In the Archives: Women’s Underwear

Editor’s note: The Chronicle winds up March, which is Women’s History Month, with a column from publisher Mary Morgan about Jean Ledwith King, and Laura Bien’s regular local history column, which takes a look at women’s underwear.

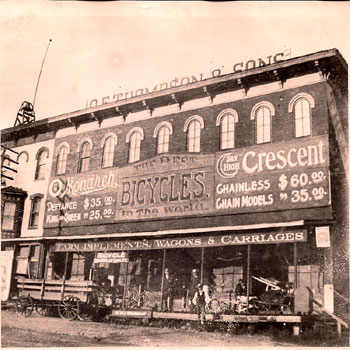

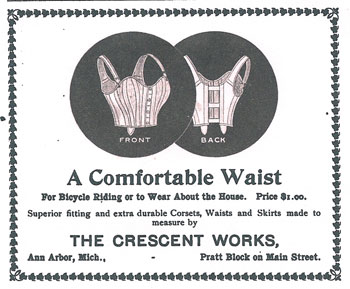

In 1894, Ann Arbor's Crescent Clasp Works at 39-41 North Main employed 13 women making corsets, waists, and hosiery. They included machine operators Clara and Lillie Scheffold, Minnie and Anna Schneider, Emma Tenfel, Kate Saunders, Eugenia Gauss, Ida Kuebler, Lilly Biermann, Ida Oesterlin, Dora Walz, Jennie Jacobus, and Anna Kuster, plus stenographers Clara Markham and Mary Pollock.

This time last year, census canvassers were going door-to-door, asking their 10 questions about each home’s residents, their individual sex, race, and age, and whether the property was mortgaged.

Imagine if they’d asked each woman about her style of underwear.

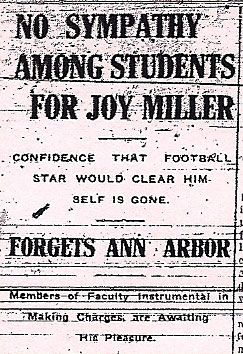

Thirteen thousand women were asked that question in 1892 by Michigan state officials.

The officials were male, but oddly enough it was women who were responsible for inserting the undergarment question into the state-funded survey.

The winding road to this naughty quiz began with an 1880s state governor who was concerned about the working class. [Full Story]