding” – as it was including in the annotations on the map where problems had been identified. As a definition of flooding for the purposes of the study, Sheehan offered: “If the piped system is overwhelmed or surcharged, and the water exits the piped system onto the street and the yards, or if … the water is not able to get into the system.”

By way of additional background, the Washtenaw County online GIS mapping system includes a number of different layers, including aerial photography, topography, flood plains and drains. The following images derive at least in part from that system.

Geographic Area: West of I-94, Detention Ponds

Ron Hansen responded to a question from a resident about the part of the study area that’s west of I-94. The resident wondered if the drainage from that area were eliminated, would it reduce the flooding in the triangle of Scio Church Road, Main Street and I-94?

Hansen said he didn’t have the exact answer to that. The resident gave some further background for his question, noting there’s not a lot of open land within the city limits to create stormwater detention facilities. Even if the school yard at Lawton Elementary were torn up, “that wouldn’t give you what you want,” he ventured. But on the other side of I-94 there’s a lot of open land, he said. He asked if the project team was considering underground detention or detention ponds for that area. On the opposite side of I-94 is one place where those kinds of projects could be undertaken, he felt. The resident ventured that imminent domain would have to be invoked for many of the possible sites, because they’re on private land.

Harry Sheehan allowed that if you remove water from the system or you delay its entry into the system, that will have an impact. So large-scale stormwater facilities and large-scale rain gardens – which is to say, wetlands – are something that could be contemplated in the area west of I-94. Whether eminent domain would have to be used wasn’t clear, he continued, pointing out that there is some public right-of-way and land that can be purchased. There are also some smaller pockets within the city boundary, he pointed out, such as the area just north of Churchill Downs up by Scio Church Road, where the open channel of the creek runs.

The audience member followed up by saying he was a big fan of detention ponds – because he lives next to one, which is bounded by Scio Church, 7th Street and Greenview. Most of the runoff in the neighborhood runs off into that detention pond, he said. During the dry season, the pond level is down and during the rainy season it’s up. The detention pond controls the water in his immediate neighborhood, so he felt the same solution would work in many others. Hansen added that detention could be feasible, but the concept of diverting or shutting the water off is not too feasible – because if you diverted the water coming from west of I-94, that would push it onto somebody else’s property.

Responding to a question about how many acre-feet of detention ponds would be required, Hansen said that’s one of the questions the project team is studying. The goal is eventually to be able to answer all the questions like that – but they wouldn’t be able to provide answers that evening. The final report on the project will be done in February 2014. It will take time to calculate the acre-feet. It’ll take time to identify where feasible stormwater detention facilities could be placed.

Right now the team is still partly in the information-gathering phase, Hansen explained. The team is also starting to do its modeling and monitoring work. After that is done, the team will begin the preliminary analysis phase. At that point they’ll be able to make statements like: If we put 20 acre-feet of detention at this location, here’s the level of service you’d get. That answer is still a few months in the future, he cautioned. He described five or six additional neighborhood meetings that would take place from now through February 2014.

Stormwater Improvements Funding

Residents at the March 14 meeting wanted to know if funding would be forthcoming and when it would be forthcoming.

Stormwater Improvements Funding: Utility Fees, CIP

Harry Sheehan indicated that the funding stream for the city of Ann Arbor is set by the stormwater utility rate that shows up in your water bill. His own stormwater utility bill is about $25 a quarter, he said. In the city’s capital improvements plan (CIP), Sheehan explained, the first two years are budgeted. The funding from the stormwater utility fee would come as projects are defined in connection with the Malletts Creek study and placed in the CIP over the course of the next few months. Within the CIP, projects are prioritized, he said, and those that are prioritized for the first two years of the CIP would be budgeted.

The number of projects that are programmed in the first two years of the CIP are those than can be afforded with funds from the current stormwater utility, Sheehan said. It’s been possible to double the amount of projects undertaken, because the city and county use the state’s revolving loan fund, and some grant money that goes along with that. A couple of projects that will include stormwater management components are already budgeted in the neighborhood within the current two-year CIP cycle: Scio Church Road from 7th to Main Street; and 7th Street from Scio Church Road to Greenview.

From the funding summary of the CIP [both projects are scheduled for funding in FY 2016]:

UT-ST-14-13 Scio Church Storm Sewer Improvements (Main to 7th) $750,000 UT-ST-14-22 S 7th (Greenview to Scio Church) $650,000

-

For other projects, Sheehan described how deeper soil borings can be done to find out exactly where the groundwater is, relative to the surface, and to locate any sand seams.

