Greenbelt Group Briefed on Bioreserve

Ann Arbor greenbelt advisory commission meeting (Feb. 6, 2014): Kris Olsson, an ecologist with the Huron River Watershed Council, was on hand at GAC’s meeting to provide commissioners with an overview of the HRWC’s bioreserve project.

Kris Olsson, a watershed ecologist with the Huron River Watershed Council, at the Feb. 6, 2014 meeting of the Ann Arbor greenbelt advisory commission. (Photos by the writer.)

The aim of the project is to map, prioritize and encourage protection of the remaining natural areas in the Huron River watershed. The entire watershed covers about 994,000 acres. Of that about 247,000 acres are in the bioreserve. More than 1,700 sites have been mapped as potential natural areas.

The Ann Arbor greenbelt program is one of several partners in the project. Olsson told commissioners that the HRWC hopes this data is used to help land preservation programs like the greenbelt make informed decisions about how to protect natural areas.

Also during the Feb. 6 meeting, Ginny Trocchio – who provides staff support for the greenbelt program – briefed commissioners on the screening and scoring criteria used to review potential acquisitions for the greenbelt program. She reviewed characteristics that result in higher scores for property. For example, sites that receive higher scores have 3-4 natural features (stream corridors, woodlots or rare species), are located within 1 mile of the Ann Arbor city limits, and are located within a township or village that has passed a purchase-of-development-rights (PDR) ordinance.

Trocchio also reported that work on the greenbelt program’s new landowner registry is continuing.

The 90-minute meeting included a closed session lasting about 30 minutes. No votes were taken on potential land deals after commissioners emerged from closed session.

Bioreserve Project

Kris Olsson, a watershed ecologist with the Huron River Watershed Council, gave a special presentation to GAC about the HRWC’s bioreserve project. In introducing Olsson, GAC chair Catherine Riseng noted that they both also serve on the Washtenaw County natural areas technical advisory committee (NATAC), which helps oversee the county’s natural areas preservation program.

Olsson began by giving an overview of HRWC. It’s a membership organization, which includes individuals and entities like the city of Ann Arbor. [GAC member Jennifer Fike is HRWC's finance manager.] The nonprofit was started as a council of governments in 1965 under state legislation designed to protect the Huron River and its tributaries, lakes, wetlands and groundwater. She encouraged commissioners to look at HRWC’s website for a full description of its projects, programs and services.

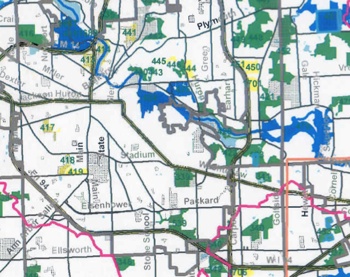

Detail of a Huron River Watershed Council bioreserve map, indicating areas of high priority (blue), medium priority (green) and low priority (yellow). Image links to .pdf file of complete map.

One of those projects is the bioreserve. The city’s greenbelt program is one of several partners in the bioreserve project, Olsson explained, along with all of the land conservancies in the watershed, the Washtenaw County parks & recreation commission, and other groups. The aim of the project is to map, prioritize and encourage protection of the remaining natural areas in the Huron River watershed. For this purpose, HRWC looked at properties larger than 10 acres, including forest, wetlands and grasslands. This type of land is sometimes referred to as a region’s “green” infrastructure,” she noted.

Olsson reviewed the list of benefits that natural areas provide to the watershed, including help in cooling and filtering runoff, providing a water supply, controlling erosion, managing stormwater and regulating climate. The Huron River is the cleanest urban river in southeast Michigan, she noted, and that’s because there’s still a fair amount of natural area in the watershed. “The more natural areas we have, the better,” Olsson said.

Over the years, watersheds in general have become more developed. As of 2000, 43% of the land in the Huron River watershed was open space, 26% was agricultural, and 31% was developed. But in the next 20 years, 40% of the remaining open space is expected to be developed, Olsson said. Master plans and zoning ordinances in most communities don’t designate space for natural areas, and almost all natural areas are in private ownership and designated for some other use, such as residential or commercial development. And because current trends favor low density, she said, that means development consumes a lot of space per person.

In the Huron River watershed, trends include fragmentation of natural areas, loss of wetlands, and the loss of particular kinds of natural features, including oak barrens, prairies and wooded wetlands. Those are the kinds of areas that HRWC is prioritizing for protection.

HRWC’s key messages, Olsson told commissioners, are: (1) encourage higher density development where infrastructure already exists; and (2) preserve natural areas so they can continue to provide the ecological services necessary to maintain quality of water, air, land, and life.

