Column: Singin’ the Ann Arbor Blues

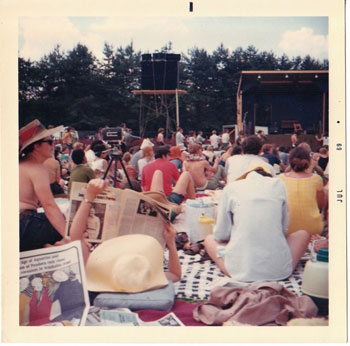

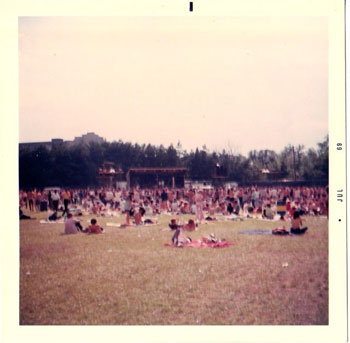

The crowd at Fuller Flatlands, site of the first Ann Arbor Blues Festival 40 years ago. (Photo courtesy of Bob Frank, www.bluelunch.com.)

Forty years ago this month, a great crowd of young people converged on a small, unsuspecting middle-American town for an incredible three-day celebration of peace and music. They sat on the cool grass of an open field, grooved to the tunes of a dizzying array of legendary performers, smoked pot, drank wine, and generally had a blast. It was a landmark event that is still spoken of in hushed tones of awe and reverence among music historians.

No, it wasn’t Woodstock. It was something similar, yet very different, something smaller yet in some ways bigger.

It was something called the Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

In early August 1969, two weeks before the mammoth fete in Bethel, N.Y., approximately 20,000 eager spectators came to the Fuller Flatlands on the banks of the lazy Huron River to hear an absolutely astounding lineup of living legends of the blues – B. B. King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Rush, Magic Sam, Big Mama Thornton, Son House, T-Bone Walker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and on and on – at the first major blues festival in the United States.

Although the Ann Arbor event has been almost completely overshadowed by its big brother in New York, to many serious music fans – especially blues enthusiasts – it is by far the more important of the two. Writing in the October 1969 issue of Downbeat, critic Dan Morgenstern made his preference plain, dismissing Woodstock in favor of the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, which he declared was “without doubt the festival of the year, if not the decade.”

Choosing the Blues

But it wasn’t just the cultured music critics for whom the choice was clear. In the spring of ’69, Steve Wanvig was a 19-year-old blues fan living in Minneapolis. “I was working at an aluminum window and siding company,” he says, “when I heard about this massive rock show which was to take place in the summer, out in upstate New York.”

“I wanted to go,” remembers Wanvig, “but I was much more interested in the massive blues show which was to take place in Ann Arbor, Michigan, much closer. So I enlisted a high school buddy to drive his red ’67 Chevy Impala over there. Jim V (may he rest in peace) wasn’t even a big blues guy, but he was a good enough friend to provide transportation. We threw a tent and some sleeping bags in the car and headed east.”

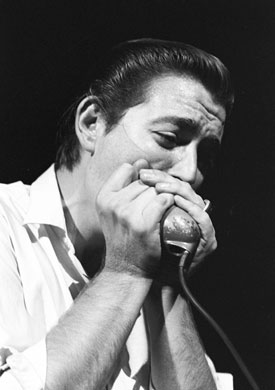

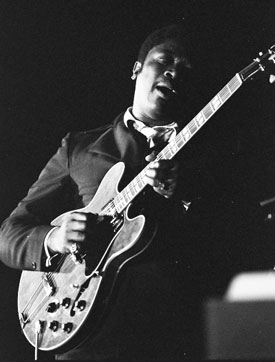

Charlie Musselwhite performing at the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

At that time Wanvig was particularly enamored of the magic harp (blues-speak for harmonica) of Charlie Musselwhite. “Musselwhite was to play in Ann Arbor; that did it for me,” says Wanvig, now an artist and graphic designer. “But besides him, you had the biggest collection of blues legends ever to perform on one stage. It was an absolute, stone-cold MUST for anyone who called themselves a blues fan. I chose the blues, and I’m glad I did.”

