Archives: Starting Off on the Wrong Track

Editor’s note: Calamities like the recent Sendai earthquake impose tragedy on a grand human scale. History will undoubtedly document countless individual acts of heroism and bravery amid that tragedy – ours is not a completely cowardly species. It takes a different sort of bravery simply to deal with the result of a private tragedy of your own making – just by trudging forward with your life the best you can. This week local history columnist Laura Bien looks back on a tragedy like that – caused by a poor personal choice of a pedestrian path.

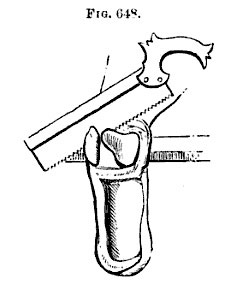

The likely method by which Josef's feet were removed, from Gant's 1886 "The Science and Practice of Surgery."

Josef Panek walked north along the twin railroad tracks leading to the railyard at Depot Town. He was a slender man about 40 years old, dressed in work clothes and a cap and carrying a tin lunchpail. He was headed towards the Ypsilanti Paper Mill.

Thank goodness his brother at the mill had gotten him a job. Josef’s wife Anna was caring for four children, including the newborn Mayme, in their tiny apartment on Michigan Avenue. And after the 12-day trip over the Atlantic three months earlier in April of 1880 on the steamship Baltimore, their savings were gone. But what a thrill it had been to finally see the New York skyline. Despite his and Anna’s lack of English, he had managed to maneuver the family through the city’s bustle and clangor and continue overland and over water to Detroit and finally Ypsilanti.

The job at the mill wasn’t too bad. His brother had helped translate the foreman’s instructions, and the machinery wasn’t too complicated, though the work was tiring.

Josef entered the Depot Town railyard, where the twin rail lines fanned out into numerous tracks. He’d been lucky to find work, and this strange place shared a few things with Czechoslovakia after all. Josef glanced over at the greenery along the river. Even some of the trees were the same, and a couple were just beginning to turn color, just like home.

Ahead lay the Forest Avenue railroad bridge, where the track turned left and vanished behind riverside foliage. Abruptly a whistle shrieked and a train appeared. It was on Josef’s track. Josef scrambled to the next track, away from the approaching thudding and clanging. Possibly someone yelled a warning, in a language Josef didn’t know. He never heard, from the opposite direction, the other train.

He screamed, caught under the enormous wheels.

Nearby workers sent for Dr. Batwell and ran to gather around Josef. He was still alive, but his feet made for a sight that was hard to behold. Josef had to be moved from the tracks. Several men lifted him and carried him away from the rails. His feet dangled like limp red socks.

It was no sight for the ladies and other passengers waiting at the Depot. Perhaps Josef was taken to the freighthouse on the other side of the tracks and laid down to await Dr. Batwell. Josef was losing blood.

This family photo shows Frank Panek, baby Louise, Frank Jr. and his brother Edward, Josef Panek, Viola, and standing are Stasia and Mayme. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Dr. Batwell arrived within half an hour, and saw that things were dire. Should Josef be moved by wagon to Batwell’s office at 13 South Huron, across town?

It may be that Dr. Batwell performed the double amputation in the freighthouse, as Josef sweated and screamed on an operating table made of packing crates.

If so, it’s possible that the sanitary conditions amongst the freight weren’t much worse than in Dr. Batwell’s office, given the state of the medical art. Beginning in 1867, English doctor Joseph Lister, inspired by the work of Louis Pasteur, had published his findings on the importance of antiseptic conditions in surgery.

The laurels Lister won for his work included a Lordship, the honorific naming of Listerine, and his very own eponymous food-borne pathogen, listeria. However, at the time of Josef’s accident in 1880, American doctors were divided on the worth of Lister’s methods. Many doctors rejected them. Acceptance of Lister’s practices among American doctors would take another two decades.

The shock of Josef’s double amputation and the era’s variable observance of sanitary procedures made Josef’s prognosis poor. The September 25, 1884 issue of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal summarized the results of 123 amputations performed at the Rhode Island Hospital between 1868 to 1885. The report noted that the vast majority of injuries resulted from accidents with trains or machinery.

One table summarized the results of leg amputations between 1871 and 1881, noting that the hospital adopted what was popularly called “Listerism” in 1878. Of the nine amputations before the adoption of antiseptic procedures, seven patients died. Of the seven amputations done after the adoption of antiseptic procedures, only one died.

Another table noted the prognoses of the four patients who between 1878 and 1880 had foot amputations similar to Josef’s. Even though all had occurred after the hospital’s adoption of Listerism, two had died.

Josef’s accident was reported in the September 9, 1880 Ypsilanti Commercial. After a sympathetic recounting of the accident, the paper said, “His family is destitute, and demands municipal and private charity.”

In an age without federal welfare or social security plans, Ypsilanti, like other communities, relied on ad hoc local charity for its less fortunate. The leading charity organization was the Ladies’ Aid Society, a group of some of the town’s most socially prominent women who raised and distributed funds to causes they judged worthy. Their account book records for the years of 1880 and 1881 show expenditures to pay the rent of “old man Zorn,” to buy medicine for Mrs. Dalyrimple, to mend shoes for Mrs. Everetts, and to buy firewood for Mr. Young. There is no record of aid given the Paneks.

By 1900, Josef’s wife Anna would lose two of her five children, a possible hint of extreme financial hardship.