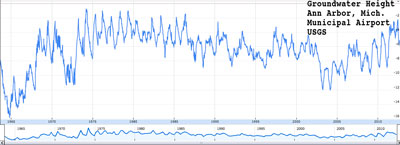

By way of additional background on groundwater, it’s measured on a regular basis at the Ann Arbor municipal airport. In the last 10 years, it’s shown a rising trend – something that factored into a recent discussion by the city’s park advisory commission on issues like the location of a tennis court in Windemere Park. Daily measurements from 1963 through 2012 are available on the USGS website. [Google Spreadsheet and interactive graph]

Sheehan described collecting video data from the storm sewers and capturing flow data, so it can be determined how much water needs to be stored at different locations throughout the neighborhood.

Stormwater Improvements Funding: Street Projects

Earlier in the meeting, Sheehan had pointed out that the road right-of-way represents an opportunity for stormwater management. Streets have a useful life, and when they have to be reconstructed, that’s a chance to increase the size of the detention and conveyance system underneath the street, he explained.

Harry Sheehan, environmental manager with the Washtenaw County office of the water resources commissioner.

If that kind of stormwater improvement is part of a street reconstruction project, Sheehan explained, it can earn the project additional points in the priority rating system used in the city of Ann Arbor’s capital improvements plan (CIP). If a street needs to be reconstructed because the road surface needs to be replaced – which is typically why a street would be replaced, he noted – it will be placed in the CIP. But if there’s utility work that needs to be done as well, that accelerates the street project within the CIP.

Underneath the roadway, Sheehan said that improvements would be made by installing larger-sized pipes or underground storage – similar to what would ordinarily be found in porous pavement systems. If there’s water coming under the street from another neighborhood, you might not be able to store it all, he said, but you might be able to put in some swirl concentrators to remove some of the pollutants in the water. Those are the kinds of stormwater management systems that would be deployed under roadways.

Responding to a follow-up question from the audience, Sheehan described how anytime there is a street reconstruction project, the different components of the project are funded by their respective funds – street reconstruction, sanitary sewer work, drinking water and stormwater. Only the part of a street reconstruction project that can be associated with stormwater management is paid for out of the stormwater utility, Sheehan explained.

Stormwater Improvements Funding: Can Money Be Spent?

An additional follow-up question focused on the city policy for expenditures on stormwater improvements: Was it the case that money was not being spent on stormwater improvements in this part of town, because they were considered speculative investments – and for that reason they weren’t going to get done? The question was prompted by an Ann Arbor Chronicle report of a May 11, 2011 briefing that systems planning engineer Cresson Slotten had given the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority’s partnerships committee. In that briefing, Slotten had explained that the basic utility rates could not fund replacement of utility systems before they’d reached the end of their useful life – things like upsizing water mains to support future development.

Sheehan gave an assurance that money is being spent every day on stormwater improvements. A project is being done right now on Traver Creek, he said. Four road projects are planned for this construction season in the city that have stormwater management components, he pointed out. It’s not accurate to say that money is not being spent on stormwater improvements, Sheehan said.

The response from the questioner was that it’s music to his ears to hear that stormwater utility money can actually be spent on stormwater improvements: “If you want me to sign up for you breaking up my street and putting something in there, just give me a consent form and I will sign it tonight! You can put it in my backyard – you can put it anywhere you like!”

Stormwater Management Codes

At the March 14 meeting, Cresson Slotten – an engineer and manager of the city’s systems planning unit – was challenged by a resident to describe what the city has done to keep more rainwater from “washing down into this neighborhood.” The resident wanted to know: What have you done? What laws have you put in place?

Slotten explained that in terms of ordinances, rules and regulations, Chapter 63 of the city code is the part that deals with stormwater management. The chapter overall deals with soil erosion, Slotten explained, but a key piece of soil erosion is stormwater and stormwater management. He reported that the first piece of Chapter 63 was put in place in 1979, but since that time, it’s gone through a tremendous evolution. In the 26 years Slotten has worked for the city, he said, it’s been revised at least five times.

By way of illustration, Chapter 63 includes different requirements for on-site stormwater detention, depending on the amount of impervious surface in the project:

Sites proposed to contain:

(i) Impervious surfaces greater than 5,000 square feet and less than 10,000 square feet require retention/infiltration only of the first flush storm events.