While Woodstock was remarkable largely because of the sheer size of its audience, the Ann Arbor Blues Festival was all about the music. “This particular happening did not attract even one-tenth of the 300,000-plus that Woodstock could boast,” wrote Dan Morgenstern in Downbeat. “Total attendance for the three evening and two afternoon concerts at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival was around 20,000. But everyone there had come to hear the music – not to make the scene – and the enthusiastic response was a joy to behold.”

Baby Boomer Blues

Most writers who attended the festival remarked upon the enthusiasm of the audience. Many also noted the striking contrast between the performers on the stage – mostly older, impecunious black men, with roots in the Deep South –and the spectators on the field, who were mostly young, white, and well-off. “It was an odd sight to see white youngsters besieging black men in their sixties and seventies for autographs,” wrote Hollie West in The Washington Post.

In hindsight, however, it shouldn’t have seemed all that odd. Throughout the 1960s there had been occurring what has been termed a “blues revival” – although that is something of a misnomer, since the blues had never actually died. Instead the phenomenon would be more accurately described as an awakening of interest in the blues in an audience that previously hadn’t paid it much attention – young, white, educated Americans.

The blues had first started to appear on the radar of the boomer college crowd in the early sixties, as part of the folk music explosion. A few African-American country bluesmen were booked into the coffee houses and were admired by audiences as purveyors of a truly “authentic” form of traditional American roots music. A number of popular white folkies, such as Bob Dylan and Dave Van Ronk, also included blues material in their repertoire.

The rise of interest in acoustic blues was followed by a surge of enthusiasm for the heavily blues-influenced rock ’n’ roll of the early British Invasion. The Rolling Stones, the Animals, the Who, and the Kinks were among the many English rock bands that – ironically enough – introduced scores of young American listeners to the blues, via rocking covers of blues standards as well as their own blues-tinged originals.

By the late sixties a new white blues-rock scene was in full swing on both sides of the Atlantic. Janis Joplin, Paul Butterfield, Canned Heat, Steve Miller, Fleetwood Mac, Eric Clapton, and others made millions with their hybridized versions of black American blues. At the same time, most freely acknowledged the debt owed their African-American forbears, who in turn enjoyed an increase of interest in their work (although nothing on the level of the white performers).

Roots of the Festival

The Ann Arbor Blues Festival was the brainchild of a small group of University of Michigan undergraduates, led by John Fishel, a 20-year-old anthropology major. Music festivals had become quite fashionable in the late sixties, and Fishel remembers that there was interest on campus in putting together some sort of fete.

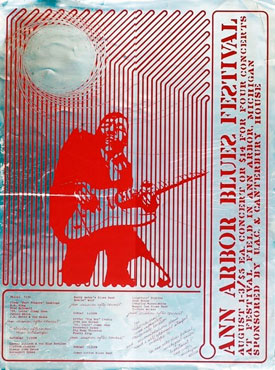

Promotional poster for the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival. (Photo courtesy of Michael Erlewine, www.michaelerlewine.com.)

“Somebody put me in touch with one or two people,” he says. “It ended up with maybe four or five of us getting together. Some of us knew each other, some didn’t. We really didn’t have a concept at the time. We didn’t know whether it would be a series or a one-shot deal. We didn’t know whether it was an inside show in an auditorium, or whether it was an outdoor show. But I agreed to do the entertainment part of it.”

Having been a blues enthusiast from an early age, Fishel naturally wanted to make it a blues festival. The others were either of like mind or were easily persuaded, and so, nascent concept in hand, they set about putting the gears in motion. Fishel and several companions traveled to Chicago, then probably the biggest blues city in America, to make key contacts among the performers and promoters, and to get a better feel for the milieu.

Fishel put his knowledge of the genre to work, and expanded his horizons in the process. “I had a lot of records at the time and I had some sense of who was alive, who was still performing. But there was much more that I didn’t know and it sort of took me into a world that I remain very fortunate to have had the opportunity to be part of.”

