In the Archives: Woodlawn Cemetery

Editor’s Note: Laura Bien’s regular column this month would be suitable for publication as a Veterans Day column, on Veterans Day itself – which is observed on Nov. 11. But we’re publishing the piece in Bien’s regular rotation as a way of noting that it’s not required to wait until Veterans Day to remember the service of veterans.

A rumble builds into a growl. Silver flashes between treetops and a leviathan emerges into open sky. The magisterial craft draws gazes below, as it did seven decades ago, but this time without fear. Leaf-rakers in eastside Ypsilanti yards pause to watch its unhurried passage.

In its periodic passenger flights ($425 per person) and summer airshow circlings, the B-17 bomber passes within sight of 150 additional upturned faces. Beneath the roar of the polished martial icon lie some veterans, now silenced, and seldom remembered as part of the Greatest Generation. Their ambitions and bravery were likely scorned in their day and largely forgotten in ours.

They were laid to rest in a now-abandoned, segregated cemetery.

Just south of Ford Lake and east of the Ypsilanti Township Civic Center lies Woodlawn Cemetery. To drivers on Huron River Drive, it flits past as a grassy field. The adjacent dead-end dirt road Hubbard extends to the cemetery’s far southern end.

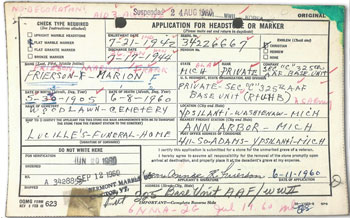

From that vantage point, only two man-made features rise above the site’s uneven surface. One is a homemade wooden cross bearing worn cream paint and stick-on mailbox letters spelling “BERTHA CAMPBELL.” The other is a small American flag. A brass military grave marker underneath is labeled “MARION F. FRIERSON” followed by Army acronyms and dates.

The land where Frierson lies was purchased in 1945 by local Second Baptist Church pastor Garther Roberson Sr. [and Rhonenee]. The location “was convenient and close to the main road,” recalls Roberson’s son Garther Roberson Jr., current pastor of Ypsilanti’s Mount Olive Church, in a personal phone call. The site lay near Second Baptist and Ypsilanti’s south side, where for at least the first half of the 20th century black citizens of Ypsilanti were redlined.

Oral histories collected by distinguished onetime Ypsilanti historian A. P. Marshall offer many examples of racist restrictions placed upon black Ypsilantians. Job prospects for blacks were largely limited to menial labor, as decades of Ypsilanti census forms attest. “When we were growing up,” said Garther Roberson Jr. in an oral interview he gave in 1981, “it was understood that a store would not hire black people to be cashiers, salespersons, or managers.” Many male black residents tried to earn money as day laborers or factory workers.

Often families, especially if new in town, lived several to a South Side home, another reality visible on old census forms. Ypsi banks would not give mortgages or even home improvement loans to black residents, a fact mentioned by Roberson in his oral interview and in those of other black residents. This financial bottleneck continued well into the 1950s. Ypsilanti also had more than one explicitly whites-only subdivision. The 1941 deed to the College Heights subdivision, for example, stipulates that “No person of any race other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any premise . . .”

Several oral histories in the Marshall collection attest to Garther Roberson Sr.’s strong influence in obtaining jobs for black residents and working with white and black Ypsilantians to improve the community. Part of this effort was his purchase of Woodlawn, so as to offer black residents, as his son told the author, “a place where people of color could have a decent and dignified burial.”

The records of Woodlawn interments were lost in a fire years ago. After the 1955 death of Garther Roberson Sr., whose grave marker lies at the site’s center, the cemetery association he formed went bankrupt. In 1970, an inspector from the State Cemetery Commission, who was investigating reported neglect, estimated that Woodlawn contained 150 graves. In 1981, three members of the Genealogical Society of Washtenaw County, Kenneth Coe, Martha Kacanek, and Karen Walker, conducted a cemetery reading. They recorded 76 names. As of mid-October of 2013, various other grave readers’ 2007-2013 contributions to the Woodlawn section of FindAGrave.com totaled 29 visible graves. When my husband and I visited in late October of 2013, we found only 21.

Among the holdings of the National Archives are the original forms used to request a military grave marker for a deceased veteran. The collection includes 14 marker requests for black veterans buried at Woodlawn (the National Archives acknowledges that its records are not complete; there may have been more requests). Of these 14 markers, eight were seen by the genealogical group in 1981. Four of those eight are visible today. As the stones continue to disappear, it is worth remembering the veterans for whom the markers were requested.

Seaman recruit Maurice Marshall enlisted in the Navy July 16, 1952. He was honorably discharged from his service during the Korean War on November 9, 1955. His wife Florence survived his death in 1962. Another Korean War soldier, Army Private First Class Paul Davis, served from November 1951 to August 1953. (Garther Roberson Jr. is also a Korean War veteran).

Among the cemetery’s WWII vets, Private Haywood Brown, Jr. served at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. A few months after he enlisted, the last class of black pilots graduated and the base was deactivated the following summer. Though Brown could not become a pilot, even serving at the Tuskegee air base is today regarded as so prestigious for its era that there is a special term for anyone who served on the base, pilot or no: DOTA, or “documented original Tuskegee airman.”