(ii) Impervious surfaces equal to or greater than 10,000 square feet and less than 15,000 square feet require retention/infiltration only of the first flush and detention only of bankfull storm events.

(iii) Impervious surfaces equal to or greater than 15,000 square feet require retention/infiltration of the first flush, and detention of bankfull, and 100-year storm event. Detention facilities designed for the 100-year storm event shall include a sediment forebay.

Slotten explained that when a new project is proposed – a new office plaza or a new subdivision – the project must include the required stormwater management facilities to hold the water and to slow it down. To illustrate, he described a little neighborhood on the north side of Scio Church Road for which he’d done the stormwater review back in 1988 or 1989. It was a development with about a dozen single-family homes. A certain amount of stormwater detention was required on the site, he said. The amount of impervious surface was calculated – for the driveways, the roof area, and the little road. From that amount of surface, the required stormwater detention was calculated. Responding to a question from the audience, Slotten said it was not “just a guess” but rather had been calculated out by engineers.

Slotten also noted that in the townships, similar rules apply. Washtenaw County also has a set of stormwater regulations, he said, which the city has now adopted. The resident who’d prompted Slotten’s description of the regulations ventured: “These rules don’t work.” Slotten responded by saying that’s why they continue to evolve.

Footing Drain Disconnect (FDD) Program

From the audience at the March 14, 2013 meeting, some questions arose about the city of Ann Arbor’s footing drain disconnect program.

FDD Program: Background

The city of Ann Arbor has separate sanitary and stormwater conveyance systems.

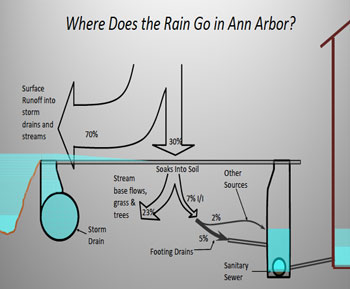

Where rain goes: 70% runs off, and 23% soaks in, becomes part of underground flows or is absorbed by vegetation. It’s the remaining 7% of the rainwater that causes a problem for the sanitary sewer system – because the sanitary system is not designed to handle that kind of volume. (Diagram from the city of Ann Arbor.)

However, during construction of new developments before 1980, footing drains – permeable pipes buried around the perimeter of a foundation, roughly at the depth of a basement floor – were frequently connected directly to the sanitary sewer pipes. Those connections were convenient to make, because the footing drains and the sanitary sewers are buried at roughly the same depth.

However, during very heavy rains, that configuration leads to a volume of stormwater flow into the sanitary sewer system that it’s not designed to handle. That can cause two problems.

First, near the point where the extra water is entering the sanitary system, it can cause raw sewage to back up through the floor drains of basements.

Second, farther downstream at the wastewater treatment plant, the amount of water flowing into the plant can exceed the plant’s capacity. That can result in only partially-treated wastewater being discharged into the Huron River.

It was wastewater discharges into the river that led the city to agree to an administrative consent order with the Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) to establish a way to offset the impact of new connections to the sanitary system required by new developments.

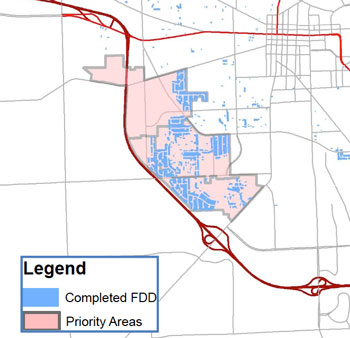

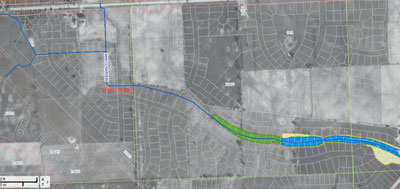

Footing drain disconnect (FDD) priority area in the southwest of Ann Arbor. Other priority areas, where nearly all the disconnections have been completed, lie in the northeast part of the city. The area of study for the Upper Malletts Creek study overlaps a large part of the FDD priority area. (Diagram from the city of Ann Arbor.)

That program essentially requires developers who are building projects that place additional burdens on the sanitary sewer system to pay for a number of footing drain disconnections elsewhere in the city, according to a formula. A city council resolution from Aug. 18, 2003 authorized the consent order with the MDEQ.