Easy Money

Probably the most crucial part of the festival’s development was fundraising. In that the organizers were unbelievably fortunate. Somehow they persuaded two university-connected nonprofit entities – the University Activities Center (UAC), and Canterbury House, the student Episcopalian organization – to put up $70,000 for the event. (That’s a jaw-dropping $400,000 in today’s money.) “To this day, I’m still not clear why they said yes,” marvels Fishel.

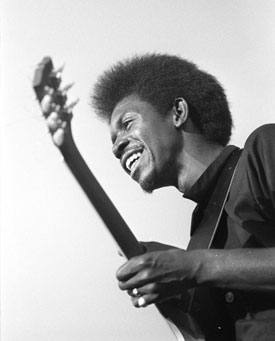

Cash in hand, the small group of organizers began to develop the festival in earnest. It was decided to hold a try-out of sorts – a small, free blues concert – in the spring of 1969 in order to gauge potential interest. On one of their trips to Chicago they had discovered the perfect artist for such an event: the then-unknown guitarist Luther Allison.

“We sort of discovered Luther Allison,” says Joel Silvers, another of the festival’s organizers. “He was playing in this very traditional West Side club where most of the people were fresh from the South. I don’t know who initiated the conversation with him, but he was absolutely delighted to find any interest whatsoever in a university or a white audience for the kind of music that he was performing.”

Allison came to Ann Arbor in late April for a four-hour free show in the ballroom of the student union. At first the audience was small. But, as John Fishel remembers, “he started to play, and it was electric. People just started to pour in from all over the campus.”

As the performance wrapped around midnight, the planning committee were all smiles. The blues had passed the test; the community had responded. The show would go on.

Radical Blues

Today many may wonder why Ann Arbor – a small, Midwestern town, far from the South, with a tiny black population – should have been the site for the country’s first major blues festival. But consider that the core of the white awakening to the blues in the 1960s were the free thinkers, political activists, and countercultural rebels – and that in those days Ann Arbor was a major center of anti-establishment activity, home to all those types and more.

Festival organizer Bert Stratton recalls that in those days to like the blues was to be part of an exclusive, rebellious club. “It was like a secret language. If you were a young white kid who was into the black blues you thought you were pretty cool. It was an identity search on our part. We wanted something that was totally authentic, as opposed to what we were, which was not, I guess,” Stratton says with a chuckle. He explains that listening to performers like Howlin’ Wolf or Muddy Waters was a sure-fire way to annoy the “straights.”

Joel Silvers remembers that in the sixties there was a politicized subculture that followed American roots music. “A lot of these people were white,” he says, “but had their roots in the civil rights movement. These were people who were both counterculture and highly politicized in some way or another. I mean they were still college students. They weren’t necessarily marching in Selma, but they were absorbing this sense of a black-white cultural alliance that was still possible in 1969.”

“Within a couple of years,” he adds, “between black power and whatever happened in terms of a cultural backlash or political backlash, a lot of white kids were no longer as interested in authentic black music, so it was a bit of a short-lived phenomenon.”

Part of the radical agenda in the late sixties was a rejection of mainstream white culture in favor of that of minority groups, especially African-Americans. From early on the festival organizers had decided that it would feature predominantly black performers. This decision was made not only to help right the wrongs that black artists had been suffering for decades, but also to expose concertgoers to the roots of the blues, with which many were expected to be unfamiliar. Festival organizer Cary Gordon told The Washington Post, “I feel the blues is a black phenomenon, and assuming there will be more blues festivals after this, we felt the first festival here should be devoted to first-generation blues.”

Bert Stratton remembers that at the ’69 festival it was unofficially decided that black attendees would be let in without charge. Not that it much mattered, he says. “I don’t think we had more than 50 black people in the audience at any one time.” He also suspects that although their hearts were in the right place, the organizers were unwittingly insulting those they intended to help. “It would have been totally embarrassing for any black person to say, ‘I want to get in for free,’” he says.