Private Marion Frierson also served in the Army Air Force, the WWII-era direct predecessor of the modern Air Force. He served for two years on an airbase in Marianna, Florida.

Private First Class David Atkins served in the 25th Chemical Decontamination Company. After two years of service at this dangerous work, he died in 1949 at Walter Reed Hospital.

Private First Class Bennie Cartwright and Private Paul McCarter both worked for quartermaster supply companies in Mississippi and Alabama respectively, which were Army units that provided food and supplies to soldiers. Cartwright received a Good Conduct medal.

Private First Class Ulysses Webb was also stationed stateside, in Missouri. So was Private First Class Fred Carter, who served as a truck driver in North Carolina. Black soldiers were disproportionately assigned to stateside service for the first part of WWII due to a prevailing misconception that they were not as capable of standing the rigors of combat. Because of this stateside bias, fewer black soldiers had a chance of earning many medals.

Staff Sergeant Paul Cunningham did travel overseas – but was relegated to a laundry corps. Nevertheless, he was honorably discharged with a good conduct medal, a World War II Victory medal, one medal whose acronym defied this author’s research, and a European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign medal with 5 Bronze Stars indicating participation in five overseas campaigns. The Victory medal and the EAME relate to time of service, but the good conduct medal is one of merit, and it should be further noted that many black soldiers who did fulfill the terms of time-of-service medals still never received them after the war.

The oldest military graves in the cemetery belong to WWI vets. Private Lander Bennett served in a Kentucky quartermaster corps; his widow survived him and requested the grave marker. Corporal George Thomas served in a motor pool at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. Private Cleo Cummings served in the 157th Depot Brigade in Alabama. Private William Brooks was stationed at Michigan’s Fort Custer in the 160th Depot Brigade. Even in an era that saw a deterioration of the treatment of black Americans and the second rise of the KKK – which included local mass “klanvocations” in Flint, Jackson, and a proposal for one in Ypsi – Brooks was so intent on joining the Army that he added a year to his birthdate on his enlistment form so as to meet, barely, the age requirement.

Bennett’s and Brooks’ Armistice Day occurred almost one century ago. Now called Veteran’s Day, the commemorative holiday on November 11 is a fitting time to remember those who responded to discrimination, the threat of violence, and grave disservice – with service.

Mystery Artifact

Last column three readers correctly guessed that the item in question was a shoemaker’s last, or form: Rebecca, Jim Rees, and cmadler.

Jim commented that the iron last looked exceptionally small, noting “a woman’s shoe with a 7.5-inch last would be a size 1.5.”Perhaps it was a last for making children’s shoes.

This time we have artifact with several component parts.

This artifact may be seen somewhere in Washtenaw County within an interesting display, but where? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Hidden Ypsilanti” and “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Contact Laura at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to help remind readers of those who’ve been forgotten. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

It sure looks like a WWII Army field ration of some kind. The closest match I could find is the “10-in-1″ or K ration.

Interesting guess, Jim. Thank you for reading!

Laura,

When you say “As the stones continue to disappear, it is worth remembering the veterans for whom the markers were requested.” Do you mean the markers are being stolen, subsumed into the ground, what?

Are the requests for new headstones going to/being handled by the Pentagon? Which office is handling that? Do you have a contact?

Thanks for the article.

Agree with Jim, but that appears to be a bottle of Iodine in the middle. Maybe a kit for a fallout shelter in the 50′s? Though the matches with the plug to buy Victory Bonds would put it to WWII the iodine suggests otherwise. The cigarettes seem oddly small, they are usually larger than that — is it the candy variety?

Cosmo, WWII ration cigarets came in packs of three or nine. Iodine was included in some rations for water purification. Also the condom suggests this is for soldiers, not civilians.

I did a little digging. The Ypsilanti Township online property database shows the street address as just

S HURON RIVER DR

YPSILANTI, MI 48197

and lists the owner as

WOODLAWN CEMETERY

YPSILANTI, MI 48197

The site is parcel # K -11-21-403-001

If you want to find it on a map, find Hubbard Street and South Huron River Drive, the cemetery is on the east side of Hubbard. There is a house at 7784 South Huron River Drive that is just across Hubbard from the cemetery.

Canton Township and the Michigan Historic Preservation Office together created a 200+ page guide to preservation of Michigan cemeteries. It’s online here: [link]

Describing the marker as brass, while the color appears to be consistent with the marble requested on the form you show is counterproductive to the spirit of the article. Theft of all copper alloys is a huge problem.

Timothy: You are right; I should have been more clear and I appreciate your calling that out. The markers appear to be sinking into the earth. My husband and I found a few markers that had just a tiny corner or so showing amid the grass. There are also many depressions in the earth that seem to indicate gravesites.

So far as requesting new headstones: I know that over at Highland Cemetery, an independent group requested and received modern headstones for those of old headstones for black Civil War veterans. I have very mixed feelings about the replacement of the old headstones for the new.

Cosmonicon: The cigarettes are not candy; it is a mini-packet of 5. Interesting guess…

George: Thank you for the info. Washtenaw Co. property lookup gives a hint as to the clouded question as to the ownership of this parcel. Boildown: it is in limbo.

Jim: Thank you for the additional info, and thanks for reading.

Thank you for this very informative post. There are really so much that we should know about these cemeteries. These cemeteries are home to a lot of veterans that have long been forgotten because of some vanished gravemarkers.