The footing drain disconnect program was targeted initially in five neighborhoods that accounted for about half of all reported basement sewage backups.

Since implementation, 2,538 footing drains have been disconnected, including nearly all of the houses in three of the five neighborhoods. In the two other areas, between 55% and 60% of footing drains have been disconnected.

The city council decided on Sept. 17, 2012 to suspend temporarily the footing drain disconnect program.

And at its Feb. 4, 2013 meeting, the city council authorized a roughly $1 million study of Ann Arbor’s sanitary sewer flows – meant to assess the impact of the decade-long footing drain disconnect program. The point of the study is to see how well the FDD program has worked: Has it had more impact or less impact than expected? Have residents’ preferences changed with respect to how they’d like to see the issue addressed?

The decision to suspend the FDD program came in the context of complaints from residents in the area of the current Malletts Creek study – about overland flooding in spring of 2012 as well as earlier.

The FDD procedure includes the installation of a sump to collect water from the footing drains – which previously fed into the sanitary system – and a pump to move the water from the sump to the stormwater system. And in some cases, the pumps were reportedly not able to keep up with the influx into the footing drains. In other cases, the discharge of the pumps reportedly exacerbated the overland flooding.

FDD Program: Increased Challenge for Stormwater Management?

Responding to a question from the March 14 audience, Ron Hansen said the impact of FDD is being considered as part of the Upper Mallets Creek study. He couldn’t, at this point, say if the FDD program is impacting the stormwater system. He hoped to be able to provide more information at upcoming meetings.

Evan Pratt also responded to the question, saying that regardless of what you think of the FDD program, there’s a sense that if the stormwater pipe is already full, then the water volumes associated with the FDD program don’t really matter – whether it’s a small or large amount that’s being pulled out of the sanitary system and put into the stormwater system. If the pipe is already full, then all of that FDD amount – whatever it is – will not fit into the stormwater pipe, Pratt said. He assured the audience that the study would calculate the FDD amount, and the design of improvements would consider how much water is getting moved from the sanitary system into the stormwater system. “That will absolutely be considered,” he concluded.

Responding to a follow-up question, Pratt indicated his understanding was that the city of Ann Arbor had placed a moratorium on the FDD program. But he noted that a certain number of disconnections had already been done under the FDD program. Pratt said the project team would work hard with the citizens advisory committee to get a clear consensus on the calculated amount of additional FDD water that’s being pushed into the storm drain – over and above what comes off the surface runoff. The design improvements will need to account for that amount, too. Like Hansen, Pratt indicated that he couldn’t at this point say if it’s a huge number or a little number – but in general he didn’t feel like it was an amount that should overwhelm the system.

Related to that, Pratt noted that there was overland flooding in the area before the FDD program was implemented in the early 2000s. It’s the project team’s understanding that during heavy rains in 1971, for example, water flowed down Churchill and Wiltshire streets. But he allowed that the additional FDD flow into the stormwater system was a legitimate concern: If the pipes are full, then any amount of water makes the problem that much worse.

FDD Program: Developer Mitigation

Cresson Slotten of the city’s systems planning unit was called on by a resident in the audience to explain the FDD credit system for developer offset mitigation. Slotten responded by explaining the formula for the developer mitigation program. The formula requires that for every 1,000 gallons of additional sanitary sewer flow a new development might cause, that amount plus 20% – or 1,200 gallons – has to be mitigated by performing footing drain disconnection elsewhere in the city.

Although some dissatisfaction was expressed with the amount of detail provided about the credit system, the resident seemed content to leave the issue for another time.

FDD Program: No Follow-up Phone Call

One resident at the March 14 meeting expressed concern about his experience with the FDD program. Since an FDD sump pump had been installed, he said, his basement gets wet even with routine rainfall. He’d attended the Jan. 29 meeting, and talked to a number of people who’d assured him they’d make a follow-up call: “You know who I heard from? Nobody.”

Harry Sheehan recalled talking with the resident, saying that he’d spoken to the resident and to three other people. He’d wanted to get the resident’s address, to compare it to the database of complaints logged before the FDD program was started. That database goes back to the early 1950s.

Flooding complaint map plotting data as far back as the 1950s. Each black dot is a complaint that was logged about water.

Sheehan said if he’d told the resident he’d follow up with a phone call, that was Sheehan’s error. He’d just wanted to see if there was a complaint prior to the FDD program for any of the four addresses that fit the category of apparently new wet basement problems arising after the FDD program. None of them had a history of prior complaints, Sheehan reported.