“This Is So Beautiful”

The first Ann Arbor Blues Festival got underway at 7:30 p.m. on Friday, August 1, 1969. Over the next two days attendees would be treated to nearly 24 solid hours of the best and most authentic blues music the country had to offer, old and new, from country blues to city blues and everything in between. Some reviewers had minor complaints about one or two of the performances, but overall critical opinion was glowing. Norman Gibson of The Ann Arbor News perhaps summed it up best, writing simply that “the first Ann Arbor Blues Festival in history was a success from almost any point of view and those who arranged it can be proud of the results.”

The audience was, if anything, even more enthusiastic than the experts. Many performers received heartfelt standing ovations, and the moving, quiet performance by the venerable Son House that closed the festival brought tears to the eyes of many. Dan Morgenstern wrote in Downbeat that “the performers – especially the veterans – were treated with respect that bordered on reverence. It added up to a kind of recognition that blues artists have seldom, if ever, received from their own people.”

For their part the performers were more than happy to bask in the unaccustomed glow of appreciation that the festival audience gave. To many it was the most amazing thing in which they had ever taken part. Michael Erlewine, a guitarist who played in a local blues band, helped out behind the scenes at the festival and had a chance to interview many of the performers. He recalls that James Cotton told him, “I’ve never seen nothin’ like this in my life. This is the beautifulest thing I ever seen in my life. This is so beautiful.”

Festival organizer Ken Whipple related a similar story to The Michigan Daily, about how he met B. B. King coming off the stage after finishing his set. “He put his arm around me,” Whipple said, “asked me my name and said what a great thing it was that he was able to be here. There were tears in his eyes. It’s the greatest thing in the world.”

It was also a sad fact that most of the performers were thrilled with the money. “The Blues Festival is a dream for some of these guys, not for the prestige but because they need the bread,” John Fishel told The Michigan Daily. “These guys will play two nights a week from 8 until 5 in the morning and only get $30. And even if they do get a chance to make a record, they usually get screwed.”

One of the more significant aspects of the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, in the opinion of music promoter Dick Waterman, was that it was the first to pay black bluesmen a commercial wage. “Others such as Newport, Berkeley, UCLA, Mariposa, et. al., insist on $50-a-day-plus-travel,” wrote Waterman in 1969, “which is fine for an act that is making a regular living – Baez, Dylan, Peter, Paul and Mary – but hard on the bluesman who needs the festival for exposure but also needs it for actual living money.”

In this the Ann Arbor event served as an example to other music festivals, for even though the dozens of performers were paid a commercial wage, the first Ann Arbor Blues Festival not only recouped its original $70,000 investment, when all was said and done it had made a profit of about $200.

Ann Arbor Blues Part Deux

Following the unprecedented success of the first Ann Arbor Blues Festival, there was no question that there would be a second. There was a new group of organizers (including a few of the originals such as John Fishel), but they planned the second festival to be much the same as the first, on a slightly larger scale, given the bigger budget that was allotted by UAC and Canterbury House, who once again were sponsoring.

The success of the first festival brought more attention from the media for the second. The 1970 Ann Arbor Blues Festival was another astounding artistic success, a joyous experience for audience and performers alike that earned the raves of critics from Downbeat, Rolling Stone, Billboard, and newspapers across the country.

Financially, however, it was a disaster.

As early as Sunday afternoon, festival organizers realized that they were going to post a loss of nearly $20,000, an amount that would be ruinous to the sponsors.

The second festival appears to have suffered much more than the first at the hands of gate-crashers. It also had the bad luck of taking place the very same weekend as a giant rock festival near Jackson, at a park called Goose Lake. That event boasted an impressive roster of popular acts, including Chicago, Rod Stewart, Bob Seger, John Sebastian, and Jethro Tull, and would draw an estimated 200,000 attendees over three days. The Goose Lake Festival is an intriguing story in its own right – barbed wire, sanitation problems, emergency food deliveries, overzealous security, drugs being sold openly like concessions – but in relation to the Ann Arbor Blues Festival it is usually cast as the grinch who stole Christmas.

Undoubtedly, Goose Lake did have a negative impact on attendance at the Ann Arbor event. But in fact the figures seem to show that attendance at the second festival was roughly the same as the first. What must also be considered is that organizers spent more money on the second festival, and at the same time lowered ticket prices by almost 30%. This was done in hopes of attracting more attendees, but in hindsight may have been a critical mistake.