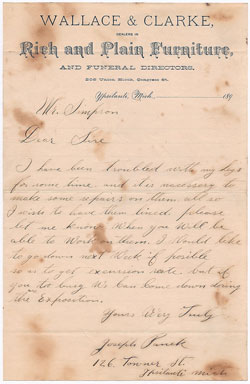

But Josef survived the operation. His legs, which now ended in smooth stubs at the ankle, were fitted with prosthetic feet. They didn’t fit very well and caused Josef pain. Judging by its incomplete date and the mention of an Exposition [likely the annual Detroit Exposition, which began in 1889], it was probably sometime in the 1890s when Josef dictated a letter to one Mr. Simpson.

This was probably Detroit artificial leg maker William Thomas Simpson, the well-known improver and champion of the famed “Foster Limb,” and arguably the most lauded artificial leg-maker in Detroit history. Josef said:

Dear Sire,

I have been troubled with my legs for some time and it is necessary to make some repairs on them. All so I wish to have them lined. Please let me know When you Will be able to Work on them. I Would like to go down next Week if possible so as to get excursion rate [on the train]. But if you are too busy We Can Come down doring the Exposition.

Yours Very Truly,

Joseph Panek

Despite the discomfort, Josef retained his job at the paper mill. The family was eventually able to buy two adjacent plots of land on Towner street, off Prospect near Michigan Avenue.

Josef dictated a letter to Detroit artificial-leg kingpin William Simpson. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Josef lived on one lot, and his son Frank, who worked as a furniture upholsterer and had started his own family, lived on another.

By 1910, Josef had retired and was a widower. He lived with his 32-year-old son Vincent, a butcher, and his 28-year-old single daughter Mayme, who would later become famous in town for her award-winning gardens. Frank’s son Frank Jr. would become a well-known local musician and theater orchestra director.

Josef died just after the World War at age 78 or 79. Fate had struck him down soon after his venture to a new world.

He’d been crippled, impoverished, and apparently never had learned to read or write English.

Yet he had persisted, and had seen his surviving children gain a measure of comfort, stability, and community standing.

He is buried, likely with his prosthetic feet from the accident nearly four decades earlier, in Ypsilanti’s St. John’s Cemetery.

Mystery Artifact

Last week’s mystery artifact was from the wonderful book “Handy Farm Devices and How to Make Them” by Rolfe Cobleigh – a must-have book for any DIY-er. It was first published in 1909 but there are modern editions available – still in print over a century later!

The section pertaining to this device reads, “Here is a way of making play of wash day. Perhaps some of our bright boys will try this to help mother.” Yes, it’s a bike-powered washing machine. The little wheel over the back emery wheel is just an emery wheel the inventor threw in for good measure. Exercise, laundry, and knife-sharpening, all in one!

Cmadler, abc, and Irene Hieber guessed correctly.

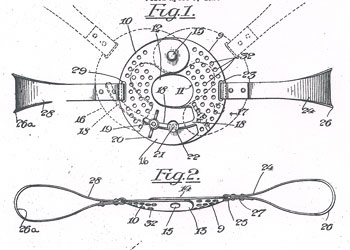

This column we’re venturing into a device that somehow relates to this week’s story from the archives. In the top drawing, you can see via the faint lines how this item opens like a pair of pliers, then closes to make perforated metal ring. Odd thing. What might it be? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and the upcoming book “Hidden Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

“…that somehow relates to this week’s story…”???

Really! Oh my god, you don’t want my guesses. Please go away David Cronenberg.

Heh. Well, abc, of course there are several little tangents here that are also part of the story…antisepsis versus anti-antisepsis advocates, private charity organizations, Louis Pasteur for a minute there, Detroit prosthesis kingpins, &c. :)

OK so where do pliers with a hole the size of… say a bone, fit in? Oh and by the way those pliers are perforated so that they won’t hold fluids. What’s that about?

I suspect that this device is accompanied by a leather biting strap.

Or maybe its an after the fact piece; something to protect the limb post operation. Like a shoe.

I am still not enjoying this.

Ditto what ABC said. I’m guessing it’s a device to cut away tissue before the bone would be sawed.

If Josef Panek arrived in 1880, he could not have come from Czechoslovakia. That country did not exist until 1918, when it was formed from a portion of Austria-Hungary.

You are correct. The country of origin on his immigration documents and in the census indicates “Bohemia.” I modernized it to make it clearer, but I probably should have included a parenthetical explanation; good feedback that I”ll remember for the future; thank you, George.

Although originally a medical instrument, by Panek’s time surgeons used these to brew coffee during long operations. You close it around the percolator tube, tamp the grounds down on the perforations, and turn up the alcohol burner. Spent grounds would be disposed of in the nearest bedpan.

I wonder if there are any descendants of Joseph Panek or his son in the Ypsilanti or Ann Arbor area. I think they would be proud of Joseph. Thank you for a great article!

Jim Rees: For some of the operations described in some of the old 19th-century surgery books, you’d think the doctors might need a beverage with a bit more kick than caffeine to get through it. But your guess is noted.

Roadsidedinerlover: There are a few Paneks in the area. But I’m not sure if it’s the same family: a LOT of people with this surname appear to have immigrated. There were many Paneks who settled in Detroit as well, including one Detroit Joseph Panek which threw me for a while till it got sorted out.