Sheehan also recalled talking to the resident about having an engineer come out to the resident’s property. If the resident still wanted to have an engineer come out, Sheehan still wanted to do that. Sheehan apologized for not making the follow-up connection. The resident responded: “You’re going to have a pretty big problem if you don’t call me and my basement floods. I’ve been struggling with this too long, and every meeting I come to I get madder and madder.”

Next Steps?

The project team described next steps, but residents were also interested in finding out if there’s anything they could do immediately to help improve the situation.

Next Steps: Immediate

Some residents wanted to know what could be done right now. Evan Pratt acknowledged that any projects that eventually could be implemented would not be started now, or even in February 2014, when the report was due. As he’d walked through some of the areas of the neighborhood, he’d thought that in some places maybe a big landscape berm could work, but he wasn’t really sure if that would be a good idea.

Harry Sheehan described the March 15, 2012 storm as a 10-year storm in engineering terms. And he said that as the days go by, this area is getting out of a window when rain might be falling on partially frozen and saturated ground. Still, residents wanted to know what they could to mitigate damage, if a similar storm were to strike this year.

Sheehan told residents there were a limited number of things that could be done. If a catch basin on the street is blocked, for example, that could be cleared. He told residents that if they weren’t able to do that themselves, to give his office a call.

Next Steps: Study Process

Sheehan described some of the next steps, including soil borings and flow monitoring, knocking on doors and collecting additional information.

Soil boring data, including groundwater levels, will be collected as soon as the weather warms up a bit, Sheehan said. The information collected to date will then be compiled into a draft alternatives analysis to put out to residents and the citizens advisory committee. “It will be rough, but it will be more spelled out than what you’re seeing here, which is just categorical management practices.”

More numbers will be crunched based on reaction to that draft analysis. At that point, a revised draft will be created that will be roughly 90% complete. That version will include some associated costs and expected impact of the improvements. Another public meeting will take place to discuss that draft, he said. After that, a draft of the final report will be made and a public meeting will be held to get feedback on the report. A final report will be made by February 2014, and a public meeting will be held on that final report before it’s forwarded to the Ann Arbor city council.

Sheehan stressed that feedback can also be provided along the way by email if people get tired of attending the public meetings.

The Chronicle could not keep its head above water without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public issues like stormwater management. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

It is excellent reporting like this that makes me proud to provide regular financial support to the Chronicle. Thank you for providing such clear background information and concise reporting of the content of this meeting.

I also applaud the County Water Resources Commissioner. I was impressed by the manner in which he, his county staff and their consultant interacted with members of the community. They have earned a level of credibility that is lacking in the City’s FDD program.

“A map of historical flooding in the city – obtained by The Chronicle through appeal of an initially-denied request made under Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act…”

Can ANYONE on City Council stop this nonsenseofn denying FOIA requests? You would think someone in City Government was trying to hide public information. Not very comforting as this effort to study this flooding fiasco moves forward.

Re (2), As Dave noted in a previous column: “But we think it’s to the credit of the city of Ann Arbor that the administration is currently engaged in a revision to the administrative policy on FOIA response.” [link]

The important question is whether the FOIA policy review will remove barriers to obtaining public records or just change the policy to create different barriers.

I have seen the detention basins across I94 full of water even during dry spells although at times they are almost empty. These may need attention to capture more water before it flows across the highway.

An option the city has started using, porous pavement on roadways, could potentially be used as full course porous on shoulders of I94 with a friction course on the roadway for the west side of Ann Arbor.

The shoulders would handle all the water run off of the highway, the friction course would detoxify the runoff, provide up to 70% noise reduction, much better traction. The shoulders would detoxify and capture all the runoff. This highway would also provide greatly reduced heat island, less salt use and no heat shock to waterways.

Our neighborhoods would quickly increase in value from flood hazard reduction and health quality of life improvements from much less noise from the highway.

This type of highway design has been shown to cost less and preform better then conventional designs.

And I94 is slated for work this summer! MDOT has shown interest in this in recent years and it includes porous pavements for some uses in its BMP Guide.

Sound walls have been discussed for this section of I94, this would cost much more and preform much less effectively.

Seems we may have a large constituency that would overwhelmingly support the I94 changes. The Mallets and Allen’s Creeksheds would both receive greatly needed flood hazard and pollution reductions not to mention the quality of life improvement.