Moreover, the overwhelming success of the first festival, with its lineup of performers who were virtually unknown outside the world of blues freaks, may have led the planners to be a bit overconfident. Two weeks before the festival, The Washington Post reported that tickets would be limited to 15,000 “because festival organizers want to emphasize the music and not the event as a happening.” The Post quoted one of the organizers as saying – somewhat ominously, in light of what would happen – that they were trying to make the event “as esoteric as possible.”

This was perhaps not the wisest course of action, especially with so much money on the line.

Whatever the reason, however, the damage had been done, and the future of the festival was in peril. In hopes of making up the loss, and saving UAC and Canterbury House, festival organizers put out a plea for donations. They also turned to some high-profile blues-rockers for help. John Fishel explains:

“Johnny Winter came in 1970 as a guest, appeared back stage, hanging out. He then went on stage with Luther Allison, and they played together, to the delight of the audience. When the festival lost money, we went back to him and asked him if he would do a benefit.” Winter readily agreed, and played at the University of Michigan’s Crisler Arena a week later, along with some of the other performers from the festival. Fishel recalls that enough money was raised to make good the loss.

Fishel also remembers a tantalizing might-have-been. “We were also trying to get the Rolling Stones to come and we got pretty close. Their schedule didn’t allow them to do a benefit. Maybe if they had been there we would have raised sufficient money to not only pay the debt off, but also to continue the thing in ’71 and it might have been a different reality.”

As it was, despite the repayment of the loss, the university was not about to risk another such financial calamity, and the request for a third festival in 1971 was turned down. It seemed that the brilliant light that had shown on the blues in Ann Arbor the two previous years had been snuffed out.

Rainbows to the Rescue

All was not lost, however. John Sinclair was a hippie activist living in Ann Arbor who had come to national attention when in 1969 he was sent to prison for 10 years for giving two joints to an undercover policewoman. His unusually harsh sentencing became a cause célèbre, attracting such notables as Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Allen Ginsberg, Jane Fonda, and John Lennon. The two-year campaign to free him culminated in a huge rally at the University of Michigan’s Crisler Arena, at which Lennon, Bob Seger, Stevie Wonder and others performed.

Released from prison shortly thereafter, Sinclair was looking to get back into the fray, but perhaps in a less controversial way. In 1968 he had co-founded the White Panther Party, which was modeled on the Black Panthers, and adopted that group’s highly confrontational stance toward the mainstream American establishment – including, ironically enough, the condemnation of white culture espoused by the Black Panthers.

While Sinclair had been in prison, however, the White Panthers had softened their tone, and changed their name to the Rainbow People’s Party, reflecting a new outlook that promoted peace and brotherhood. Sinclair had been a fan of black music since early childhood, and reviving the artistically successful Ann Arbor Blues Festival seemed like a perfect project for the freshly-minted Rainbows.

So Sinclair joined forces with local music promoter Peter Andrews to form a company unconnected with the university, Rainbow Multi-Media, and put on a new festival. But this time around there would be no talk of being esoteric. Jazz, soul, and blues-rock were added to the bill, in hopes of attracting a wider audience, and bigger-name acts were booked, such as Ray Charles, Count Basie, Miles Davis, James Brown, Dr. John, Bonnie Raitt, and Booker T. & the M.G.’s.

The revamped Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival would run for three years, starting in 1972. Despite the changes instituted by Sinclair and Andrews, the new festivals would follow much the same course as the original two: each would be hailed as an artistic triumph, but financially would flop. After the disastrous 1974 festival, which had to be moved to Canada at the last minute because the newly-Republican Ann Arbor City Council refused to grant a permit, Sinclair called it quits. Once again it seemed that the light had gone out.

Ann Arbor Blues Redux

Peter Andrews had not given up, however. He kept the artistic ideals of the festival burning and in 1992 the Ann Arbor City Council was once again persuaded (without much difficulty: the vote was unanimous) to grant a permit for a revitalized Blues and Jazz Festival.