One purpose of the bioreserve project is to assess the remaining natural areas. Limited resources mean that not all natural areas can be protected, Olsson said, so a detailed inventory of the areas will help in determining which parcels should be preserved.

To do that, HRWC started with aerial photos in 2000, and used those to delineate areas that were forests, grasslands, wetlands – anything that could be defined as a natural area. The process used GIS (geographic information systems), and Olsson noted that GAC member Shannon Brines had been involved in this process. [Brines is manager of the Environmental Spacial Analysis (ESA) lab at the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources & Environment.]

The process determined that there were more than 1,700 sites mapped as potential natural areas. The entire watershed is about 994,000 acres, and of that about 247,000 acres are in the bioreserve. Using GIS data, these areas were ranked on 15 criteria, including total size, the size of the core area, topographic and geological diversity, and remnants of endangered “plant communities.”

Olsson noted that a lot of the criteria to prioritize the bioreserve are also used in prioritizing the greenbelt’s preservation efforts.

After HRWC created the GIS map, they started doing field assessments of some of these natural areas to get more information that will help conservancies and other programs – like Ann Arbor’s greenbelt – make decisions about which parcels to preserve. Olsson described the process of doing the assessments, which relies on trained volunteers. Information from that assessment – including a plant checklist, a description of invasive species and other details – is entered into a database, from which a report is generated. That report is then distributed to conservancies and other land preservation programs.

So far, HRWC has trained 249 volunteers and assessed 274 properties. Reports based on this data have helped preserve about 200 acres of land, Olsson said. Another five properties with a total of 547 acres are being evaluated now.

Olsson told commissioners that the HRWC hopes this data is used for “strategery” – helping land preservation programs make informed decisions about how to protect natural areas. Programs in Ann Arbor Township, Scio Township and Webster Township in particular have used the information, she said. [GAC member Jean Cares is also a member of the Webster Township farmland and open space board.]

Bioreserve Project: Commission Discussion

John Ramsburgh asked whether HRWC ever revisits the original bioreserve map. Kris Olsson replied that they’re looking at adding to the map – using historical photos to determine what land has not been plowed in the past. If it’s unplowed, there’s a strong chance that it will have a better seedbed.

In terms of updating the map’s boundaries, Olsson said it took a lot of work to do the original mapping, so an update would only likely occur if there were an automated way to do it.

Ramsburgh also asked for the source of the information that 40% of the remaining open space is expected to be developed in the next 20 years. Olsson said that came from the 2000 land use data generated by the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG).

Ramsburgh also wanted to know what relationships HRWC had developed at the University of Michigan. [Ramsburgh is a development officer with UM’s College of Literature, Science & the Arts. Commissioners Shannon Brines and Catherine Riseng also work for UM, and developer Peter Allen is an adjunct faculty member at UM's Ross School of Business.]

In addition to the GAC connections, Olsson mentioned naturalist Tony Reznicek, and Bob Grece, director of UM’s Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum, who was director of Olsson’s masters project.

Responding to another query from Ramsburgh, Olsson said that HRWC does offer internships, though there are none currently available for the bioreserve project.

Greenbelt Scoring Criteria

Dovetailing with the bioreserve presentation, Ginny Trocchio – who provides staff support for the greenbelt program – briefed commissioners on the screening and scoring criteria used to review potential greenbelt acquisitions, primarily through the purchase of development rights (PDR). [.pdf of scoring criteria]

There are two sets of criteria that differ only slightly – one for agricultural land, and another for open space/natural areas. Some properties are a mixture of both, but the predominant feature is chosen for scoring purposes, Trocchio said.

For both types of land, there are three major scoring categories:

- Land characteristics, such as soil type, parcel size and road frontage.

- Context, including how the land relates to adjacent or nearby properties.

- Acquisition considerations, such as whether there are matching funds available.

Trocchio reviewed details in each of these categories for both agricultural land and natural areas.

Archer Christian asked Trocchio who determined how each of these categories were weighted, and how that determination was made. Trocchio replied that she wasn’t involved in the program when the scoring mechanism was originally developed. Her understanding is that during the commission’s first year, they wanted to create the criteria before accepting applications. So the city hired a consultant to help develop that scoring mechanism. [The 30-year millage that supports the greenbelt program was passed by voters in 2003, and GAC was formed in 2004.]

Trocchio noted that at different points since then, some additional criteria have been added. For example, the criterion awarding points if a property is located within an agricultural preservation district was added after the original criteria were developed. When the greenbelt program began, most townships didn’t have this kind of district, Trocchio explained. At one point, the state considered creating a purchase-of-development-rights (PDR) program. One criteria to be eligible for state grants would have been that townships have an area designated as an agricultural preservation district. Even though the state PDR program didn’t materialize, most township master plans have been updated to include those districts, Trocchio said.