This time the festival would have its longest continuous run, surviving for nearly a decade and a half. But once again the familiar pattern would emerge: artistic success, financial failure. After the last festival in 2006 an accumulated debt of nearly $60,000 remained on the books.

The festival is now on what seems to be permanent hiatus. Peter Andrews is pessimistic about the possibility of another revival. There are too many blues and jazz festivals today, and to compete would require headliners that would make it nearly impossible to make money – a far cry from 1969, when Ann Arbor was host to the first major blues festival in history, and obscure but talented artists could draw a crowd.

Legacy

Although the Ann Arbor blues are no longer being sung, the festivals have left a rich legacy of which all can be rightfully proud. Especially the first two events, which brought together a lineup of blues maestros that had never been seen before – or will ever be seen again. The fact that the organizers were barely old enough to vote makes it all the more amazing.

John Fishel reflects on those early days with a mixture of pride and nostalgia. “I think the Ann Arbor Blues Festival did many things. It inspired the many blues festivals that came after. It resulted in a group of people who were primarily from Chicago creating a magazine, Living Blues, the first American magazine that was devoted to this type of music, a magazine that really became sort of the gold standard for those that were into it.”

“A number of labels were created as a result of the festival,” he continues, “people who came and got inspired because they heard people that they hadn’t heard before and went into the business, somebody like Bruce Iglauer, who created Alligator Records. It was a catalyst, which is wonderful.”

After a pause, he says simply, “It was magic.”

Alan Glenn is currently at work a documentary film about Ann Arbor in the sixties. Visit the film’s website for more information. While there you can contribute your memories of that time – and read those that others have contributed – in a public forum set up expressly for that purpose.

The best music I’ve ever heard and seen, ever, was at the Blues and Jazz fests in the 70′s.

Another great article capturing the zeitgeist of 60s Ann Arbor. Good luck with the doc.

A number of people have requested the lineup of artists who played the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

Friday Night, 8/1/1969

Roosevelt Sykes

Fred McDowell

J.B. Hutto and the Hawks

Jimmy Dawkins

Junior Wells

B. B. King

Saturday Night

Sleepy John Estes

Luther Allison

Clifton Chenier

Otis Rush

Howlin’ Wolf

Muddy Waters

Sunday Afternoon

Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup

Jimmy “Fast Fingers” Dawkins

Roosevelt Sykes

Luther Allison & the Blue Nebulae

Big Joe Williams

Magic Sam

Big Mama Thornton

Freddy King

Sunday Night

Sam Lay

T-Bone Walker

Son House

Charlie Musselwhite with Freddy Roulette

Lightnin’ Hopkins

James Cotton

A fantastic job, Alan. I was very happy to participate. Your wonderfully thorough and interesting article really brought back some memories. As I told you, about the only memento I have left from Ann Arbor ’69 is an 8 x 10 print I shot of Charlie Musselwhite. It’s good that he is still around, forty years on, to keep the blues alive. Articles like yours do the same! Thanks so much, and good luck on your documentary!

It is with great appreciation that I read this article. As a recent high school graduate in 1969, I traveled with my brother John Fishel into the clubs of Chicago’s West and South sides. This was purely work as fans of a music that we knew would gather steam and create a lasting impression on the music world. In fact, because of people like Bob Koester and Dick Waterman–who counseled my brother–the blues is still going strong 40 years later. Although most of the artists are now in Blues Heaven, I am proud to announce that my friends and I taped the festival on a very rudimentary noreleco recorder and the tapes have now been restored by my son and his co-workers at Columbia University’s WKCR. Nearly finished, the station hopes to have them on-air in the next month for a series of special presentations; and the great Ann Arbor photographer Stanley Livingston (in association with Michael Erlewine) has a photo book that will be released by year’s end on the University of Michigan Press. I am proud of my brother and all of his co-workers for their dedication to Blues–America’s indigenous musical art form.

I’m looking at the poster for the 69 blues festival. It was produced by my firm, Walrus Enterprises–three architecture students looking for some beer money. The poster’s designer was Joe Valerio who has gone on to be something of a famous architect.

The guitar player on the poster was derived from a photo of Buddy Guy.

paul durfee oberst