Christian wondered if the original members of the greenbelt advisory commission expected that the scoring would be revisited at any point. Trocchio said she didn’t know. [No original members of GAC remain on the commission. The last two original members – Dan Ezekiel and Laura Rubin – were term limited and cycled off the commission in 2013.]

Trocchio highlighted other criteria. Some examples of characteristics that result in higher scores for property include:

- Has 3-4 natural features (stream corridors, woodlots or rare species).

- Located within 1 mile of the Ann Arbor city limits.

- Located within a township or village that has passed a purchase-of-development-rights (PDR) ordinance.

- 90% or more of the property’s perimeter is open space.

- Located adjacent to more than one protected property.

- Provides “broad, sweeping view from publicly accessible sites,” or has unique or historical features.

- Contains a Huron River tributary or is located along the river.

- Has 3 or more possible sources of matching funds.

- Landowner is willing to contribute 20% or more of the appraised value of development rights.

Most of the applications to the greenbelt program receive between 40-60% of the possible points, Trocchio said. Several recent applications have scored higher, mainly because of points awarded for being adjacent to protected land. That’s because more land is protected now than when the program first started, she noted.

Trocchio concluded by noting that information about this scoring system is on the greenbelt program’s website.

Staff Report

Ginny Trocchio also gave a brief staff report during the Feb. 6 meeting.

Ginny Trocchio of The Conservation Fund, who provides staff support to the city’s greenbelt program.

She reported that Congress finally passed a farm bill, that was due to be signed by President Barack Obama the following day in East Lansing.

As anticipated, the bill combined different conservation easement programs into one program, she said. That includes the farm & ranchland protection program (FRPP), the grassland reserve program and the wetland reserve program. [The city's greenbelt program has received millions of dollars in FRPP matching funds over the past decade.]

In terms of continued funding, it’s expected to be fairly high for the next five years, Trocchio said – between $400 million to $500 million annually through 2017. It’s a good thing for the greenbelt program that there will be federal funding available, she said.

Trocchio reported that work is moving forward on the greenbelt’s new registry program. A brochure was designed and is being printed. A one-page agreement letter for landowners to sign has been vetted by the city attorney’s office. She said she’ll be working with commissioners Catherine Riseng and Shannon Brines – GAC’s chair and vice chair, respectively – to develop a summary of the registry program to send to city council as an information item.

By way of background, the registry was part of an updated strategic plan that the commission approved at its April 4, 2013 meeting. From the updated strategic plan:

In addition, recognizing that over the next 3-5 years, the Greenbelt will likely shift in program focus and will not be able to acquire as many properties or easements annually, it is important that the Commission maintain contact with landowners in the Greenbelt District who may be interested in protecting their land in the future. Therefore, the Greenbelt will prioritize establishing a Greenbelt Registry Program.

A land registry program is a listing of the properties that contain “special” natural features or has remained in farmland open space that landowners have voluntarily agreed to protect. This is an oral non-binding agreement between the City of Ann Arbor and the landowner. The landowner can end at any time, and the agreement does not affect the deed. The landowners agree to monitor and protect specific features of the property and notify the City if the landowner is planning on selling the property or if major threats have occurred.

The purpose of the land registry is to identify significant parcels of land and, through voluntary agreements with landowners, take the first step toward protection of the land’s natural resources. Furthermore, a land registry program recognizes landowners for protecting significant open space/natural features. Ultimately, these lands could be protected permanently through a conservation easement.

The landowner, by voluntarily agreeing to register their land, agrees to the following:

- Protect the land to the best of their ability

- Notify the City of Ann Arbor Greenbelt Staff of any significant changes they are planning or any natural changes that have occurred.

- Notify the City of Ann Arbor Greenbelt Staff of any intent to sell the property.

Land Acquisition

Most meetings of the greenbelt advisory commission include a closed session to discuss possible land acquisitions. The topic of land acquisition is one allowed as an exemption by the Michigan Open Meetings Act for a closed session. On Feb. 6, commissioners met in a closed session that lasted about 30 minutes. There was no action item when they emerged, and the meeting was adjourned.

Next meeting: Thursday, March 6, 2014 at 4:30 p.m. in the second-floor council chambers at city hall, 301 E. Huron. [Check Chronicle event listings to confirm date] The meetings are open to the public and include two opportunities for public commentary.

Present: Shannon Brines, Jean Cares, Archer Christian, Jennifer Fike, John Ramsburgh, Catherine Riseng, Christopher Taylor. Staff: Ginny Trocchio.

Absent: Peter Allen, Stephanie Buttrey.

The Chronicle survives in part through regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of publicly-funded entities like the city’s greenbelt program. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.